The Orange County Great Park in Irvine, California bills itself as “the first great metropolitan park of the 21st century,” but until recently it was the Marine Corps Air Station El Toro. The base was commissioned in 1943 and served as an airport for President Richard Nixon as he shuttled between the Western White House and Washington, D.C. After El Toro was decommissioned in 1999, the site was dormant for years. Then, after a long and contentious debate, voters approved a plan to create the Great Park. In 2011, I was invited to be one of the park’s first artists-in-residence.

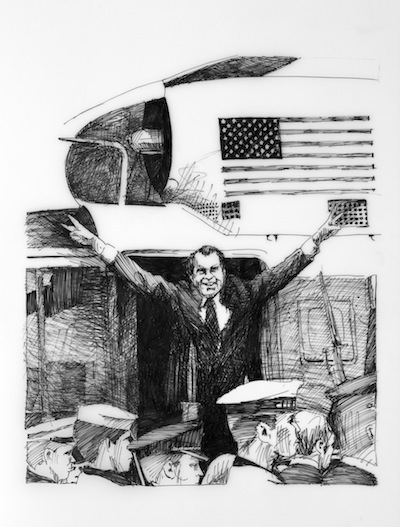

At the time, I was fascinated with what psychologists call “mental time travel”—the way old family photos or home movies can reanimate an emotion and cause you to re-experience physical sensations you felt at the time. It can also happen with historical events. Images of President Nixon’s resignation trigger a rush of feelings in me—even though I experienced the event as a 10-year-old watching it on television.

Orange County is a fertile site for Nixon time travel. The 37th president was born in Yorba Linda and lived in Whittier and San Clemente. I wondered if, when he visited El Toro, he ever stood on the site of my temporary art studio. When I looked out the window at the rows of newly planted date palms, I tried to picture jets on the runway, Marines in jeeps, and 5,000 supporters pressed against a chain-link fence waiting for the president to descend from the sky—to time travel to that unforgettable day in 1974 when Nixon landed here, a few hours after flashing his famous “V” sign and boarding his helicopter on the South Lawn of the White House for the last time.

I decided to see if I could trigger people’s “involuntary memories”—memories evoked by cues rather than conscious effort. I wanted to know if the former base was haunted for others, too. So every Sunday for seven months, I went to the park to hold “open studio” hours and asked people to tell me their memories of Richard Nixon. As people visited with me and told me stories, I worked on large pen and ink drawings based on well-known images from the Nixon presidency, and I made drawings to illustrate the personal stories I had collected from park visitors over the previous weekends.

The Vietnam War figured into many of those conversations. Every American man over the age of 60 told me his draft number and how he either served or avoided the war. People also told me about the antiwar protests at nearby UC Irvine, which surprised me. I taught in the university’s art department for five years and never heard anything about student protests.

In fact, I had an impression of Irvine as a placid postwar utopia. In conversations with park visitors, I heard about neighborhoods where you “felt like you were in the best place.” People told me about growing up in the newly built housing tracts of the planned community and described how the town smelled of the Eucalyptus trees planted as a windbreak between the orange groves and lima bean fields.

Irvine was a lima bean farm until 1960 when the University of California bought 1,000 acres from James Irvine for $1. At that time, California had a problem: The children of the postwar baby boom were reaching college age and would soon overwhelm the state’s educational institutions. UC Irvine was one of three new campuses to open between 1960 and 1965. President Lyndon B. Johnson presided at the UC Irvine dedication.

The layout of the UC Irvine campus and an adjacent community planned for 50,000 residents was designed by William Pereira, the architect who drafted the master plan for LAX. In photographs that ran in the September 6, 1963 issue of Time magazine, a dashing Pereira gestures to his blueprint of subdivisions and cul-de-sacs—“the perfect place to live, work, shop, play, and learn,” as described by Irvine Company literature.

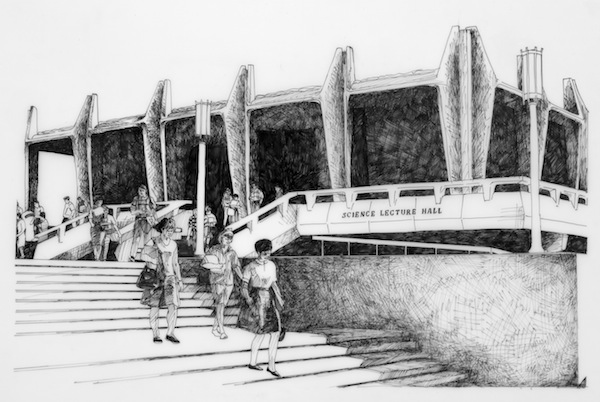

University of California, Irvine, First Increment (Irvine, Calif.), 1968, Julius Shulman. Getty Research Institute.

How did the Vietnam War transform this brand-new utopian campus? Inspired by my interviews at the park, I decided to investigate in the UC Irvine Archives and Special Collections at the Langston Library.

