The story here starts 22 years ago. December, almost Christmas, 1989. I was 5 years old, but my age did not prevent me from hearing death’s roar—the death of democratic martyrs followed in short order by the death of the tyrant. It was death promising freedom after a half century of national captivity, dependence, imprisonment, and servitude. In the West, the crumbling of the Iron Curtain was talked about as the “end of history.” In Romania, it felt like the start.

But, for all the initial euphoria, the ensuing post-Communist decades, with their ups and downs, became a tale of political science in the making, a case study in freedom, democracy, corruption, and the importance of legacy. Americans overdramatizing the dysfunction of their democracy should pause to consider that in some parts of the world, the struggle to consolidate freedom remains existential and ongoing.

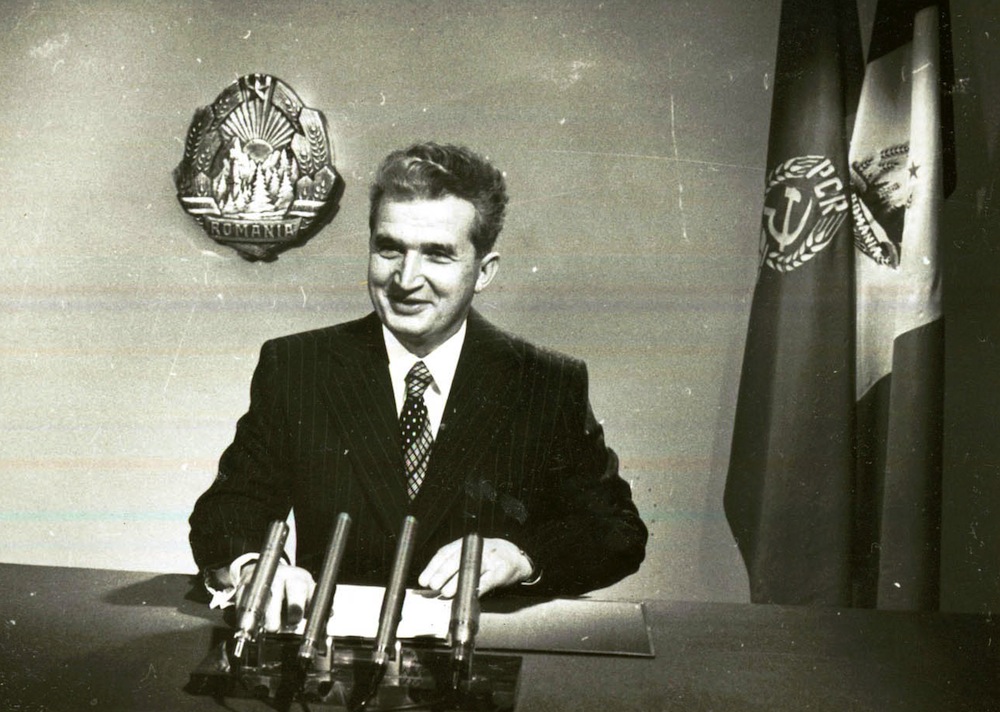

In the immediate aftermath of our Revolution, the only one to spill significant amounts of blood to overthrow Communism, Romanians joked that Poles took a decade from the founding of Solidarity until they overthrew their regime, Hungarians took 10 months to get rid of Kadar, Czechs took 10 days to organize the Velvet Revolution, while we Romanians took a mere 10 hours to dispose of Ceaușescu. In reality, though, change rarely comes overnight. And if it does come overnight, many things remain unfinished.

This is a recurring theme of revolutions. Any sort of immediate, violent change means tearing apart identities and reconfiguring the status quo—at least cosmetically—but too often the change is hijacked by the old guard. A large share of Romania’s political elite was part of the ancien régime, a ruling class shaped by a totalitarian understanding of power. These leaders have a poor appreciation of parliamentary representation, a feeble capacity for cohabitation with other viewpoints, a lack of consideration for citizenship, a weakness for populist demagoguery, and a dangerous tendency to personalize all power dynamics. As Daniel Barbu, one of our most prominent political scientists, wrote almost 15 years ago, “in Romania political parties rule, but they do not govern.”

Romanians lived for more than half a century under an ideology of men who believed they were gods who had achieved the revolution of the proletariat. After the fall of Communism in 1989, Romanians transitioned from one illusion to another. They embraced democracy as an ideal, but not as a practice and reality. And the reality of democracy is all about practice. People had been brought in with an illusion. And when the illusion faded, they found themselves so out of the game that they had no means to address it.

As I reflect on the past two decades, what strikes me most is the plummeting enthusiasm for political participation. The first free elections were held in 1990 and in 1992. The voter turnout then was almost 80 percent. This summer, in 2012, it was under 50 percent. In the years between, disappointment had followed disappointment. In 1990, we elected Ion Iliescu, a political figure who emerged from the events in December 1989 as a savior who also exuded a pragmatic know-how. Then we voted him out in 1996, had second thoughts, and reluctantly voted him back in 2000.

In 2004, Traian Băsescu, the one-time mayor of Bucharest, appeared as a salvation. He was popular as mayor and modern in his outlook. Once voted in leadership, however, Băsescu treated all state structures as personal fiefdoms. He cunningly eluded constitutional provisions and brought to power his cronies, regardless of qualification. His daughter, Elena Băsescu, was put forward as a candidate for European elections, despite a lack of any political experience. Worse, she won. Democracy, it turns out, can only be as good as its cast of characters, and in Romania’s case the self-appointed cast was itself a breach of democratic ideals.

Băsescu’s popularity dropped but he won re-election in 2009 with a slim majority of 50.33 percent of the votes. Members of the opposition, which had led in polls leading up to the vote, cried foul, but the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe certified that the election was held generally in line with OSCE commitments. Then, in January 2012, for the first time in Romania’s recent history, people took to the streets in order to claim their rights. The Economist called it Romania’s “winter of discontent.” Nothing remarkable happened, however. After two weeks of protests with few results, people got tired of protesting.

Two decades into our democratic experiment, we should by now have seen a maturation of our political elites and electorate, a refinement of our dialogue, a new wisdom in making choices, an improvement in our strategic thinking, and maybe more than anything an affirmation of professionalism. Sadly, what characterizes Romania’s present political scene is the opposite of the above. What we see is incompetence, patronage, and demagoguery. We are left with no good role models, no healthy civic culture to build upon.

As a political scientist student eager to examine, explain, and try to predict political events, I was once excited about democracy. Now I feel the need to get out of my profession. Political journalism here means getting mixed up in a dirty game. There’s no respect for the substantive merits of ideas and policies. Writing against an idea, policy or action is considered to be writing against someone. Therefore, the skilled minds of my generation search for alternatives in any other fields. They get into big corporations, they start small NGOs, they turn to creative industries, or eventually they leave the country in search of Eldorado.

Americans recently fretted over division leading up to a so-called fiscal cliff, but at least they fretted. Romania is on the verge of going over the indifference cliff. Even as Romanians take pride in being members of the European Union—again, pretending a label can serve as elixir—our flawed democracy keeps Romania far removed from Europe’s core elites, stigmatizing the capable and qualified people here, as if we are all complicit in an experiment gone awry. People are on the verge of giving up politics.

However, apathy is not a good scenario; certainly, it is no way to honor the martyrs of 1989. Withdrawing from politics—that is, ceasing to be interested in the affairs of the state—is itself anti-democratic. It means giving up all things concerning the polis. The majority of Romanians are not guilty of that, at least not yet. But we will be if don’t soon reclaim ownership of our future.

Send A Letter To the Editors