It was a rare indulgence for me that Sunday evening back in early 1984. It was January 22nd, and for once I wasn’t halfway across campus in the basement of the engineering school, the place we computer science majors at Yale (a new, demanding, and hardly fashionable major) affectionately called “the cave.” I was back at Ezra Stiles College watching football, drinking beer, and wondering if my roommate Pat might have a heart attack. His hometown Washington Redskins were favored to win the Super Bowl that evening against the Raiders of whatever city they happened to be representing that year.

If you were a fan of “Lost,” and you recall the underground bunker where Locke and the others had to go punch mysterious codes into old computers to stay alive, you can pretty much picture what our “cave” was like. I spent countless hours and sleepless nights there hunched over terminals connected to mainframes on campus and beyond via shoebox-like modems. With the flick of a few switches and the entry of cryptic words and numbers, you could connect to room-sized computers at universities and other institutions around the world through the ARPANET (which, at the time, we didn’t know was the creation of a congressman from Tennessee named Al Gore). I was in awe of all this leveraged computing power, felt empowered and validated by it, and I’d get such a kick out of sending my inconsequential programming assignments to the massive CRAY computers at NASA or Los Alamos to be processed.

Things weren’t looking good for Joe Theisman and the ’skins in the third quarter when the network cut to a commercial break. Back in 1984, people didn’t watch the Super Bowl for the commercials–it was all about the football. All of a sudden this intense, film-like ad comes on. It was the first commercial of the night that stopped our conversation cold. You know the one I’m talking about: an athletic woman running toward a screen with the image of a “big brother” disseminating propaganda to the assembled, glum masses. The athlete throws a sledgehammer into the screen followed by the announcement that Apple would be introducing the Macintosh two days later, with the promise that 1984 wouldn’t be like “1984.” The ad was a clear dig at IBM, which had introduced their drab and unfriendly “Personal Computer” three years earlier. But it was also a dig, dare I say it, at our cave and our view of computing.

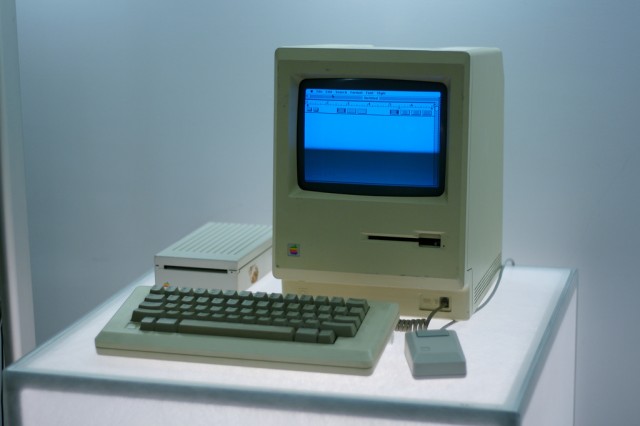

A few days later, Apple started taking student orders for Macintoshes. Eager to see the machine that had been announced during the Super Bow-l-and about which I had heard rumors about on electronic bulletin boards for several weeks–I went to the Yale Co-op to check out the quirky beige box with the cute screen. I immediately fell in love. The Mac reminded me of the state-of-the-art Apollo workstations in our CS lab with technology developed by Xerox PARC. It had a similar GUI (Graphic User Interface) where you’d “click” and “drag” stuff around to icons with a device in your hand. The Mac also had black lettering on a light background (cleverly conceived of as your “desktop”) that was easier on the eye than the harsh fluorescent green (or orange) font on the dauntingly black void typical of most terminals and the IBM PC at the time.

That first Mac came with two applications (MacPaint and MacWrite), a 3.5″ disk drive that was atypical in the age of the larger floppy drives and disks, and, get this, 128k RAM memory. My iPhone today, which cost about an eighth of what that Mac cost (and a lot less if we adjusted today’s dollars to 1984 dollars), is some 67,000 times more powerful in terms of raw computing capacity. That first Mac came with the relatively slow, but powerful, 8Mhz Motorola 68000 CPU. The retail price was not cheap: $2,495 before the student discount (that’s about $5,400 in 2011 dollars). Many of my fellow nerds in the cave immediately panned this new machine, dismissing it as “a toy,” but some of us, like me, were enthralled. The machine’s compact design, down to the “mouse” that liberated the cursor, was intoxicating, and there was a lot of untapped power in that Motorola chip.

