Minor White believed that photography has the potential to spiritually transform the viewer as well as the practitioner. I can attest to that because it happened to me a long, long time ago.

I’m fortunate to have survived my 20s. Extremely fortunate. I now somewhat facetiously refer to that period as my “walking nervous breakdown.” But it was no laughing matter then. By all outward appearances I was just another tragic romantic suffering from the requisite melancholia, trying to find his way in a world that had little use for a former English major with a “thing” for Shakespeare and Milton. Inwardly, however, I was an angst-ridden mess fighting to stay alive.

Leading up to this crisis, I had suffered the end of a mad love affair, crashed two cars in two years (managed to walk away unscathed but totaled both vehicles, one in a rollover on Pearblossom Highway; neither really my fault, I swear), and dropped out of graduate school after having completed enough units for two master’s degrees.

Then things got rough. Fear crept in; well, actually, leapt in would be more accurate. It wasn’t until two years after sudden onset that I learned the word “agoraphobia” and that what I was experiencing were called “panic attacks.” We hear about the disorder all the time now, but it was news to me then. During those two years, I just thought I was going crazy and desperately sought a mostly DIY cure for that.

It never occurred to me to turn to Western organized religion for help. Eastern philosophy, however, was all the rage within the counterculture—the Beatles had pointed the way—so I read all the standard texts in currency at the time. The sixth-century B.C. Tao Te Ching, by Lao-tzu, was my favorite, the one that made the most sense and had a calming effect on me. I also sailed through Zen in the Art of Archery (seminal text), Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (one of many hippie Bibles), The Tao of Physics (too sciencey), The Tao of Pooh (the Bear; more helpful than you might imagine), The Crack in the Cosmic Egg, Exploring the Crack in the Cosmic Egg, the Earthsea trilogy (Taoism-influenced fantasy), some of Krishnamurti’s books, everything that Alan Watts wrote, and others too numerous to mention.

From all this material, I was rebuilding a man. But many of these texts contained rhetoric that I considered mumbo jumbo. What the hell was “suchness” anyway? And where was this Zen “still point”? Little did I know that I was about to find out.

While all this hyperfrentic reading was going on, I renewed interest in an old flame—photography. I’d taken it in high school and became the teacher’s lab assistant the following semester. I spent a lot of time in the dark, up to my elbows in chemicals. You—yeah you, with the 573 photos on your iPhone—you can’t imagine what a thrill it was to capture an image and watch it slowly materialize in the developer.

But photography was then a too-expensive endeavor for a student about to go off to college. The costs of a 35 mm camera, lenses, film, processing, and printing were prohibitive. So I stopped taking photographs seriously until my late 20s. One advantage of the blue-collar job I had at the time was that I could finally afford to purchase some decent used equipment. That’s when I decided that a creative life combining words and images would be ideal.

With borrowing privileges at half a dozen Southland libraries, I was able to check out and consume (for free!) books on all the great masters: Ansel Adams, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Walker Evans, André Kertész, Edward Steichen, Alfred Stieglitz, Josef Sudek, Edward Weston, and a host of others. Among these others, these lesser knowns (to me at least), was one Minor White. His name may sound small, but, as I was to discover, his spirit was large.

All I had to see was the cover image on the posthumous monograph Rites & Passages (1978) to realize that here was a kindred soul. White, too, had been steeped in Eastern philosophy. Without knowing it, I was inching closer to epiphany with every fevered page turn, and, suddenly, there it was: a manifestation of the Zen still point that I’d been reading about but failed to grasp until now: Windowsill Daydreaming, Rochester, New York (1958). Transformative? Most definitely. It spoke to me: Beauty and magic abound. Even in the seemingly simple things. Open your eyes. Slow down and LOOK, it said. Revel in the wonder of it all. From that moment on, I’ve been attentive to the minor miracles all around us.

Windowsill Daydreaming, Rochester, New York, 1958, Minor White. Gelatin silver print. The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2013.44.2. Purchased in part with funds provided by Daniel Greenberg, Susan Steinhauser, and the Greenberg Foundation. Reproduced with permission of the Minor White Archive, Princeton University Art Museum. © Trustees of Princeton University.

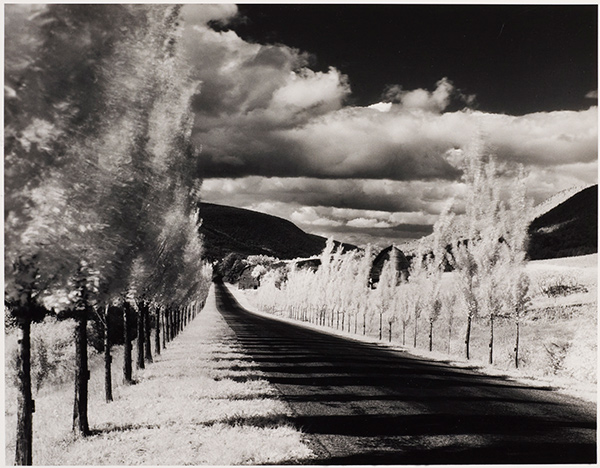

But there was more to learn from Minor White. Much more. The next image to captivate me from that same monograph was Road and Poplar Trees (1955). Why were the leaves white and so preternaturally luminous? I had no idea at first, but I did know that, more than anything, I wanted to journey down that road flanked by those brilliant trees.

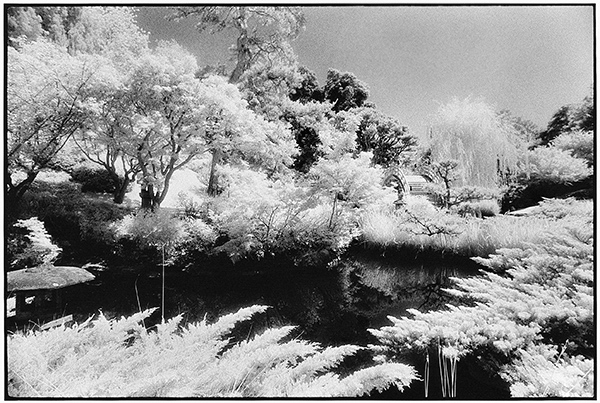

This photo and others sprinkled throughout the book, I discovered, were made from infrared film, which captures a wavelength of light humans can’t normally see. Extraordinary sights were hidden in this infrared range. All I had to do to experience it was load my camera with black-and-white infrared film, affix a red filter #25 to my lens, and step into another dimension of visual delight. What a feast! Seeing the world through rose-colored glasses is nothing compared to seeing it through a #25 red filter. Patterns emerged that I’d never seen before. Objects that heretofore seemed inanimate now possessed a life force. My planet, I realized, is dramatic, dynamic, exciting!

Lao-tzu’s Dream, n.d., Chris Keledjian. Gelatin silver print. Image courtesy of and © Chris Keledjian.

There is no doubt in my mind that photography, particularly two of Minor White’s images, helped me to survive, broadened my perspective, and enriched my life.

Send A Letter To the Editors