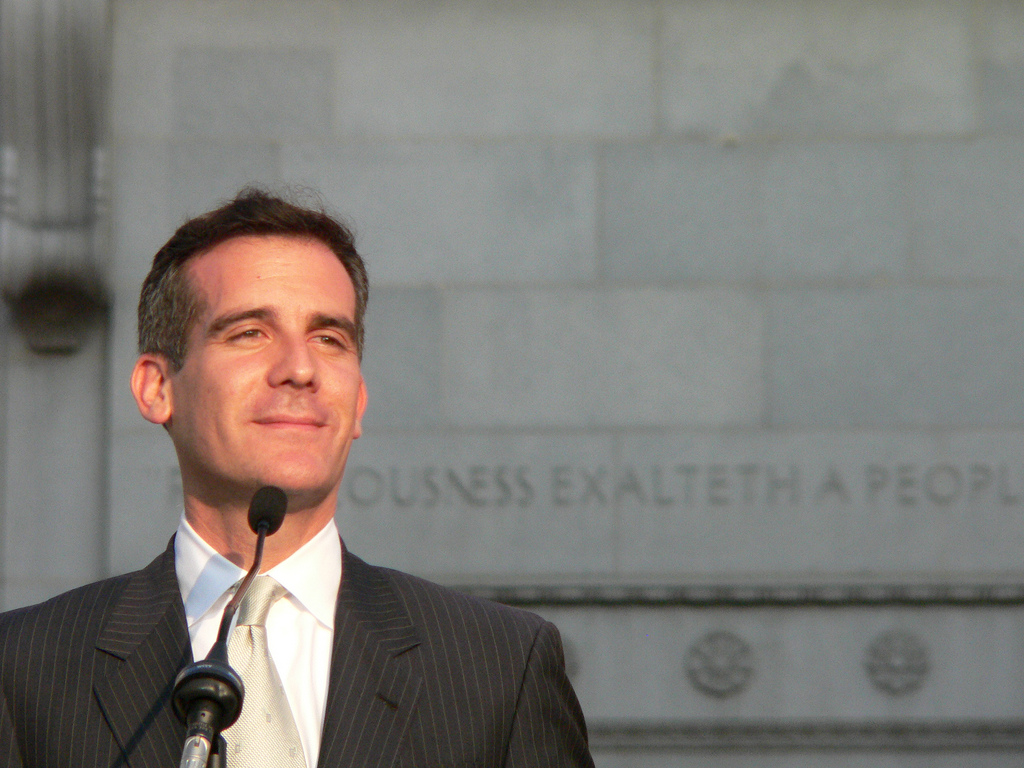

On May 22, 2013, the day after Los Angeles voters elected Eric Garcetti mayor of Los Angeles, something astonishing happened: He became Jewish.

No, he didn’t suddenly convert. Garcetti never hid that he contained multitudes. His father, Gil Garcetti, is Mexican-American with Spanish, American Indian, and Italian ancestry. His mother, Sukey Roth, is the granddaughter of Russian Jewish immigrants.

In this town, that makes Garcetti a pretty common blend of many ethno-religious flavors—an L.A. Smoothie. But by Jewish law, which is matrilineal, Garcetti is a full-on Jew. To those of us who tracked Garcetti’s career, none of this is new. But to that ever-shrinking demographic known as the L.A. city voter, it seems to have come as a surprise. “Most people didn’t know that during the election,” Councilman Paul Koretz told a reporter on election night. “I tried to get that word out.”

Part of the fault is in our own preconceptions. The most obvious way we assess a candidate’s identity is by his or her name and face. Yaroslavsky and Villaraigosa and Wesson are easy—Jew, Latino, black. But Jews are also a religion and a culture, and the big trend in Jewish life is just how much the old phrase “Funny, you don’t look Jewish” reflects the new reality of Ethiopian Jews, “Jewtino” conversos, and Chinese-born adoptees, not to mention Persian and Middle Eastern Jews. The garden-variety white Ashkenazic Jew is becoming as hard to find as a great Westside deli.

How many times this year did I have to remind people that Jan Perry, the black 9th District councilwoman who also ran for mayor, is also Jewish? When we sat together on a panel at the Autry National Museum in May, I inelegantly described Perry as “not a typical Jew.” She took offense. “Maybe not to you,” she said. Point taken.

But the other reason people assumed Garcetti isn’t Jewish is that as a candidate he spoke little about that side of his heritage.

“I always felt myself to be Jewish and Latino very comfortably,” Garcetti told Jewish Journal columnist Bill Boyarsky in a rare candidate profile that delved into his religious identity. “Weekends were both filled with bowls of menudo and lots of bagels.”

Garcetti told Boyarsky that growing up he celebrated Passover and Chanukah, and attended Jewish camp. In college he connected more seriously to his Judaism. As a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford University from 1993 to 1996, Garcetti befriended the charismatic rabbi Shmuley Boteach, who would go on to write the book Kosher Sex, minister to Michael Jackson, and star in his own reality show, Shalom in the Home.

While “Rabbi Shmuley” veers politically right—he ran unsuccessfully for a Republican Congress seat in New Jersey last year—the two remain close. It was Boteach who wrote a column in the Jewish Journal on Garcetti’s behalf just prior to the election, calling him “pleasant, humble, wise, sincere, and serious.”

