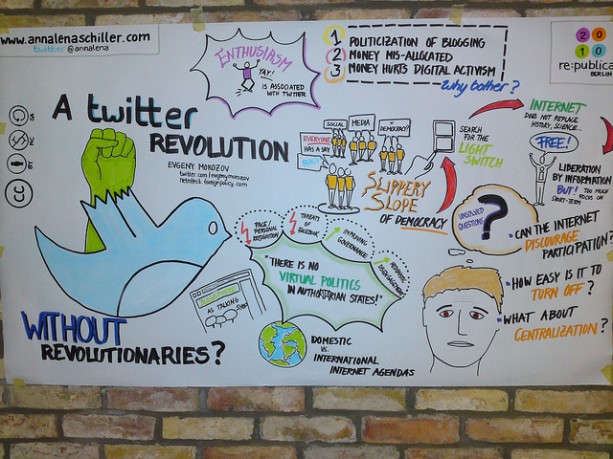

During the protests in Iran in 2009, Internet idealists saw the possibility for peaceful, Twitter-based regime change in oppressive societies. But Evgeny Morozov argues in his book, The Net Delusion, that the reality is that social media can be used to oppress as well as rebel. In advance of Morozov’s appearance at Zócalo on February 16th, we asked scholars in the field whether what happened recently in Tunisia and Egypt was thanks to the Internet or in spite of it.

Social Media Helped–Not a Lot, But Still a Little

Has the Arab world begun to rise up because of the Internet? No. The Internet hasn’t caused the Arab uprisings, it has served as a catalyst for long-standing protest movements. Furthermore, we should remember that in most Arab countries, broadband capacity is still very limited. In Egypt, for example, a forthcoming study by the World Association of Newspapers shows that in a country of 80 million, there are 82 million cell phones. But only 18 million people have Internet accounts, and only one million have broadband.

The celebrated Egyptian blogosphere and Twitter communities are far smaller. Experts estimate that there are some 160,000 bloggers (most of them males between the ages of 20 and 30, working from Internet cafes). The fuzzy number for Egyptians on Twitter appears to be under 15,000 and 30,000 (and is further blurred by the number of Egyptians who tweet from outside the country).

Egyptians have been protesting the Mubarak regime for years, long before the arrival of the Internet, and the seeds of the 2011 protests were planted in the 6 April 2008 movement, launched by textile workers protesting high food prices.

To be sure, digital media have become powerful catalysts. In 2008, a group of students and young urban professionals took up the cause of the striking workers and disseminated it on Facebook, blogs, and SMS. This online activity allowed a working-class movement to garner middle-class support. It helped local strikes spread across the country, and converted national tensions into an international crisis. Digital media also allowed us to follow real-time updates from young, educated people, who take a keen interest in issues such as human rights abuses by brutal Egyptian police forces.

But the international community should not forget that the vast majority of Egyptians are left out of this conversation – starting with the 30 percent of the population that is illiterate.This doesn’t mean the Egyptian population opposes the values of the Facebook generation. It simply means that, due to decades of censorship of the legacy media, and the skewed demographics of the online community – we don’t know yet.

Anne Nelson teaches at Columbia’s School of International and Public Affairs and consults, tweets, and blogs at PBS MediaShift on international media issues.

—————————————————————————————————————

The Web is Changing the Rules

Internet access and use is a game changer in the Arab world-and ultimately in any authoritarian context. It gives power and voice to “the people,” broadly defined. Since the Internet is spreading in the Middle East and Africa faster than anywhere else, it is fast becoming powerful enough to overthrow dictators. I am encouraged to see that technological tools can be used to better the human race in non-violent, gender- and class-inclusive, democratic and populist ways

We are still waiting to see if the revolutions bring about the ideals of equality and opportunity that galvanized the people of Egypt and Tunisia. In the mean time, though, old orders are crumbling in the face of youth armed with mobile phones, digital cameras, Facebook pages, and tweets. As one Tahrir protester poignantly stated,”Husni Mubarak and Omar Suliman don’t know how to SMS, and neither uses email. Both of them don’t speak our language.”

New media, a new language of freedom and collective responsibility, and new politics go hand in hand. Internet use changes culture, social values, consciousness, activism, and politics. Social media enable the collection of grievances, organization on the cheap, and processes of social leveling. The Internet provides a fuel for collective action. It opens new spaces for opposition, risk taking, and opportunities for using one’s voice. The end results can be revolutionary, as Egypt and Tunisia show.

