My earliest memory is of the evening of March 10, 1933. Our little family was having dinner: father, mother, me, and baby brother Raul, who was sitting in his high chair. Shortly before 6 p.m., the world began to tremble. When the quaking didn’t stop, Mother gathered Raul up, and we all headed for the front door of our house near the corner of 62nd and San Pedro streets in South Los Angeles. We stood on the sidewalk, terrified, looking at the house until we were certain that the ground was again steady under our feet. Neighbors up and down the street were doing the same thing.

The next morning, father, following his ingrained habit, immersed himself in the newspaper stories about the earthquake, sharing his reading with mother. The headline of the Los Angeles Times read: “Scores Perish in Southland Quake.” I was three months short of my third birthday.

My own love affair with Los Angeles newspapers began when I was 8 years old, when Raul and I took turns fetching the Sunday morning paper, the Los Angeles Examiner, off our front lawn. Raul and I loved the color comic strips that served as an outer wrapper for the rest of the bulky paper. The newspapers of the late 1930s and ’40s gave children an enormous variety of funnies to enjoy: Blondie, Popeye, Krazy Kat, Barney Google, Prince Valiant, Terry and the Pirates, and Mutt and Jeff were just a few of them. We peeled off this funnies section and spread their pages out on the living room floor.

Father read the Examiner every day, in later years switching to the Herald-Express. He perused the sports section only when it ran stories about professional boxing and horse racing. I knew about Seabiscuit long before the bestselling book a half century later. Father and I listened together to the radio broadcast of Santa Anita track announcer Joe Hernandez’s call of the 1940 Santa Anita Handicap when the storied thoroughbred defeated a field that included Kayak II. His attention wasn’t just sporting.

Betting on the ponies was extremely popular back then, and his workplace, the Pacific Glass Company, like other companies, had workers who doubled as bookies. The Herald devoted a good deal of space to information that was helpful to readers who handicapped and bet on the horses. This coverage likely explains the change in my father’s newspaper loyalties.

Father’s faithful reading of newspapers distinguished him from most of our relatives, who never read anything. It astounded me that so many of their homes were completely devoid of reading material. But our particular line of Rodriguez men had an especially deep relationship with newspapers. A 1906 photograph of my father’s first birthday showed his father—my grandfather, then a copper miner in Clifton, Arizona—standing next to my father with a folded newspaper in his right hand.

Father was loyal not only to newspapers but also to the glass workers labor union. He was very interested in politics and was a devoted supporter of President Franklin D. Roosevelt. When he listened to FDR’s radio addresses to the nation, the so-called Fireside Chats, I sat on the living room floor listening along with him, thrilling to the sound of the president’s voice. So when, still a child, I began reading the newspapers’ more serious material and its criticisms of this beloved president, the experience shook me. On the first day I read him, the Examiner’s Westbrook Pegler mocked Mrs. Roosevelt and her newspaper column, called “My Day.” I was shocked but learned an early lesson about freedom of the press.

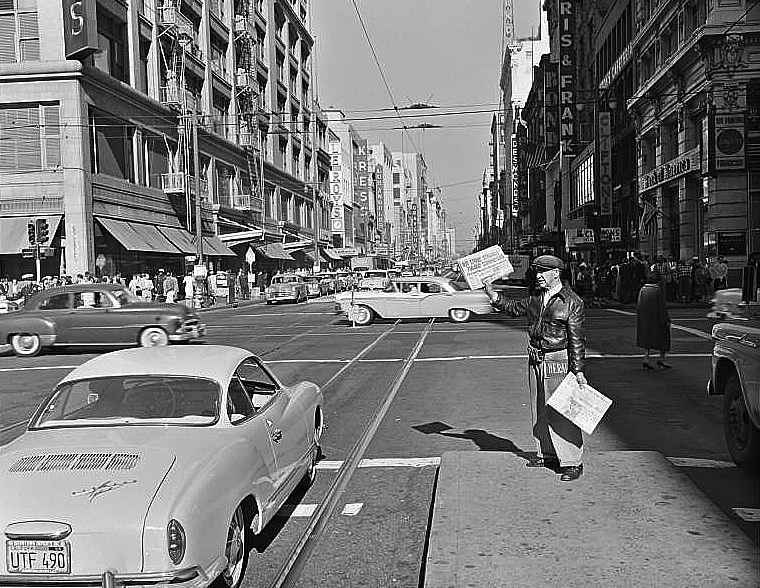

Raul and I sold newspapers for several years, and it became second nature for me to read the headlines as I stood on my corner. There were many headlines and many newspapers then. In addition to the morning Times and Examiner, readers could pick up the Herald-Express or the tabloid Mirror, also an afternoon paper. The Daily News, owned by Manchester Boddy, who would later give his estate—now Descanso Gardens in La Cañada Flintridge—to the county, was the only local daily that supported Roosevelt’s election in 1932 and his subsequent New Deal. (The city’s only Democratic newspaper would cease publication in 1954).