A sleeve of 35mm slides from October 4, 1965, opening day of the University of California, Irvine reveals many buildings still under construction, and bare ground dotted with fragile saplings staked to posts. Smiling girls with bouffant hairdos and boys with crew cuts carry armloads of books through William Pereira’s vision of the perfect future—all space age cement curves and expressionistic patterned facades.

Just a year and a half later, the students don’t look as happy. In a fat folder of slides from January 23, 1967, I find young people assembled with unmistakable seriousness on the steps of the Gateway Plaza to protest the firing of UC President Clark Kerr for his lenient treatment of Free Speech Movement activists (at the urging of recently elected Governor Ronald Reagan). The students are holding hand-lettered signs that say: “In Memoriam Clark Kerr” and “R-E-A-G-A-N Doesn’t Spell FREEDOM.”

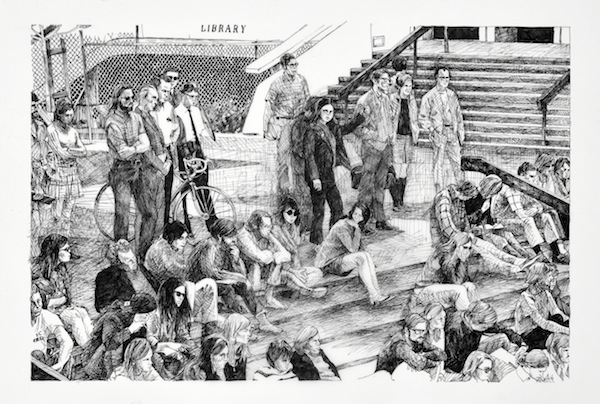

I see the students becoming more radicalized in dress and demeanor year by year. In bound volumes of The New University, the student paper, I read about how the campus participated in the nationwide Moratorium to End the War in Vietnam in October 1969. In faded slides, the clean-cut boys of 1965 are now shaggy-haired and shirtless. Girls have ditched their curlers for straight hair parted in the middle like Joan Baez, and they’re wearing jeans. They wear black armbands, and many students are barefoot. The crowd has swollen, completely filling the stairs, and legs are dangling from the library balcony.

Visitors to my Great Park studio had described their memories of April 30, 1970, when President Nixon appeared on television with a giant map of Southeast Asia to announce his expansion of the war into Cambodia. In response, students at over 400 colleges and universities went on strike. In a photo from May 4, 1970, the UCI plaza and library are occupied, and no one is smiling anymore. In one photo, a crowd holds signs that read: “Did Dick Ask Us?” and “Does your government represent YOU?”

I don’t think the protestors know it yet—the 24-hour news cycle hadn’t been invented— but National Guardsmen in Ohio opened fire on an unarmed crowd at Kent State University at 12:24 p.m. that same day, killing four students and injuring nine. Based on the angle of the sun and shadows on the plaza, the massacre in Ohio has already happened. It’s a weird feeling to know this has happened when the students in the photo do not yet know.

The speed of the transformation at Irvine is what affects me the most. In the five years since 1965, these brand-new buildings became symbols of an establishment the students felt had betrayed them. The students rejected the utopia that was created for them, not in a symbolic sense, but literally—this utopia was created for them.

The story of war protest at UCI may not be as historically significant or well-known as the protests at Berkeley, the University of Michigan, and Columbia University. But it is a microcosm of the rise and fall of the postwar American Dream.

I think about Pereira’s vision for a college campus as a tranquil utopia in an orderly, planned Southern California city, and try to reconcile that idea with images of Ohio guardsmen positioning their M-1 rifles in front of the pagoda on a picturesque campus 2,000 miles away. Tear gas blurs the silhouettes of students fleeing the Modernist cement buildings of Kent State, and in other pictures students crouch in a parking lot over the fallen bodies of their classmates. I guess it’s hard to “master plan” for some futures.

I put my folders back on the cart to be reshelved, wondering how long it will be until someone else asks to look at them. I emerge from the library into the late afternoon sun, blinking with the disorientation of a time traveler. I half expect to see picket signs and girls in ponchos. The Gateway Plaza is swarming with students, but they are of all different ethnicities, not the primarily Anglo students of the late 1960s. They are not shaggy but groomed and gelled. They’re texting on smartphones as they race purposefully to class. They have skateboards and backpacks, and it’s hard to imagine them protesting anything—not because they seem apathetic or indifferent, but because they’re so diverse it’s hard to imagine a single cause that could galvanize all of them.

The campus bears so little resemblance to the master plan that it’s hard to locate all eight original Pereira buildings amidst the expansion and constant construction. When I find them, the Brutalist buildings look dated and a little cartoony, dwarfed and crowded by giant glass and steel laboratories. The products of more recent architects—and their visions of an entirely different future—colonize every square foot of available space.

Send A Letter To the Editors