In early 1999, when I was trying to establish myself in Los Angeles as an artist, I supported myself by working at a temp agency that placed me at The Hollywood Reporter’s editorial department. With one other harried temp, I answered a relentless 40-line phone system in a windowless room. We were sequestered away from the executives who sat in private offices with large windows. There wasn’t even time to learn my colleague’s name—only time to ask if she wanted to take lunch first. We took no other breaks. We spent the day yelling out writers’ names while trying to answer random questions like, “Who is Madonna’s agent?”

The only time of the day I enjoyed was the very beginning. Before we turned the phones on, I was sent each morning to the fifth-floor copy room, where I clipped articles out of a stack of morning newspapers from across the country and made copies for all the writers. The copy room had a big north-facing window and took in the twinkly windows of the Hollywood Hills mansions as the sun rose and lit up the day.

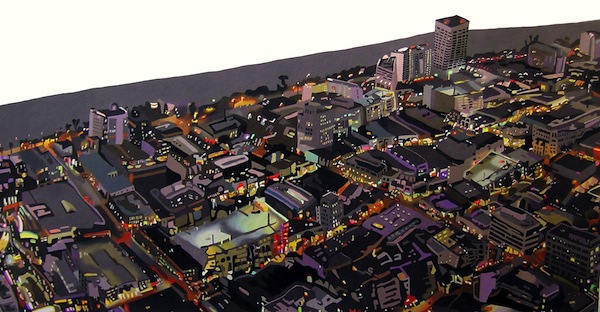

I’m a full-time artist now, and my works are inspired by the kinds of views I originally saw out of The Hollywood Reporter’s copy room. My large-scale, colored pencil drawings depict a cityscape in enough detail to distinguish rooftop air conditioners, streetlights, palm trees, and darkened windows. I don’t use a ruler so there are no straight lines, and I often twist the perspective from looking straight down to an off-kilter, oblique perspective. I draw the city not as it looks but rather as it feels to me.

My work has ended up in public spaces—including law firm lobbies, a baggage claim at LAX, and soon a new station along the L.A. Metro’s expanding Exposition line—because my drawings can feel like fan art for cities. You see the city laid out before you. With all those details, the drawings have a way of slowing people down. You can return to them over and over.

Most of the time, the city that is my template is Los Angeles. I moved here in 1999 from Austin with no car and no job, just a few boxes. I enjoyed discounted rent on half a run-down duplex owned by my future in-laws in what is now the super-fancy-pants part of West Hollywood. I got around by bus, and came to appreciate the low view from the bus windows. I was a veteran of many public transit systems, but until I moved to L.A., I had never seen a homeless man pee into a plastic grocery bag while sitting in his bus seat and then lean over and chuck it out the back door. Unlike San Francisco or New York, where I saw all kinds of people on public transportation, L.A.’s buses contained mostly working poor people, reading the California Driving Manual more often than anything else. Even though I carried a Thomas Guide (the GPS of the late 1990s), I still ended up often walking in the wrong direction as I exited the bus.

But, seeing the city from the copy room, it was laid it out for me in a way I could finally understand. I loved looking at the long boulevards that went on for miles, as well as the minutia: the large and small rooftops, parked cars, people’s backyards, the way the pieces haphazardly, yet perfectly, all fit together.

A few years later, as an art graduate student at Cal State Long Beach, I started experimenting with these high-above views that I came to think of as privileged viewpoints. At the time, I was enjoying them almost every day as a new employee of the Getty—on clear days, I could see east to the Hollywood sign and west to Catalina Island. I wanted to draw every detail because the details were so fun to look at. I figured it wasn’t going to be workable to sit atop a building or perched at the top of the Hollywood sign, so I decided to work from photographs, Google satellite maps, and tourist books. But my work wasn’t a copy of these sources—I filtered this high-up perspective through my memories of experiencing the city from the bus window and as a disoriented pedestrian.

As I drew, each scratch of the pencil, each little swatch of color, signified to me the coming together of people and the passing of time, the building all that stuff. I drew the crowded area around the intersection of Wilshire and Santa Monica boulevards in Beverly Hills and the rows of cement hangars on the Warner Brothers lot in Burbank. Cirrus Gallery in downtown Los Angeles exhibited my drawings and the L.A. Times and Art in America reviewed my work. I came to realize that my drawings were ending up in the more public spaces of privately owned companies. In the summer of 2005, I was commissioned to create three 4-by-6-foot drawings of downtown L.A. for City National Bank’s headquarters. The drawings now hang in the employee cafeteria, which is on one of the upper floors, with large windows looking across the city through a forest of concrete and glass.

I decided to start applying to public art calls so that I could bring this privileged perspective to the masses. I got to create a large-scale mural in Southwest’s terminal at LAX in 2011. The mural—an unending landscape of downtown L.A. printed on a 15-foot-by-60-foot piece of vinyl—was located in the baggage claim area for six months. If there is a happier place than the arrivals gate at an airport, then I haven’t seen it. It gave me a lot of joy to see people greeting each other and posing for pictures in front of my piece, and to give the limo drivers who tirelessly hold up their signs for arriving passengers something to gaze at for long periods of time.

For the last year, I’ve been focusing on my project for the new Expo line station at Sepulveda and Exposition boulevards. With the stipend I received for the project, I finally had enough money to charter a helicopter for the first time and take photos of the city from an amazing new vantage point.

I made three helicopter flights in all. The last one in July was the most memorable, taking me over the 405 at dusk down to Sepulveda and Exposition. We ascended from the airport in Van Nuys in a doorless helicopter, on a weeknight right after a light rainstorm. The 405 was crowded per usual at evening rush hour, and with nothing but air between me and the traffic below, it reminded me how deeply fragile we all are.

When we got to Sepulveda and Exposition, we saw where the 405 connects to the 10, one of the densest parts of Los Angeles. The 1947 song by Freddy Martin (using the pseudonym “Felix Figueroa”) and his orchestra hilariously called the neighborhood a place “where nobody’s dreams come true.” And from ground level it is a little bleak. There’s a cement factory, a lumberyard, and a mail sorting center. But from up in a helicopter, it looked magical as the pink sky turned a darker and darker gray until it was black. Houses and office buildings fanned out in an endless patchwork, and we saw the lights come on, creating an illuminated grid.

Soon there will be condos within walking distance from the Expo line station. It’s easy to imagine other amenities showing up after that. We got the aerial shots we wanted after about 45 minutes, but it was hard to tell the pilot to turn back.

Send A Letter To the Editors