With the onset of World War II, radio came of age, its immediacy an appealing alternative to waiting for the morning or evening paper. The first news of the December 7, 1941, attack on Pearl Harbor was broadcast on the radio. Our family was gathered around the kitchen table that Sunday listening to a musical program when CBS announcer John Daly interrupted with a news flash of the bombing. We listened the next day when President Roosevelt gave the address to Congress in which he declared that a state of war existed between the United States and the Japanese Empire. The Los Angeles Times front-page headline of December 11 was “Axis Declares War on America.”

I followed the news of the war principally by listening to radio broadcasts about the Battle of Britain and the bombing of German cities like Stuttgart, Frankfurt, Hamburg, Dresden, and Berlin. Hearing of news events was fine, but seeing them was even better. The Tower Theater downtown showed only newsreels, many about the war, and I went often to see them. And television was just around the corner.

But it is the headlines I remember—of the fall of German-occupied Rome to the Allies on June 5, 1944, and of the Allied landings on the Normandy coast the following day. The Times’ headline of June 6 consisted of one word: “Invasion!”

Post-war Los Angeles was a far more violent place than today’s Los Angeles, and the newspapers let us know it. On January 17, 1947, the mutilated body of a young woman was found near Leimert Park. The Hearst papers—the Examiner and the Herald-Express—were known for their exploitation of the sensational, and no one did crime stories better than Herald reporter Agness Underwood. Some credit her with popularizing the name Black Dahlia, which was given to the murder victim, Elizabeth Short. In the middle of the case, Underwood was promoted to editor of the Herald’s city desk, becoming the first U.S. woman to hold such a high position at a major metropolitan daily. The Black Dahlia story was astonishingly popular and reached even into the high school I attended. It was rumored that a colleague of mine had been questioned by the police in connection with the crime. (He didn’t do it.)

In 1962 the Herald-Express and the Examiner merged to become the Herald-Examiner. That publication announced the news of its own demise years later on November 2, 1989, with a headline that read, “So Long, Los Angeles.” Despite the swan song, the paper published for several more weeks, running the following on November 11:

The Times pompously declares in its Nov. 2 editorial that the Herald-Examiner folded because ‘the public’s appetite for such reportage is satisfied by lesser television talk shows.’ In the same editorial phrases such as ‘working class tastes’ and ‘entertaining sensationalism of yellow journalism’ are used. This display of arrogant elitism will make the loss of the Herald all the more painful. The Herald considered its readers as peers writing for them and not at all as a didactic parent.

Newspapers were essential for living here. I could not have done without the movie reviews and screening times for a great number of movie houses. (Like Woody Allen, I had to see a movie from the beginning and never deviated from that rule.) I loved the columnists, with whom it was possible to connect personally. A Times reporter named Bill Kiley took a 7 a.m. beginning Spanish class I taught at Valley College, and I ended up being an item in his friend Matt Weinstock’s column; he became my favorite columnist. I also exchanged letters with the legendary L.A. Times columnist Jack Smith, chiding him about pieces he had written about Spain.

It was often said that there was nothing as useless as yesterday’s newspaper. But old papers weren’t entirely useless back then. Thrifty types like me saved the old papers and periodically bundled them up, tied them with twine, and earned pocket change selling them at a salvage center.

In the pre-smog days, Los Angeles backyards had incinerators where old newspapers were often burned along with the rest of the household trash. But after the smog came—but before the arrival of garbage disposals—garbage was gathered in sturdy cans whose contents were emptied every several days into city trucks and hauled away. Old newspapers were very helpful—we lined the garbage can with them. Those who took their politics seriously could put their least favorite politicians’ photos on the bottom of their can.

Send A Letter To the Editors