No one can mortify you like your mother. Growing up in northern Mexico with an American mother, I had extra reason to be mortified. Mom was just so—how to put this?—different.

She spoke Spanish with a heavy gringa accent. Worse, she insisted on speaking to all my friends in English, seeing as they were studying it. A typical exchange when my best friend in middle school would come over: “Alfonso, how good to see you. How’re your parents?” “Muy bien, señora. Gracias,” he’d answer sheepishly, while I wanted to slink beneath the table and die.

Speaking of mortification, Mom would insist on coming to school to talk to my teachers, to get a sense of how I was doing, especially if I had gotten into trouble. Parent-teacher conferences, or any other parental involvement in school for that matter, were not a tradition in Chihuahua, so Mom’s engagement resulted in much teasing by my classmates, and much puzzlement from my teachers. That would have been awkward even if she hadn’t tried to press other parents into lobbying my school to embrace some form of sexual education.

* * *

Mom, a native of Dallas, loved Mexico with the passion of the convert. There were no pre-colonial ruins and no colonial cities too remote for us to go check out, no accommodations too gritty. When I was in sixth grade, and Mom discovered that neither my best friend, nor my brother’s, had ever been to Mexico City (most Chihuahua families’ idea of a good vacation was to head north to the United States, not south), she took the four of us on an overnight bus trip to la gran capital, where she indoctrinated these Chihuahua boys in the wonders of their own country. Mom was equally relentless about connecting people, especially her two sons, to her native United States. She taught English, and was constantly advising people on where to go in the U.S.—for vacation, to study, for medical treatment. She was like Google for everyone she knew before Google existed. Remembering her recently, a good friend from those Chihuahua years, one who’d often stick around for dinner, said: “Your mother taught us not to fear the larger world, but to seize it.”

Somehow, Mom managed to pull off having us speak English at home, when our school and the rest of our lives took place in Spanish. She also gave me one of the biggest gifts a parent can give a child—a blue passport with its imposing eagle on the cover. Eager for her kids to know their other country, Mom shipped my brother and me off one summer to a camp on the Pecos River, in New Mexico, only to become annoyed when she discovered that we’d spent most of the time hanging out with the other kids from Mexico. The following year I found myself at a camp in northern Wisconsin, where no other kids hailed from south of Illinois. How she found out about Camp Algonquin, sitting at home in Chihuahua, in that dark time before the Internet, I have no idea.

Mom was resourceful.

* * *

I would love to tell you that there was something particularly poignant or meaningful about my last conversation with my mother in February, but I can’t.

It was mostly about logistics.

I was at the Houston airport, changing planes on the way back from a work trip to Mexico. I was seated at the counter of Johnny Rockets, having ordered a burger. I dialed Mom to tell her the trip was great, and that Sebastian (her 9-year-old grandson) and I would come see her the next day, Sunday afternoon. I asked if she had watched any of the Winter Olympics. She said yes, and we agreed it was all so beautiful. Truth be told, I probably rushed things along to get off the phone as my burger was arriving, and my flight was leaving shortly.

She died the next morning.

Mom had become frustrated with her condition in those last months. She’d spent her life taking care of others, and was ill-equipped to have others take care of her. She was maddeningly resistant to it, in fact. She’d suffered crippling back pain for years, but now her mind was starting to fade away, and that was another thing she couldn’t abide.

We had a rough weekend in January, days after she was formally diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. I was scrambling to get her more help, but in the meantime we were charting new territory as I was suddenly doing things like helping her bathe and putting her to bed. As we were both struggling with our reversed roles one of those evenings, she suddenly looked at me intently and asked me what day of the week it was.

“Saturday,” I said.

She looked disgusted. “So what are you doing wasting it on your mamacita?” she said. “You should be on a date. You need love in your life.”

I moved her into a hotel for a weekend, rather forcefully, while we performed an industrial-strength cleaning of her apartment, and some of my last positive memories of her are centered around her watching Sebastian delightfully splash around the hotel’s indoor pool, and him reading to her, the two alighting each other the way that grandparents and grandkids do, as if sharing a conspiracy or a secret that skips a generation.