Garcetti’s religious affiliations, like his political ones, are liberal. He is a member of IKAR, a mid-City congregation with a famously liberal rabbi, Sharon Brous. He attends High Holy Days and occasional Shabbat services—what we in the trade call a twice-a-year Jew. Garcetti’s wife, Amy Wakeland, is not Jewish.

By these measures, Garcetti is like a great many modern American Jews—the offspring of an interfaith couple, intermarried, liberal, and more culturally than religiously Jewish.

Contrast that with two of Garcetti’s opponents in the mayoral race, Perry and Wendy Greuel. Perry, a convert, identifies strongly with her religion. Greuel, Garcetti’s opponent in the runoff, is married to a Jewish man, Dean Schramm. She makes it clear that they are raising their child as a Jew, and people are genuinely surprised —maybe it’s the name— to hear she is not in fact Jewish.

It’s not fair to say Perry and Greuel played the Jewish card harder, if that’s what you do with a Jewish card. It just seemed to come more naturally for them both.

After the election, a small dispute arose among journalists over whether Garcetti was, in fact, the first Jewish mayor of L.A. It turns out that from November 21 to December 5, 1878 a businessman named Bernard Cohn was appointed interim mayor by the city council, the equivalent of a mayor pro tempore, a position Garcetti and other Jews have held. But it’s certain that Garcetti is the first elected Jewish mayor in L.A. history.

Cohn represented what the UCLA historian David Myers called the first phase of Jewish political life in Los Angeles, when, during the city’s pioneer days, Jews faced little prejudice. After 1900, the city’s influx of East Coast and Midwestern WASPs brought with them a dour anti-Semitism that nudged Jews away from the power structure, even as the Jewish population increased from 136 in 1881 to 315,000 in 1951. This second phase was spent in the political wilderness.

The 1953 election of Rosalind Wiener Wyman, a Jewish woman, to the city council heralded the third phase—complete acceptance. The coalition of African-American and Jewish communities that combined to elect Tom Bradley as mayor in 1973 created a liberal Jewish Westside power base that spawned politicians like Zev Yaroslavsky, Howard Berman, Henry Waxman, Joel Wachs, and one of Bradley’s young aides—Wendy Greuel.

Even as L.A.’s Jewish community grew to 600,000, though, Jews never held the highest offices. The last election changed that in a big, sweeping way, bringing into office a Jewish city controller, Ron Galperin; a Jewish city attorney, Michael Feuer; and a Jewish mayor, Garcetti.

Jews have finally reached the top job at a time when the idea of a pure ethnic voting bloc seems as timely as Tammany Hall. It’s not that Jews don’t vote—they do, disproportionately to their numbers. (Past Los Angeles Times exit polls have shown that Jews, who make up just 6 percent of the city population, constitute about 16 percent of the vote.) But if in the past that vote automatically defaulted to the Jewish candidate, that’s no longer the case. The Jewish vote tends to go to the candidate who best articulates and can best deliver on a socially progressive, fiscally prudent, pro- (or at least not anti-) Israel agenda.

Ethnicity alone doesn’t buy you votes or campaign donations—but familiarity and loyalty help loads. That’s why it’s hardly an exaggeration to say that the first Jewish mayor of L.A. might have been a man who was a native of Boyle Heights, who counted a Jewish teacher as his first mentor, and who spent more time in Israel than most Jews: Antonio Villaraigosa. Love him or hate him, the man knew his way around a shul.

The election of Garcetti doesn’t even come with that swell of (often self-congratulatory) Jewish pride that accompanied, say, hearing that Sandy Koufax refused to play on Yom Kippur or that the flash drive was invented in Tel Aviv or that—best of all—Scarlett Johansson is a Member of the Tribe.

Maybe that’s because, in a city that has seen so many Jewish pols and powerbrokers, one more isn’t kvell-worthy. Or perhaps it’s because we want to see how he does before we embrace him.

After all, that early interim Jewish mayor, Bernard Cohn, was a dubious character. He pulled a fast deal on Pío Pico, the last Mexican governor of California, which resulted in Pico spending his final years destitute. Cohn was married to Hulda Myer and had three children with her. But after Cohn died, a Catholic woman came forward and proved she was also his wife and had seven children and a house in Los Angeles Plaza with him.

“Claim them and blame them,” Stephen Sass, the historian of Jewish Los Angeles, once told me was his motto when it came to Jewish politicians who fell short of expectations. But if Garcetti does a great job, you can be sure the Jewish community will be bursting with pride.

Whether you take the position that Garcetti’s being Jewish doesn’t matter, or that it only does if he makes his People proud, there’s a deeper question underlying all of this: What, in a post-modern, post-ethnic age, does it mean to be a Jew?

Does it mean that your faith calls you to behave a certain way, to stand for certain things? Does it mean there are certain values and principles that you are charged to uphold? Is there a Jewish vision of social justice or of environmental and communal stewardship? What does it mean not just to choose to be labeled as a Jew, but to choose to act as one? This, of course, is a question that faces every Jew in the modern age, and it now faces Eric Garcetti, who, on July 1, 2013, became the first Jewish mayor of Los Angeles.

Send A Letter To the Editors