Swept up in the carnival of Super Bowl XLVIII, today’s Broncos and Seahawks can’t be blamed for their myopia. They will inhabit this celebrated moment, but they’ll never know the depth of brotherhood that great teams of early Super Bowl years—like the 1970s Pittsburgh Steelers—shared, and still share.

In this salary-cap era, NFL teams are the result of a transactional opportunism that brings together talented free agents for a few seasons, as if for a gig. The Denver star quarterback, Peyton Manning, and go-to receiver, Wes Welker, are still identified by fans mostly as having played with the Colts and Patriots. Seattle’s star running back, Marshawn Lynch, came in a 2010 trade, and before this season the Seahawks traded for wide receiver Percy Harvin and signed veteran pass rushers Cliff Avril and Michael Bennett as free agents. NFL general managers work their rosters these days like Rubik’s Cubes.

We are unlikely to witness another enduring NFL empire like those 1970s Steelers, who won four Super Bowls in six seasons, launching nine players into the Pro Football Hall of Fame. They were a team in a way that today is no longer possible in the NFL.

Consider this: eight of those Steeler greats—defensive linemen Mean Joe Greene and L.C. Greenwood, quarterback Terry Bradshaw, safety Donnie Shell, receivers Lynn Swann and John Stallworth, and linebackers Jack Lambert and Jack Ham—played a combined 100 seasons in the NFL, and every single one of those seasons was played in a Steeler uniform. In Super Bowl XIV against the Rams in January 1980, not one player on the Steelers’ roster had ever played a down for another NFL team.

The 1970s Steelers knew each other intimately, the women they loved, the cigarettes they smoked, their favorite brands of beer (Lambert: Michelob, always in bottles, never cans).

That closeness created synergy on the field. The Steeler players also shared a love for team owner Art Rooney Sr., aka the Chief. As founder of the Steelers, Rooney had been a lovable loser in the NFL for 40 years. As a horseplayer, though, he rated among the nation’s best, a shrewd gambler with a sixth sense. Rooney was an American archetype, Irish-Catholic and local, up from the streets of Pittsburgh’s north side, his leather-bound prayer book in one hand and the Daily Racing Form in the other.

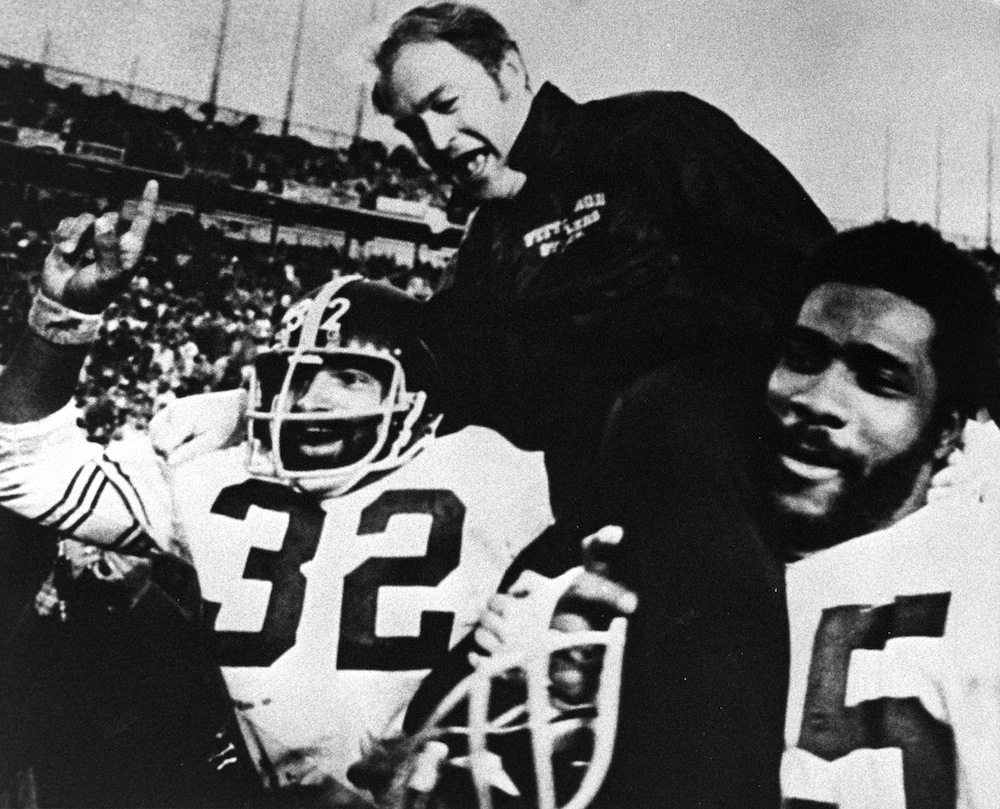

The players wanted to win one for the old man. The defining hour came in January 1975 in the locker room at Tulane Stadium in New Orleans after the Steelers had defeated Minnesota 16-6 to win Super Bowl IX. Linebacker Andy Russell, a defensive captain, called for Rooney, then 73 years old. With his teammates crowded around, Russell presented him with the game ball. “This one’s for the Chief,” Russell said. “It’s a long time coming.”