* * *

I got over being mortified by Mom once I was away in college; I’d like to think I was appreciative of all she did for me, and maybe showed that appreciation from time to time.

I was then eager to have my mom meet my friends, and even visit my classes. Sitting through Jonathan Spence’s lectures on Modern China was a highlight of my experience at Yale, one enhanced by the fact that Mom was able to sit in once. We also went on a rail trip together through France one spring break, a trip the two of us laughed about for years thereafter. And though I was fairly secure by then in my friendship with Mom, I may not have told all my college friends that I spent that vacation only with her; I was trying to be somewhat cool.

Opening an old box of pictures in her apartment recently, I did a double take at seeing a number of photos of Mom at a Chinese wedding, beaming proudly with bride and groom. It took me a minute to place the groom: Tang Bai! A Chinese grad student I had befriended in college, Tang Bai saw his plans to return to Beijing thwarted by events in Tiananmen Square. A couple years after that, when he confessed to my mother that he would not have any family present at his wedding in Riverside, California, she volunteered to step in as his adopted mom. I didn’t even go. Mom and Tang Bai corresponded for years thereafter, and I got periodic updates about him through her, and vice versa. She was a hub like that—Facebook before Facebook existed.

Mom was the one source of unconditional, loving support throughout my life.

When I announced to my parents late in college that I wanted to get a Ph.D. in Russian history and become an academic, my father stifled a groan, but my mother said: “Isn’t that wonderful? You should pursue what makes you happy.” And not only that, she acquired an interest in Russian history herself, and started reading up on it, and insisted on reading all my papers—which, I can assure you, were not that interesting.

A few years later, when I announced I wanted to segue from law school to journalism—I was now on Plan D or E—my father actually groaned (he was beyond stifling) and my mother said: “Isn’t that wonderful? You should pursue what makes you happy.” Within months of my arrival at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, she wanted to visit the paper, and get to know my colleagues. And once again, she acquired an interest in all things Pittsburgh and media. She read everything and anything I wrote—most of which, I can assure you, was not that interesting. In her apartment, after she died, I found the most extensive archive of all my writings, clippings from the various newspapers where I worked lovingly filed away.

Mom was proud of my accomplishments, which she embellished, as any good mother does. Even more important, she was always forgiving of my many failings.

* * *

In another box I cleared out of her apartment recently I found a journal book, still new and unused, that I gave her a few years back, with my birthday card still stuck inside, in which I’d implored her to write about her early years in Texas. So much of our family’s shared lore when I was growing up was about Dad’s side of the family. We grew up with his mom in the picture, and never met my mom’s parents. I was hoping she could capture on paper some of her reminiscences for posterity.

The reason I never met my Texan grandparents is because they both died on a Valentine’s Day when Mom was in college, some 12 hours apart and from totally different causes. The odds against that merited a short article in the Dallas Morning News. It wasn’t something Mom talked about much, though she oddly couldn’t stop talking about it with the neurologist who diagnosed her with Alzheimer’s in January. He asked a routine question about her parents, and the whole story came pouring out, in excruciating detail—this on a day when Mom had failed to identify the current year, 2014.

