Campaigning for president in a continent-spanning nation of more than 300 million people is a daunting task, but it’s made all the more difficult by the profound differences between our cultural regions. What sells to partisan voters in New Hampshire may scare off South Carolinians from the very same party. The political certainties of Mississippi or East Texas are the stuff of controversy in Maine or Western Oregon. Most swing states swing precisely because they are riven by deep cultural fractures, as in Ohio, Pennsylvania, or Missouri. The candidates may be fighting for victory in the Electoral College, but they often succeed or fail based on their ability to build coalitions between American cultural regions whose boundaries rarely respect state lines and whose ideals, values, and political preferences are often in conflict.

We fought a civil war over profound regional differences in the 1860s and a cultural war in the 1960s, with striking geographic similarities. In the year I was born, then-Republican strategist Kevin Phillips used regional cultural geography to create a roadmap (a literal one) that Richard Nixon and the GOP used to take control of the federal government. We’re all familiar with the “red state, blue state” maps of recent presidential elections. What’s even more fascinating is to look at the “red county, blue county” maps and see many of the same geographic divides pop up in the elections of 1860, 1912, 2000, 2004, and 2008, even as the parties have swapped their geographical affiliations.

Nonetheless, regionalism remains underappreciated and underestimated. As I argue in my new book, American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America, our country has been fractured on geographic lines since the days of Jamestown and Plymouth. The original clusters of colonies were founded by people with profound differences in ethnography, religious affiliation, political values, and societal goals, and throughout the colonial period and beyond they looked at each other as competitors and sometimes as enemies, even going so far as to fight on opposite sides of major conflicts like the English Civil War or, indeed, the American Revolution.

In troubled times like these, Americans often seek solace in the works of the Founding Fathers, hoping that if we returned to their ideals, if we understood and followed their intent, we would restore our civic strength and social cohesion. But this effort is frustrated by the simple fact that the men who came together to confront a common enemy in 1775 and to craft an enduring alliance in 1789 were not in fact our country’s founders, but rather the founders’ great- or great-great, or great-great-great- grandchildren. And those real founders–early 17th-century Puritans and Dutch West India Company officials, mid-17th-century English aristocrats, late 17th-century West Indian slave lords, and so on–didn’t create an America; they created several Americas. When their descendants gathered at the First Continental Congress or the Constitutional Convention, they didn’t share an intent, but rather several intents, one for each of their countries, as they themselves referred to the bits of geography they represented. The federated entity they created–the United States–has, to this day, been riven by internal contradictions and disagreements over the meaning of American identity and experience, of words like freedom and liberty, and over the implications of the founding documents themselves. We’ve never been a nation-state like Japan or Sweden. We’re an awkward alliance of disparate nations, some of which have less in common with one another than any two states of the European Union.

For generations, these Euro-American regional cultures developed in remarkable isolation from one another, consolidating their own cherished principles and fundamental values, and expanding across the eastern half of the continent in nearly exclusive settlement bands (and, in the case of New Spain, north into parts of what is now the American West). Some championed individualism, others utopian social reform. Some believed themselves guided by divine purpose; others championed freedom of conscience and inquiry. Some embraced an Anglo-Protestant identity; others ethnic and religious pluralism. Some valued equality and democratic participation; others deference to a traditional aristocratic order modeled on the slave states of classical antiquity. In the 19th century, what I have identified as the original nine nations of North America spawned two “second generation” nations in the western half of the continent, and in the 21st century we are seeing the reemergence of a pre-colonial culture on the political stage: that of the First Nations of the far north in Alaska, Canada, and, especially, Greenland.

There isn’t the space to adequately describe all 11 nations here (you’ll need to read the book for that), but for the past two centuries, there has been a consistent struggle for power–a cold (and sometimes hot) war between the two superpowers: the Deep South and the Greater New England cultural space, which I call Yankeedom. Lacking the population to dominate the federation by themselves, each has sought to establish and maintain coalitions strong enough to seize control of the federal government and, perhaps, the direction of the American experiment.

Since the days of the early Puritans, Yankeedom has sought the betterment of the “common good” of the community through public agency, social engineering, and, whenever necessary, individual self-denial. The Puritans came on an “errand to the wilderness” to build what they saw as a more perfect society–a fundamentally utopian project–and their descendants consciously sought to expand this New Zion to the upper Midwest (in the early 19th century), the central and northern Pacific coast (in the mid-19th century) and even the former Confederacy at the point of a gun (during Reconstruction–an abject failure). Yankee culture respects intellectual achievement, expects broad citizen participation in politics, and, more than any of its rivals, sees government as an extension of the citizenry itself. Since the 1840s it has had a reliable partner in the Left Coast, a Chile-shaped nation hugging the Pacific from Monterey to Juneau, which shares its utopian ethic. In the 20th century, the Dutch-founded region in and around the Big Apple–a global commercial trading society that values freedom of conscience and inquiry–joined this “northern alliance.”

