“My goal in life is to provide evidence for the great transitions in evolution,” announced University of Chicago paleontologist Neil Shubin, author of The Universe Within: Discovering the Common History of Rocks, Planets, and People, to a standing-room-only crowd at the Petersen Automotive Museum. For six years, Shubin searched for a fossil that would show how fish became land-living creatures—amphibians.

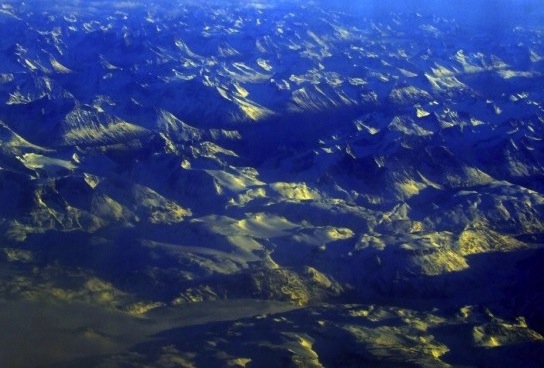

The first step for a paleontologist looking for a certain type of fossil is to find a new place to hunt for it. Using what he called “the paleontology playbook,” Shubin looked for a place with three things: rocks of the right age (in this case, about 375 million years old); rocks of the right type (that preserve fossils and that are where this sort of creature lived); and rocks that are on the earth’s surface. Eventually, up in the Canadian Arctic—one of the most northern patches of land in the world—Shubin and his colleague, Ted Daeschler, discovered the fossil of a creature intermediate between life on land and life in water: a flat-headed fish with fins, tiktaalik roseae.

So what can this part-fish, part-amphibian teach us about humans? “Every time you bend your wrist or your neck you can thank tiktaalik and its cousins,” said Shubin. Fossils like tiktaalik show us powerful connections between human life and life on the rest of the planet—as well as the history of the universe. Every gene of our body, said Shubin, contains over 13 billion years of history—and there’s evidence for that in fossils, in DNA, and in embryos.

The atoms that make up our bodies were generated as part of the aftereffects of the Big Bang. We know, said Shubin, that the elements that make our body, from smallest to largest, were present in other parts of the universe before they came together as humans. When we die, they will become part of other parts of the universe.

“What are our ties to the solar system that are inside our body?” he asked. “Some of them are truly fundamental to our biology.”

One example is our innate 24-hour clock. Even when we are disconnected from light and darkness, humans—as experiments have shown—stay on a 24-hour clock, as do flies, hamsters, and other mammals. In fact, “every cell of our bodies contains a clock inside it,” said Shubin. “Inside of us lie over 2 trillion clocks, each of which is tuned to a 24-hour cycle.” These clocks drive our health, our mood, and our susceptibility to disease. They also reveal our connections to other animals on our planet, and to the solar system—our planet’s rotation.

The origins of human life, too, can be traced back to the solar system. Looking at the full fossil record, you can see that in certain periods of time, many species die out virtually simultaneously around the world. One of these cataclysms took place 65 million years ago, when the dinosaurs died out. One explanation for this mass extinction is that an asteroid hit the planet. And although small mammals existed before this cataclysm took place, it’s only after the dinosaurs died out that there were larger mammals—or larger mammals that left any evidence. “If it wasn’t for an asteroid, our lineage wouldn’t even be here,” said Shubin. Mammals might just be tiny animals living at the feet of dinosaurs.

So was it inevitable that human beings came to exist on Earth?

We could prove this definitively if we were to meet space aliens who looked just like us, with a fossil record just like ours, said Shubin. But short of that, we have to measure probability and chance against the predictability of evolution. A species survives a cataclysm thanks to completely random features, so there’s a degree of chance involved. Yet similar features crop up in all types of plants and animals, said Shubin—different species exhibit the same solution to different problems. This parallel evolution, he said, may be the manifestation of something important in our genes, which are shared between worms, flies, and people.

We know, thanks to these shared genes, that our species isn’t as distinctive as we once thought it was—just as science has taught us that our planet isn’t so special as to be at the center of the universe. We know that we originated thanks to a combination of chance and necessity, predictability and contingency. And we know, too, he said, that we’re connected to the rocks on our planet, to the rest of our solar system, and to the universe beyond.

In the question-and-answer session, audience members pressed Shubin on how special he thinks homo sapiens are, on what our future evolution holds, and why the culture wars between science and religion refuse to end.

Shubin said that studies are showing—and he believes will continue to show—that animals have a larger degree of consciousness than we give them credit for. And he thinks that our level of consciousness has increased thanks to a positive feedback loop—one in which consciousness spreads more consciousness.

Are we still evolving? “The answer is absolutely yes,” said Shubin, and the proof lies in changing mortality and fecundity among different groups. He noted that socioeconomic and cultural factors affect how evolution is happening to us. Shubin believes that in a thousand years, “the primary drivers of human performance will not be Darwinian selection but our ideas and our culture.”

Given all we know about science, history, fossils, and evolution, asked one audience member, how is science still challenged by religious ideology? The crowd laughed as Shubin paused to consider the question, which he said he thinks “is a really important question of our age.” Shubin thinks that the disconnect between known science and what we believe is a result of science phobia as much as religious dogma. “I think they exist in our society in equal measure,” he said.

Shubin said that he works to combat people’s fear of science by telling stories of discovery—human stories of people taking chances and making mistakes, persisting over time and getting lucky. A story of discovery transforms the conversation: making it accessible, human, and harder to argue with.

Send A Letter To the Editors