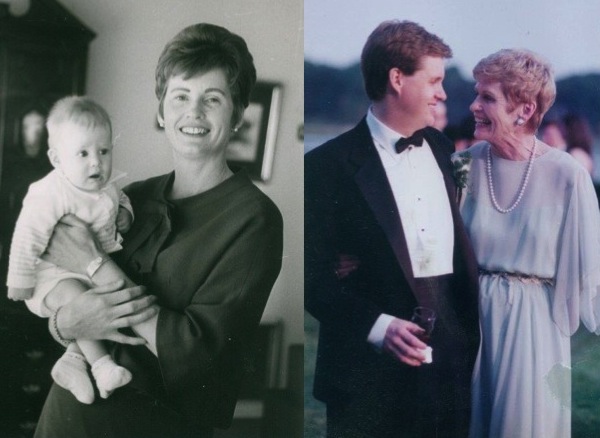

Mom found herself alone in her 60s, unexpectedly divorced after what had been in some ways a very good run. Looking at older pictures pouring out of those boxes in her apartment, I am reminded of a truth you don’t often associate with your own parents: that there was a time when they were loving life, and each other, and basking in their youth. The pictures from that Mad Men era—smoking, cocktails, mini-skirts—give off a glamorous vibe. My parents lived large as my father succeeded at business, in no small part propelled forward by his charming and sharp American wife. In another time and place, Mom could have been a CEO of a major corporation or a politician. She had such intelligence, energy, and boundless organizational talent. But instead she surrendered her teaching career to be the perfect corporate wife in traditional (and sexist) Mexico. Years later, when her marriage died, the rationale for her sacrifice also perished, along with any illusion of permanence. All that remained was being a mother.

She spent her latter years living alone and in terrible pain, stoically pretending that this was all part of her life’s plan instead of complaining. Mom always had a way of deflecting darkness, to a maddening degree. I don’t know if it was something she picked up from her parents during the Great Depression, or that she subsequently perfected as a result of burying them both on the same day. Whatever the reason, she never allowed herself to dwell on negatives, or to sometimes concede that things weren’t going well. I’d like to believe she always gave us plenty of space to feel down, and acknowledge we felt down, but at a certain level, how couldn’t we mimic her behavior to some degree? It’s all good.

The one time I recall Mom not being unquestioningly effusive in her support and encouragement, surprisingly so, was when I sent my parents a copy of the first article I ever published in a real newspaper—an op-ed trashing the glorification of Robert E. Lee in her hometown Dallas Morning News. The next time we talked, Dad issued a perfunctory compliment but Mom, a committed liberal, uttered something about my needing to be more respectful of other people’s heritage. She was raining on my parade—for the only time I could ever recall.

Years later I learned that my parents had just had their decisive break when I called to receive my pat on the back for my publishing debut. Mom’s grumbling over about Lee, and not the elephant in their room she was willing to shield me from, was her way of keeping a stiff upper lip. And so for years we played this awkward game in which she would have to half-heartedly defend Robert E. Lee, lest she confess that she’d been cornered into the position in a moment of despair. God forbid she acknowledge despair.

* * *

The day Mom died I got the call from the retirement home as I was picking up some things at the grocery store to bring to her in a few hours. Every time I pick up bananas now I remember that moment and how I abandoned my cart to run out of the store, grocery mission aborted.

The police officer sat me down in the lobby to inform me that Mom had passed peacefully in her sleep, seeming to belie the need to have a cop involved. What should be done with the body, he asked. I looked at him, befuddled, unprepared for the pace with which things were unfolding. The officer suggested that, for now, I go with a funeral home down the road and think things through overnight.

It wasn’t until about midnight that I remembered, with a jolt, what she wanted. Mom had been excited about donating her body to Georgetown’s medical school for research. She’d read a story about the program in The Washington Post three or four years earlier, and—it was all coming back—had signed up for it. Yes, there was paperwork about it somewhere. With mounting unease, I remembered something about how they were supposed to have been contacted immediately to retrieve the body. Yikes, was I blowing my mom’s death?

Early the next morning, I called Georgetown, and tracked down the right office only to be informed that they had no record of a Frances Jeanette Martinez in their registry. And it was too late to get her in at this point, but the clerk suggested I contact Howard and George Washington’s medical schools too, just in case they had a spot open. Apparently it is never too late to scramble to get into college; it can even be a posthumous source of stress.

It was so tempting to shrug off Mom’s desires and check off the cremation box at the funeral home, but I persevered. It felt important to do so, as anguishing as the additional uncertainty was. The Howard folks gave me a hard time on the phone for not setting up the donation earlier, but in the end they budged, and once I filled out the voluminous, notarized paperwork and assured them there had been no embalmment yet, Mom was picked up from her transitory funeral home. She was shipped off to medical school, for the sake of science, and some earnest med students who I often envision wondering what this corpse’s life—an empty journal to their eye—must have been like.

And it felt so right getting her into that school. The last thing Mom would have wanted is for her death to be about her.

Send A Letter To the Editors