From the very start, there was that seductive marketing wooing us, suggesting computing could be cool in ways that even our liberal arts classmates might get: the cheeky Orwellian ad; the whimsical smiley face when you signed off the computer; the overall emphasis on design; the sense of belonging to a community of individuals who didn’t see themselves merely as an accessory to some anonymous mainframe.

IBM had also tried to personalize computing, but that was a bit like expecting Soviet art festivals to amount to a counterculture. It seemed odd then, but perfectly natural in retrospect, that from the very early days this expensive computer came with an Apple sticker. The quirky touch I most appreciated was that the signatures of the Macintosh development team were engraved in the plastic on the inside of each machine. No one could see the signatures, but, if you were in the know, you knew they were there.

I will confess that I didn’t place my order immediately. I had heard rumors that the 128k version would be followed in a few months by … drum roll, please … a 512k version. Quadruple the memory! Even then, at the creation, one was already confronted not only with the marketing genius and design flourishes that would make Steve Jobs a towering figure in American life but also with the should-I-buy-now-or-await-the-upgraded-version dilemma. Word in CS circles was that the “Fat Mac” would be released soon after the initial product. And sure enough, I placed my pre-order for the Mac 512k only a few months later, on the first day Apple was accepting orders at the Co-op. Apple had unwittingly created the first generation of gadget owners who felt cheated because their hot new device had been outclassed within a few months.

I received my “Fat Mac” on the day it was released in September of 1984. I also got my hands on programming software and the esoteric Motorola 68000 Development System, giving me access to the deepest recesses of the software and the ability to tap the power of the CPU to develop my own programs. I also got a modem from the CS department, which turned my Mac into my very own terminal to the outside world, liberating me from the cave. I was online in 1984 from my bedroom. That was almost unheard of in those days.

I did a lot with that Mac (turns out the MacPaint software was there to impress girls). Most ambitiously, I developed the first FORTRAN interpreter for the Macintosh (we used to say the full word more) as my senior year independent project. This was a formidable undertaking, whose pointlessness can hardly be overstated. I mean, I had the future in my room and I nearly killed myself to empower Mac to run an obscure and soon-to-be-obsolete programming language. What was I thinking? Our college facebook was always at arms’ length to occupy my time waiting for the computer to finish tasks! Why didn’t I think of simply uploading it online?!

Soon after graduation, I quit programming and moved on to other professional and personal pursuits, but I still like to think of myself as having been present at the creation, in a small way. And who knows–if FORTRAN had been the wave of the future, maybe I’d now be running my own foundation dedicated to the betterment of humanity.

It’s astonishing to see how far we’ve come in the 27 years since that Super Bowl commercial and the arrival of that charismatic beige machine. I am tempted to say that this smartphone age of ubiquitous connectivity and super-computing power (by 1984 standards) would have been unimaginable to anyone watching that Super Bowl in 1984, but then maybe it was imaginable in broad strokes to Steve Jobs. So many of the elements were already in place then: his drive to humanize technology; his marketing genius; his sense of whimsy; his emphasis on communication.

Even the cultish nature of Apple was already in evidence. I still have the inaugural issue of MacWorld magazine, published around the time the Mac was launched, which is largely dedicated to advertisements congratulating Jobs and his team for revolutionizing technology. The cover shows a confident Steve Jobs hovering over his new creation. Well, maybe not too confident–he was still wearing a gray suit in those days.

Steve Jobs helped push technology, and all of us as individuals, out of the cave. That’s why I am not surprised that millions are mourning his passing this week, and why I’ve found myself reflecting on 1984. Mine–and Steve’s.

Roberto Martinez, the brother of Zócalo’s less tech-savvy editorial director, lives in Dallas and is the senior vice president of marketing and strategy for a Texas-based financial services company. He carries the iPhone and iPad and continues to grapple with the buy-now-or-wait-for-cooler-version dilemma when it comes to all things Apple.

*Photo courtesy of Marcin Wichary.

Send A Letter To the Editors