About a month ago, I received a letter from Mitt Romney’s campaign addressing me as “one of America’s most prominent Republicans.” This was news to me. I can assure you that if I were one of America’s most prominent Republicans, I’d be among the first to know.

But even if the Romney campaign’s algorithms were flawed, Romney’s path to the Republican nomination, and his late resurgence in the polls, turned on his ability to determine what people want to be told. Targeting specific voters, even in a country of more than 300 million people, is essential for candidates eager to form the appearance of a personal connection in an impersonal era.

At least they seem to think so. But how much do we really know about how and why victors win elections? These are the questions Sasha Issenberg sets out to answer in his new, thoroughly reported book, The Victory Lab: The Secret Science of Winning Campaigns. They are also questions without wholly satisfactory answers. The trivial answer—by getting the most votes—is the only one that is entirely accurate, and it is not very helpful. Issenberg chronicles the efforts of a small group of political insiders to figure out two things: the most efficient ways to boost their side’s turnout, and the best ways to get swing voters to support their guy. These two goals are pursued through two methodologies that constitute the bread and butter of what Issenberg calls the new empiricism: the use of randomized field experiments to measure efficacy of campaign tactics, and the integration of demographic data from commercial databases with polling information to “microtarget” voters.

“The crucial divide,” Issenberg writes, “is not between Democrats and Republicans, or the establishment and outsiders, but between these new empiricists and the old guard.”

Hal Malchow, a Democratic consultant with a background in direct mail, is a pivotal figure in Issenberg’s story. Malchow is an old-school operative who pioneered empirical techniques before they were in vogue. The old guard, in Issenberg’s characterization, relied on political instinct. The empiricists, of whatever ideological stripe, rely on field experiments to learn what convinces the electorate to turn out for their candidates. The book opens with Malchow, and others, cajoling people into voting by sending them letters reminding them they had voted in the past—an approach Malchow found, via randomized experiment, to be more cost-effective per vote than other types of letters.

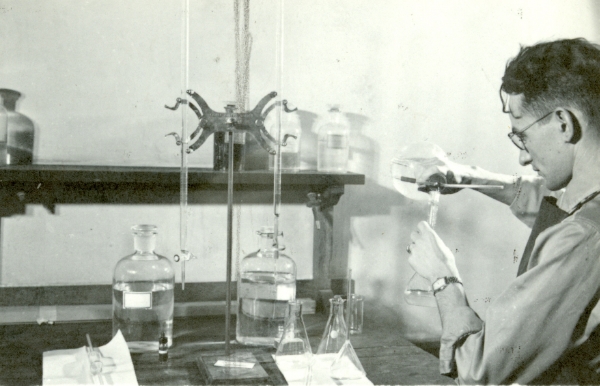

Issenberg traces the history of these empirical efforts back to Harold Gosnell, a University of Chicago political scientist who started writing in the 1920s. Issenberg quotes a review of Gosnell’s first book, which asserted that it would soon be possible to “draw conclusions about elections ‘with all the assurance of a chemist proving the quality of a new paint-remover.’” It is the thesis of Issenberg’s book that, though the time was not ripe in 1924, political operatives today have the assurance of chemists.

But this raises two distinct questions. The first is whether the broad class of randomized statistical techniques that Issenberg describes is as effective as its proponents claim. The second is whether aspirants to high political office widely believe them to be effective.

The answer to the first question is that they are not all that effective; but this is, in a way, secondary. If candidates—and the small army of moneymen whose backing is vital to run for high office—believe that quantitative optimization is the key to victory, then only candidates who embrace such techniques will even have a shot. The necessity of the technique then becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. What does this do to our stock of aspiring politicians? This is a second-order effect, not itself amenable to randomized empirical study, and as such Issenberg does not address it in the book. But it is a vital question.

In an essay in The New York Times Magazine, Matt Bai expresses bafflement as to why Barack Obama has failed to, in the president’s words, “tell a story to the American people.” In Slate, Issenberg, in a sort of postscript to his book, explains how Obama outdid Romney in adopting empirical techniques. Neither Bai nor Issenberg makes the connection that Obama’s failure to construct a narrative and his success in use of randomized experiments are intimately linked. Storytelling is too complicated to feel your way randomly around, constantly gauging the response of your audience. As E.B. White once said, “there are a thousand ways to express even the simplest idea … [writers] are constantly faced with too many choices and must make too many decisions.”