Will these revolutions be exported? This question has heads of state throughout the region throwing money at their publics to appease them (Bahrain and Kuwait) or making small changes in order to avoid an Egypt-like eruption (Jordan, Syria and Algeria). As we all know, shutting down the Internet doesn’t help anything. The changes enabled by the technology are not easily erased from people’s habits and expectations.

There’s a messages that’s been circulating lately on cell phones in Egypt and beyond. It reads, “From Tahrir Square to our brothers in fellow countries…is there anyone who has a president bothering them?” Such words suggest that the revolutions in Tunisia and Egypt are just the beginning.

Deborah Wheeler teaches Political Science and Middle East Studies at the US Naval Academy. She is author of The Internet in the Middle East: Global Expectations and Local Imaginations in Kuwait (Albany: SUNY Press, 2006).

—————————————————————————————————————

There’s No Substitute for People

From reports in the news, you might think that Facebook or Twitter simply delivered freedom to Tunisia and Egypt through the Internet’s tubes. The pronouncements of a “Twitter revolution” sprang up yet again as Tunisians ousted Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in January of 2010, and news outlets continue to focus on the role of a single Facebook group in toppling the Egyptian regime.

Of course, it’s far more complex than that: Though these tools were certainly helpful–even instrumental–in allowing for the quick and easy spread of information in both countries, the fact is that they are just that: tools. And, often, the implication behind proclamations of social media revolutions is that, if only everyone had access to such tools, they’d all be able to topple their regimes.

Such oversimplifications ignore the very real issues of Internet access (and lack thereof), as well as the reality of the blood, sweat, and hours that go into an uprising. Tools can help, but they can’t topple a regime. Only people can.

Jillian C. York is a blogger, activist, and researcher whose work focuses on Internet censorship and social media, with an emphasis on the Arab world.

—————————————————————————————————————

Fuel, But Not the Spark

Egyptians have a long history of toppling problematic regimes dating back to 570 B.C., when soldiers, angry over the preferential treatment of Greek mercenaries, overthrew the pharaoh Apries. To a student of history, the February 11, 2011, ouster of former President Hosni Mubarak seems like just another rebellion in a society that traditionally forces regime change when the masses feel aggrieved.

But unlike those that preceded the February 11 upheaval, commentators are suggesting that the recent uprising was the product of social media – dubbing it the “Facebook Revolution.” But are Facebook and similar sites really the cause?

Revolutions are like fires in that something must ignite them. In the overthrows of Apries and Mubarak, the cause was the same as in nearly all popular uprisings throughout history: the mistreatment of the rioters. It is the sense of injustice or exploitation – not social media – that ignites a revolution.

This, however, doesn’t mean social media don’t have an important role to play. In fact, sites like Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube facilitate political uprisings in four ways:

1. Social media help potential activists learn of events abroad, which in turn can inspire similar behavior at home. Just look at how events in Egypt have encouraged this week’s demonstrations in Iran, Bahrain, and Algeria, just to name a few.

2. Social media facilitate the organization and coordination of protests. This was best seen in Cairo, where Twitter and Facebook were used to alert fellow citizens of meet-up points for rallies.

3. Social media serve as outlets where the oppressed can express their dissent – to fellow citizens as well as to foreign sympathizers. In extraordinary circumstances, hand-held technologies capture and circulate images and videos that – like the June 2009 shooting of Neda Agha-Soltan during the Green Uprising in Iran – create martyrs for a cause and shame regimes in a way that might never be lived down.

4. Social media give protesters courage and hope from the virtual solidarity and encouragement they receive from sympathizers through such outlets. Anyone logged in to Twitter last week likely saw “#Jan 25” superimposed on a plethora of profile pictures, reminding those in the streets of Egypt that they had the support of millions worldwide.

To return to our analogy, social media are akin to accelerants that fuel a fire. While they may not ignite a revolution, they can help assure it burns for some time to come.

Louis Klarevas is a member of the clinical faculty at New York University’s Center for Global Affairs, where he also serves as the coordinator of the graduate transnational security program.

*Photo courtesy of kaffeeringe.

Send A Letter To the Editors