Opposing this Yankee coalition is a Dixie bloc led by the Deep South, a nation founded in the lowlands around Charleston, South Carolina by Barbados slave lords, a West Indies slave state modeled on the slaveholding republics of Ancient Greece and Rome. Controlled by a fabulously wealthy oligarchy, it maintained a formal racial caste system maintained by state and state-sanctioned violence right up into living memory. It has always had an authoritarian ethos, and demonstrated strong resistance to broad citizen participation in government, which was traditionally viewed as the preserve of oligarchs. For three centuries the Deep South’s leaders have sought to maintain a low-tax, low-wage economy unfettered by meddlesome federal powers (the resented meddling has taken many forms over the generations, from trade tariffs to civil rights legislation). Supported by its (now) weaker satellite, the Mid-Atlantic Tidewater country, the Deep South tried to secede from the union in the 1860s. Now backed by two sprawling, individualistic nations-Greater Appalachia and the Far (read: interior) West–it has managed to dominate the federal government in recent decades. Its epic battles against the northern alliance are won or lost based on the ability to woo the non-aligned “swing nations,” the Spanish Borderlands and, especially, the (Quaker-founded) Midlands.

Recognizing this state of affairs is enormously helpful in analyzing the challenges and prospects of the presidential candidates. At this writing, the great political question is whom the Republicans should nominate to challenge President Barack Obama in 2012, and the choice appears to be between Mitt Romney and whichever social conservative (Michele Bachman, Rick Perry, Herman Cain, and so on) is anointed the flavor of the month among party activists. A “nations”-based analysis confirms the conventional wisdom that Romney would have a significantly greater chance of winning a general election, even if he is a less exciting prospect for primary voters in the Deep South.

Perry’s problem is that he is profoundly polarizing in regional cultural terms, and might not travel well. He is strong in the regions already guaranteed to vote for whoever stands against Obama. The Texas governor is a Dixie bloc candidate extraordinaire, an Appalachian conservative committed to the Deep Southern agenda: to slash taxes, social spending, labor rights, and government regulation; to support the erosion of barriers between church and state; and to suppress gay rights, reproductive rights, and the ability of ordinary people to seek legal redress against the powerful.

If Perry is the nominee, Republicans can forget the Upper Great Lakes states, New Hampshire, and the Pacific Northwest. (New Hampshire Republicans tell pollsters they prefer Romney 41-8, their Michigan counterparts, 40-17.) Perry’s brand of conservatism falls flat in Yankeedom and will fire up Democratic turnout on the Left Coast. (Mitt Romney, by contrast, could conceivably peel off Wisconsin and New Hampshire in the general election.) Perry would also be unlikely to capitalize on Obama’s unpopularity in that vital “swing region,” the Midlands, a culture that eschews extremes of left and right. Perry has a 51-percent disapproval rating in Midland-controlled Iowa, and he polls behind Obama in Pennsylvania precisely because he’s alienated the Midlanders of Pittsburgh and the Delaware Valley. This also puts him at risk in two other swing states, Ohio and Missouri, which might otherwise go Republican. Imagine instead how many more states would be in play if a moderate Republican governor like Chris Christie, hailing from a traditionally blue state, had decided to take on Obama–assuming his cultural regional differences hadn’t turned off too many GOP primary voters in the Deep South and elsewhere.

Social conservative candidates fare better against Romney in the Deep South. But all of this gains Republicans few additional electoral votes: these regions are strongly opposed to Obama and would vote for whomever is nominated to run against him. Someone like Perry might be slightly more competitive in Florida, but he is a liability in the other swing states–a poor trade-off in the Electoral College.

As President Obama begins to campaign across our fractured federation, he should be keeping his fingers crossed that Mr. Perry or one of the similarly divisive Tea Party candidates winds up with the GOP nomination. It would make the daunting task before him considerably less daunting.

Colin Woodard is the author of American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of America. He will speak at a Zócalo/Center for Social Cohesion event in Washington, DC on October 17.

Buy the book: Skylight, Amazon, Powell’s

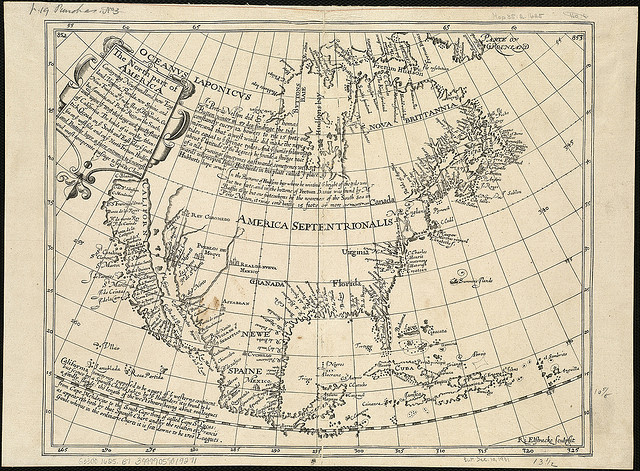

*Photo courtesy of Norman B. Leventhal Map Center at the BPL.

Send A Letter To the Editors