A democratic leader has two conflicting tasks: shaping the will of the people and reflecting that will. This paradoxical tension is as old as democracy. More precise, granular information about the public’s opinion shifts that balance. The capacity of a leader to bend the public’s will to his own is one measure of greatness. But it is easier to build up a good model of what people think than a model of what will cause them to change their minds.

In principle, a candidate could use the techniques of the new empiricists to figure out how to best convince voters of something they did not already think—say that higher gasoline prices make economic sense, or that climate change should be a pressing concern. There is nothing inherent in random sampling to prevent its being so used. But in practice, as Issenberg narrates, the techniques are used to convince voters that the candidate already agrees with them, rather than to convince voters to agree with the candidate. Issenberg tells the story of John Kerry’s 2004 victory in the Iowa caucuses as a cautionary tale against neglecting the lessons of data. Howard Dean, who had the early lead in Iowa, lost to Kerry, in Issenberg’s telling, because the Kerry campaign successfully used Iowa as a “petri dish” of tactical optimization. Obama’s strategists wanted to excite voters like Dean did but target them like Kerry did. Issenberg does not consider that though the petri dish might have helped win Kerry Iowa, it also helped lose him the nation, providing the kernel to which George Bush’s charges of flip-flopping could accrete.

Ken Strasma, who worked for both Kerry and Obama, is one of the book’s heroes. “Strasma wanted to create a model that would help Obama’s advisers decide which topics they should use when communicating with its targets,” Issenberg writes. When a mathematical model begins to stand in for moral and intellectual principle, it affects the precarious balance between the President as incarnation of the general will, and the President as a leader.

One needn’t posit a fantastical past of noble Founding Fathers, above the fray (political infighting having been as alive and well in the 1790s as it is today), to take seriously the idea that contemporary empirical techniques make it harder to take a stand on unpopular issues. (Say, for instance, the closing of the extrajudicial prison on Guantanamo Bay.) The one outstanding virtue of a statesman, Hannah Arendt wrote, lies “in being able to communicate between the citizens and their opinions so that the commonness of this world becomes apparent.” However much Issenberg’s new empiricists may claim for themselves a sort of non-ideological methodological rigor, the nature of their work skews the politician towards the timid posture. The appearance of bravery is always easier to sell than bravery itself.

The great irony of Issenberg’s book is that it is far from clear that many of the tactics he describes are as effective as they are made out to be. He mentions this in passing, quoting one of Rick Perry’s number-men, who is questioning the claim that television advertisements have only a transient effect: “The real weakness of the study is it’s a single ad, and you’re extrapolating from that … you could make an argument that OK, there’s a diminution of effects, but that’s just because it’s not a very memorable ad.” This is but one of many examples in the book that fall prey to “overfitting” of data—even if a statistical model accurately accounts for a series of existing observations, that doesn’t mean it will accurately predict the future, or be correct as a causal model, as Nate Silver explains in his recent The Signal and the Noise, which can usefully be read as a companion to Issenberg’s book.

Issenberg concludes with Malchow wondering whether his get-out-the vote letters were so effective not because of what they said, but because of their packaging. “Malchow had spent a quarter century living off the mail, but not until his revelatory steakhouse dinner with Gerber did he give much thought to envelopes,” Issenberg wrote. It turns out that the appearance of the letters—plain and official-looking, a contrast to the slick flyers of Malchow’s past—may have played a bigger role than his phraseology.

As Arie Kopelman, one of Nixon’s ad-men in the 1968 campaign, told the journalist Joe McGuiness, “If the advertising is too slick it’s not then the communication of the man but the communication of the communication.” Both Romney and Obama have fallen victim to this trap in the course of their campaigns. Much has been made in the punditocracy of the renewed importance of the ground game—getting out the vote on Election Day. To take the football analogy a bit further, a team’s ground game will only be effective if it does, at least occasionally, go for the deep pass to the wide receiver. Otherwise, it’ll just be an impasse of blockers and pass-rushers, entwined at the line of scrimmage, with no forward progress. Call it gridironlock.

Send A Letter To the Editors