Today’s conservative Republicans are often depicted as mostly men from the middle of the country. But women were among the earliest conservative activists on the suburban political landscape of Los Angeles after World War II. Their fervor would make the Republicans who gathered in Tampa for the national convention seem tame by comparison. But some of the places where they met–non-profit, volunteer-run bookstores–bear a surprising resemblance to the coffeehouses that gave birth to the new left.

Conservatism took root among the white, educated women who landed in the San Gabriel and San Fernando Valleys with their professional or corporate spouses after World War II. As these men and women’s fortunes rose with the postwar economic boom, many of them connected with the new conservative intellectuals on the coasts who denounced welfare liberalism. They excitedly read the National Review after its release in 1955 and listened to the radio addresses of the libertarian Christian preacher, James Fifield, who spun individualist ideals from the Bible during broadcasts from his downtown Los Angeles ministry.

Though not necessarily more passionate about their conservatism than the men, the excitement of the women of the ’50s came from how they viewed their role as community volunteers. These were women who could not serenely carry on with their everyday business because they believed communists were taking over the country before their very eyes–and it was their duty to help stop them. They began opening bookstores in their communities to teach the public, as they saw it, about how the big government and political “subversives” threatened freedom. The metropolitan region sprouted, by my count, 36 different conservative bookstores to disseminate the volumes of literature that these women had been circulating amongst themselves for years.

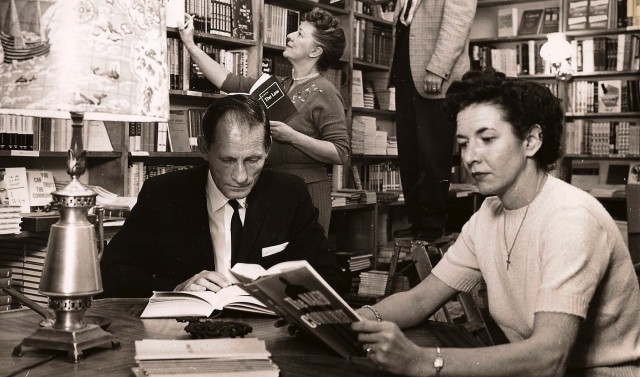

Poor Richard’s Book Shop, the first, opened its doors at Hollywood and Vine in May 1960. Operating out of a family-run insurance agency, owners Frank and Florence Ranuzzi built a thriving walk-in and mail-order business. Frank ran the agency while Florence ran the non-profit bookstore. Shelves displayed thin paperback guides to communist history, philosophy, and tactics that walked readers through Marx, Hegel, Lenin, Chinese “brainwashing” techniques, and front groups. Ex-spy memoirs proved so popular as to constitute their own genre. Shoppers could choose from titles like Witness by the famous Alger Hiss antagonist Whittaker Chambers and The Big Decision by Matt Cvetic, who infiltrated a Pittsburgh unit of the Communist Party for the FBI.

Poor Richard’s became a political headquarters for the conservative movement, where the Ranuzzis and their friends produced bumper stickers, printed leaflets, and organized protests. Florence Ranuzzi also presided over lively discussions, which, according to her daughter, gave Poor Richard’s the feeling of a conservative “salon.” Men, women, and teenagers would drop in on Saturdays to sit around a big captain’s table and hear Ranuzzi give talks about communism.

There were other bookstore hotbeds. The South Pasadena Americanism Center opened shortly after Poor Richard’s in 1961. Founder Jane Crosby, a leader of the John Birch Society, envisioned the non-profit store as an outlet for the knowledge and materials that she and her friends had been acquiring through their studies of communism over the years. “We have been lending books back and forth between ourselves so we can become informed,” she explained to the Los Angeles Herald Express. “Now we want to come out from behind the bushes and get right out on the main street.”

Crosby and her team of housewives developed the atmosphere of the South Pasadena Americanism Center with care. Shelves of books stood amidst a robust patriotic décor of gold-toned walls and curtains dotted with liberty bells. The visitor could scan literature by category: Education, American Principles, Economics, United Nations, Communist Techniques–making it easy to locate Barry Goldwater’s The Conscience of a Conservative, J. Edgar Hoover’s Masters of Deceit, or Verna M. Hall’s Christian History of the Constitution. The John Birch Society’s American Opinion Magazine could be purchased as well. The furniture encouraged customers to do more than buy. With a big round oak table and comfortable rocking chair, the Americanism Center made it easy for shoppers to sit, read, and talk with salespeople about the materials.

Just as coffeehouses and student unions served as the public spaces of the new left, patriotic bookstores became nerve centers of the emerging Los Angeles right. Although men and women shopped in these stores, women ran most of these establishments. To many curious Southern Californians who wandered in, these proprietors represented their most direct human encounters with the conservative movement. The women volunteers not only stocked the shelves and worked the register but also made reading suggestions and answered questions both in person and over the phone. Their friendly demeanor contrasted sharply with the tone represented in much of the material they sold.

The Americanism Center, like Poor Richard’s, functioned as a political community center. People could register to vote there, and the events calendar announced lectures, luncheons, workshops, and meetings. On the counter sat petitions for patrons to sign and postings of groups and political candidates in need of phone-callers and envelope-stuffers. Conservatives in Los Angeles also came to rely on the South Pasadena store as a support center and hotline–all they had to do was dial through to the red, white, and blue phone at SY.9-1776.

In 1962, one concerned woman called because she realized that a tennis ball she purchased at Bullock’s was made in Czechoslovakia. The Americanism Center volunteer she spoke with assisted her by sending along a copy of the Shopper’s Guide to Communist Imports. Another caller reported that her conservative views had recently cost her a job she had held for 17 years. She was desperate for work and hoping that someone at the center might help find an employer friendlier to her political outlook. In 1963, the popular anti-communist lecturer Florence Fowler Lyons called from Presbyterian Hospital, where an ambulance had taken her. She just needed to talk … after collapsing with grief upon the death of her cat.

What happened to the bookstores and these women? They failed to last into the 1970s, primarily for the same reason that most non-profits and “movement” bookstores do–they rely on the time, energy, and money of a small group of people who cannot sustain the energy and momentum. Times also changed. When the immediate threat of communism lost its potency, the housewives moved on to other causes.

But the L.A. women and their bookstores left a mark. Today, conservative booksellers, driven more by ideology than profits, thrive online. And Republicans now produce candidates–like Sarah Palin and Michele Bachmann–who resemble the old booksellers in perspective, style–and fervor.

Buy the book: Skylight, Amazon, Powell’s.

Michelle Nickerson is assistant professor of history at Loyola University, Chicago and author of Mothers of Conservatism: Women and the Postwar Right, from which this article is adapted. She speaks to the Huntington-USC Institute on California & the West at the Huntington Library on September 7 at 12 p.m.

*Photo courtesy of Michelle Nickerson.

Send A Letter To the Editors