***

The Steelers’ brotherhood flourished during the ’70s inside their post-game hide-away: the locker room sauna at Three Rivers Stadium, a stadium that exists now only in memory. It was players only. No coaches, no press. Only about seven or eight big men could fit in the sauna comfortably, though sometimes a few more squeezed in. The equipment man turned off the steam and filled a trash can with ice and beer. Players talked about the game just played, needled each other, laughed, and reveled in their moment.

As Bradshaw told me, “The sauna was our escape, and nobody could get to us. That was the most fun we ever had.”

Pro football has its gifts, and costs. The costs often come later, like a bill past-due. A man sees himself much differently in his 20s than in his 50s or 60s. In his 20s, he is invincible. He looks at 50, his father’s world, like a faraway planet. But once a man reaches his 50s, he sees himself with a wisdom and context that the passing decades have provided. He understands that life is short, and values his special friendships more.

In the quiet of night now, the game calls out for payment, and the 1970s Steelers, grandfathers now in their 60s, feel it in their muscles and bones. They all live with some pain, differing by degrees.

Bradshaw suffered at least seven concussions as a Steelers player. In 2011, he struggled to remember names and statistics on the studio set of FOX NFL Sunday. He went to a Southern California clinic to undergo brain scans and diagnostic testing. He said he began taking multiple pills, including power boost and mood boost pills. He also downloaded brain puzzles from the Internet and to help his hand-eye coordination he bought two Ping-Pong tables.

Running back Franco Harris takes blueberries and fish oil each morning to slow brain damage that he believes he and every other NFL player suffered. Reggie Harrison, the Steelers’ special teams kamikaze now known as Kamaal Ali-Salaam-El, says he takes Oxycontin and other medications for head, back, and leg pain, and whisks though his northern Virginia home on a motorized scooter. Running back John (Frenchy) Fuqua needs latches on the doors at home in Detroit because his surgically repaired wrists can’t turn a knob. Greenwood underwent so many back surgeries he lost count, maybe 14 or 15.

“I feel like I’ve been rode hard and put away wet,” Greenwood told me by phone last fall, several days before his final back surgery. He groaned in pain, put the phone down, shifted in his chair, and upon his return apologized. Two weeks later Greenwood died, at 67, due to complications from that surgery.

Twelve Steelers from the days of empire died before 60. The causes of those deaths varied widely, including cancer, heart attacks, and accidents involving a car and a falling tree. Quarterback Joe Gilliam died at 49 from cocaine overdose.

For a time, Mike Webster lived out of his truck, virtually homeless. A Hall of Fame center, Webster played 17 NFL seasons. He retired at nearly 40 and died at 50, and in between lost his money, his marriage and, ultimately, his mind. In 2002 he became the first NFL player diagnosed posthumously with chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), a neurodegenerative brain disease.

“What has the game given me?” said John Banaszak, a defensive lineman for the ’70s Steelers. “It’s given me my teammates … You want to talk about what the game takes away from you? It takes away your teammates.”

***

The enduring Steeler brotherhood reveals itself in different ways. When they are together, often at Pittsburgh-area charity events such as the annual Mel Blount Youth Home celebrity roast fundraiser, you can sense their closeness in the way they embrace, in the stories they tell.

Decades later, Donnie Shell’s children still call Stallworth “Uncle John,” and Stallworth’s children call Shell “Uncle Donnie.”

Two old veterans from the Super Bowl IX team, Russell and center Ray Mansfield, kept a deep friendship until Mansfield’s heart attack in 1996. After their days as teammates, they hiked mountains together in the West, and traveled across the world together. Today, Fuqua and Salaam-El have each other on speed dial. They talk multiple times each week. “Our friendship,” Salaam-El told me, “will see us into the grave.”

Franco Harris has become the social glue of the team, and is so deeply involved in charitable causes that Greene calls him Mister Pittsburgh. When his son, Dok, ran for mayor of Pittsburgh in 2009, some of the 1970s Steelers campaigned for him. He has hosted private dinners on the 25th, 30th, and 40th anniversaries of the Immaculate Reception, Harris’ famous catch to win a 1972 playoff game against the Raiders. He invited Steeler teammates and their wives, and footed the entire bill himself.

Stallworth, the Hall of Fame receiver, earned his master’s degree in business while still playing for the Steelers, then returned home to Huntsville to build an information technology firm in the aerospace industry that he later sold for a reported $69 million. Today, when Stallworth reminisces about the 1970s Steelers, he doesn’t think of big plays or his four Super Bowl rings. He thinks of his teammates and the brotherhood they share. In his fondest dreams, Stallworth would like to bring back all of them—even those who have died—for one more conversation, and he’d like to have that conversation in the sauna at the vanquished Three Rivers Stadium.

Stallworth imagines that they’ll all be there: Mad Dog and Fats, Bradshaw and Webby, Mean Joe, L.C., Rocky, Lambert, and Franco. They’d ask each other questions that men in their 20s and 30s—today’s Broncos and Seahawks, for instance—typically don’t think to ask. What’s going on in your life? What makes you happy these days? What really endures?

Send A Letter To the Editors