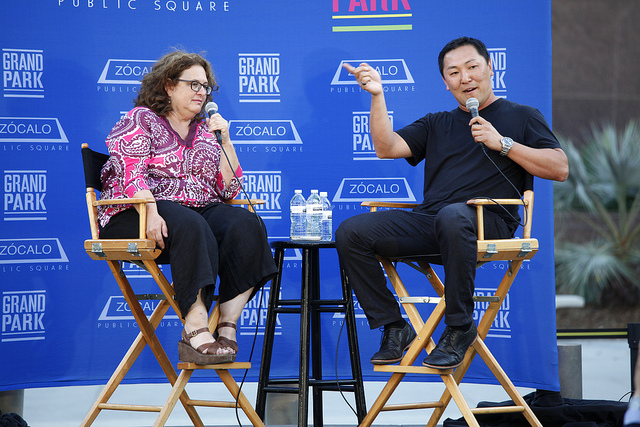

Sang Yoon, chef and owner of the Father’s Office and Lukshon restaurants, sat down with KCRW Good Food host Evan Kleiman to talk about entrepreneurship, inspiration, burgers, and, of course, ketchup (or rather the lack thereof at his Santa Monica and Culver City gastropubs) at a Grand Park event in partnership with the Music Center.

Kleiman introduced Yoon by explaining how, in 2000, the former executive chef at Michael’s in Santa Monica came to open a restaurant famous for burgers and beer. But she wanted him to start at the beginning.

Yoon was born in Seoul. When, Kleiman asked, did he leave South Korea?

“I was the tender age of one, so I don’t have a lot of fond memories of Korea,” said Yoon. An only child, he traveled to L.A. with his parents by way of Tehran (his father was friends with the shah) and Paris (his mother worked for Chanel for many years). “I grew up in Brentwood, and I went to school in Santa Monica,” said Yoon. “Westside kid, don’t hate me for that!”

Yoon said his first entrepreneurial experience was “probably making fake IDs in high school.” He added, “I think the statute of limitations is up, so I can admit it now.” In college, Yoon started a small company with friends making snowboards just as the sport was taking off; three years later, they sold it to Salomon.

So how did food come into the picture?

Yoon said his parents weren’t culinary influences (“My mom cooks horribly”). They had loftier goals for him. “Back then there was no such thing as a famous chef–except Chef Boyardee,” he said. When he told his parents he wanted to become a chef, “They said, ‘You want to be the help?’”

But they agreed to let him go to culinary school in San Francisco after he graduated from high school a year early. His stint there was short but memorable. He was thrown out “for being a total dick”; he rebelled against the prescribed uniform, a pleated paper hat that was to be worn in all classes, even those in a classroom with no kitchen.

Yoon landed next at the Culinary Institute of America in Hyde Park, New York, enrolling only after ascertaining that they didn’t require students to wear a hat in class. But his tenure there likewise ended early, this time after some late-night mischief at the expense of a classmate’s ice sculpture of Paris. “I re-carved the Eiffel Tower into a very phallic” structure, he said, and “added some balls.”

After working on a farm and in high-end kitchens in Europe, Yoon returned to Los Angeles. He recalled how, in the late 1990s, he and his colleagues lamented L.A.’s lack of a fine dining culture–which Yoon said he associated with the city’s not having a theater culture. Yoon was working at Michael’s, but he wanted to create a different type of restaurant.

Inspired by the casual enotecas, tapas bars, and brasseries of Europe, Yoon took over Father’s Office, a bar where he had been a regular for many years. He cleaned it up, added a small kitchen, refined the tap system, and, in 2000, opened L.A.’s first gastropub.

Father’s Office had long been one of the few places in L.A. that had a good selection of small-producer beers, and Yoon wanted to continue the tradition while serving food that reflected what he called “casual Europe.”

He had no intention of serving a burger, but a friend of his insisted. So Yoon drew on an unlikely source of data: an informal journal he’d kept of all the burgers he had eaten. Yoon compiled his notes into a spreadsheet, breaking down the parts–bun, sauce, meat–and trying to find a commonality among his favorite versions of the burger.

“I found I liked bacon,” he said.

He also borrowed the flavors of French onion soup (beef, bread, gruyere cheese, and sweet onions) and of dry-aged beef served at Peter Luger Steakhouse in New York. Father’s Office, too, dry-ages its beef. “It’s a step that nobody else takes. It’s an incredibly costly, labor-intensive piece of the pie that makes the beef the star of the show,” he said. This is why he didn’t want the burger to be condiment-laden.

“You know where this conversation is going,” said Kleiman: to ketchup. Why doesn’t Yoon have it on the menu?

“There was no intention not to serve ketchup,” he said. “I simply forgot it.” But “one guy ruined it for everyone” by giving Yoon a hard time the first night the restaurant was open. He decided if one guy was going to “be a dick about it,” Yoon wasn’t going to serve ketchup to anybody.

At the bottom of Yoon’s menu at Father’s Office is a warning: “No substitutions, modifications, alterations, or deletions.” Kleiman said that the same line now graces “every menu of a certain generation of chefs.” The directive wasn’t driven by ego but by necessity, Yoon said. His business was too small to accommodate special requests. “Sorry,” he told the crowd.

As the evening came to a close, Kleiman asked Yoon to talk about his newer project, Lukshon, which opened in Culver City in 2011, and his test kitchen. Lukshon’s name is a play on the Yiddish word for noodles–a strange choice for a Korean Angeleno chef. But, said Kleiman, Yoon “had a secret bubbe.”

When Yoon was a child, his parents met an older Jewish woman who became a grandmother to Yoon. She was his first culinary influence–he puts veal shin bones in all his stock because she put beef bones in all her dishes. She also taught him an important lesson about Chinese restaurants.

“My grandma Rose only ate pork in Chinese restaurants,” he said. And when he asked her why she felt comfortable breaking the rules of a Kosher diet, she told him, “‘God can’t see us in here.’” He grew up thinking Chinese restaurants were “safe havens from deities”–and he still believes that they’re a place where you can get away with a great deal of mischief.

So what has Yoon been up to at his test kitchen, and what’s next?

Yoon said that he equates his test kitchen–which isn’t attached to a restaurant–with a musician’s recording studio. It’s a place where he can “jam,” and experiment with his many modernist kitchen gadgets. He invented a special sink that freezes and recirculates water, helping save the large amounts of money restaurants spend on ice and energy to cool down hot ingredients.

Yoon also revealed that he has a top-secret project in the works. “I can share that it is top secret,” he said, and that “it involves really famous people.” But his lips were sealed.

In the question-and-answer session, an audience member asked if, now that Yoon has made it in the industry, he feels he’s less innovative. Yoon said no, because his nature is to overthink things and also because the pressures are different now. He has 180 people working for him, and he’s thinking more about the business side when it comes to innovation. “You’ve got to find a way to do what you do better,” he said. “I have to make their jobs easier.”

Watch full video here.

See more photos here.

Read Angelenos’ ideas for the city’s next great restaurant chain here.

*Photos by Aaron Salcido.

Send A Letter To the Editors