I’m a Valley girl—I’ve lived in the San Joaquin Valley almost my entire life—and I’ve been a nursing instructor. That combination, according to state jobs statistics, is rare.

There is a serious shortage of nursing instructors in Fresno. It’s one of the greatest shortages of skilled workers in California, which ranks 46th in the nation when it comes to nurses per capita, according to the federal Bureau of Health Professions. The Valley has one of the lowest nurse-to-patient ratios in the United States.

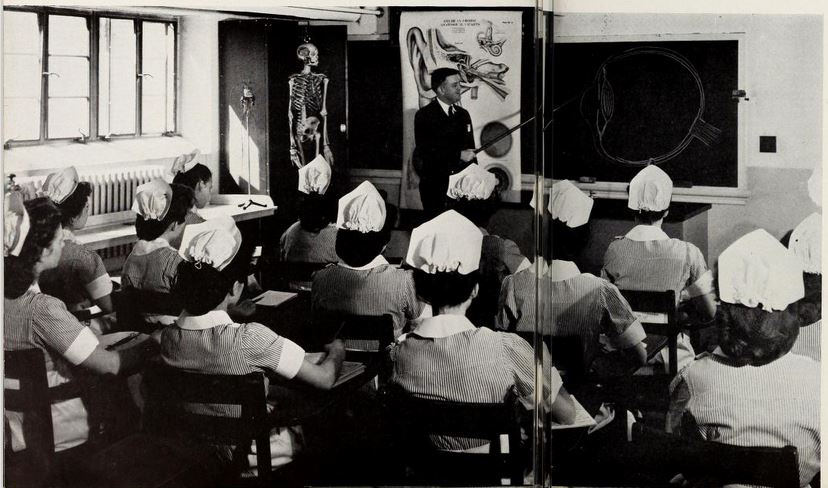

In 2006, I made the switch from chief nurse at the Fresno Heart Hospital to instructor, and taught nursing at San Joaquin Valley College and Fresno Pacific University. Being a nursing instructor doesn’t pay as much as being a nurse administrator—but teaching is exciting. As an instructor, it’s my job to teach students to recognize the abnormal, and establish plans of care for patients. To do this, an instructor needs to stay current with what’s happening in healthcare, which is a field where the only constant is change.

I wanted to be a nurse from the age of 7, when I first admired nurses in their starched white uniforms. When I told my high school counselor in my sophomore year that I wanted to be a nurse, he shook his head and said that, because I was poor and Latino, I should be a secretary. I was undeterred. I even turned down a full scholarship to a business school to become a nurse.

It’s easy to get discouraged when you study nursing. On the first day of class, students are excited, but the reality of the difficulty of the major soon hits home. Each of the major areas of study—medical, surgical, obstetrics, pediatrics, and mental health—has a requirement of many hours of clinical practice.

The pressure is unavoidable when you combine the academic work and those high-stakes clinical hours. If an accountant makes a mistake, it can mean a loss of dollars to the company; if a nurse makes a mistake, it could mean a patient’s life. And there are no shortcuts in nursing. After graduation, aspiring nurses are required to pass a national licensing exam comprised of as many as 250 questions that measures critical thinking in a clinical environment.

Nursing students come from every conceivable background. What they have in common is struggle—many live on a shoestring budget. I’ve had students who slept in their cars because they could not afford to rent an apartment, and their families lived out of town. More than a few are in the “sandwich” generation, caring for both their children and their parents while trying to make it through a nursing program. Many students expect to be able to continue working full-time while going through the nursing program, only to realize that the pace is impossible. When they give up their full-time positions, they are suddenly faced with losing benefits for their families. This can lead to additional stress—and a lack of cooperation or attitude in the structure.

In the years I’ve taught nursing, I’ve come to realize that students have to learn for themselves how they will overcome the barriers to completing a nursing education. I always try to be sensitive—to lend an ear, offer a hug or words of comfort. But I’m also passionate about making sure patients come first. One of the most important lessons I tell students is: If you cannot walk out of a patient’s room knowing that the care you just provided is the same care that you would want for yourself or a member of your family, you need to go back into the room and provide the care again—this time in the correct manner.

The work of a nursing instructor does not fit into a simple 12-hour day, much less an 8-hour shift. There is constant coaching and mentoring that must take place, along with developing and grading tests, reading and correcting papers and care plans, and preparing lectures. It can be challenging to teach nursing, and the pay is often less than what you can make as a registered nurse working a 12-hour shift at a hospital. Most nursing instructors do the work because they love it. Teaching nursing is a calling within a calling.

We desperately need more people with this calling—especially in the San Joaquin Valley. One idea for helping to solve the faculty shortage problem involves hospitals, colleges, and universities working together to create joint appointments for experienced nurses who are interested in teaching. This would allow a nurse to keep his or her clinical job (including salary and benefits) while working as a nursing instructor a few days a week.

More qualified instructors will result in better-educated nurses, and that will be good for everyone. I imagine that someday, I’ll be a patient in a hospital or ambulatory care setting and will recognize the nurse caring for me as a former student. I will smile proudly.

Send A Letter To the Editors