Amid Havana’s Daily Rations, Flashes of Serendipity

Photos by L.A.-Based Photographer David Stork Reveal the Rhythms of this Cuban Capital on the Eve of the 21st Century

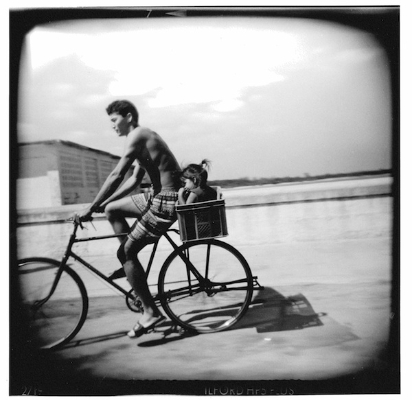

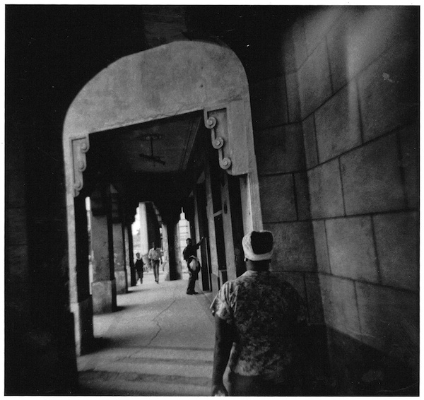

A kid jumps with both arms raised, while a group of boys look on to see if his basketball will make the hoop. A woman wearing a bandana walks under an archway. A shirtless man in flip-flops rides a bicycle with a crate holding a small girl.

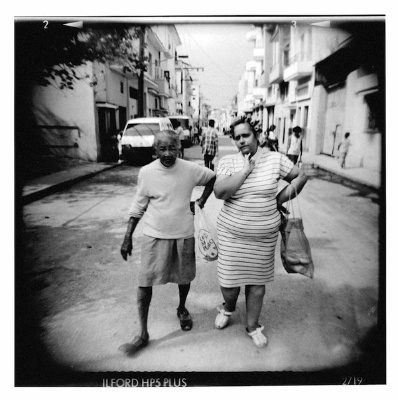

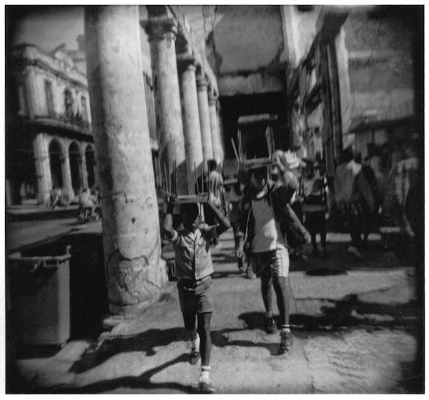

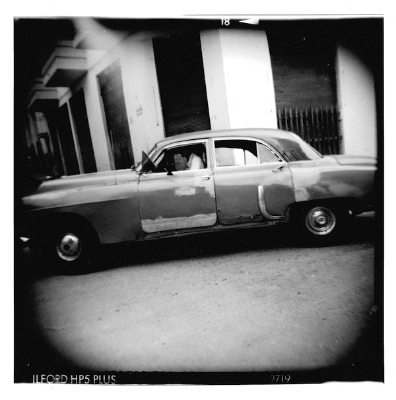

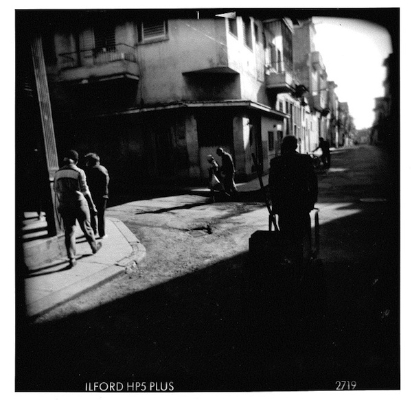

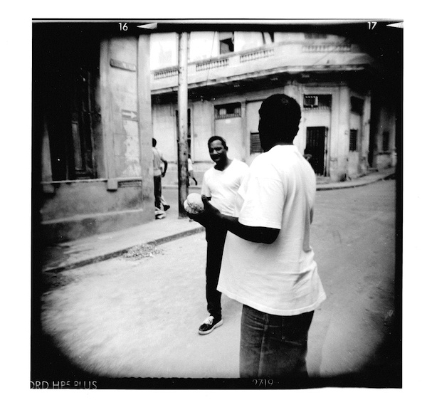

These are some of the moments captured in “Ten Blocks Square—Havana 1999,” an exhibition of David Stork’s photographs at the Couturier Gallery in Los Angeles. The black-and-white photos document daily life in Cuba at the eve of the 21st century—a time of food and fuel shortages brought on by the end of economic aid from the USSR.

Stork, an L.A.-based photographer, has a long relationship with Cuba, beginning in the 1980s when his father became the Dutch ambassador to the island, and Stork spent summers in Havana. At the time, Cuba was fully subsidized by the Soviet Union and a “lovely place,” said Stork. “There weren’t the issues that existed when everything slammed down on country in the ’90s,” he said.

When he returned in the 1999, he saw a very different country. He saw dilapidated buildings and tired, worn faces. He saw what he describes as a “rather desperate quality” in the people receiving their daily rations of bread.

Stork lived for two weeks in the center of Havana in the house where his wife, whom he met on a 1994 visit to Cuba, grew up, and his mother-in-law still lived. Determined to document life in the city, Stork set out every morning with his camera from the house to walk within a set area of five blocks in any direction.

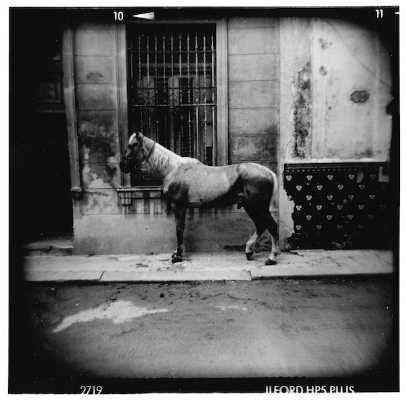

Instead of a high-end camera, he used a Holga, a cheap plastic camera made in Hong Kong. Because the film doesn’t lie flat and the lens is also plastic, there is a bent look around the edges of the frame and occasional distortion. The camera holds just 12 shots per roll, and Stork said changing the film in the daytime was perilous because the light could easily leak in and destroy the negatives.

“It was a pain, but I loved it,” he said, in part because of how the camera’s limited focal points and light settings impacted his photos. The pictures end up capturing what Stork feels was the way random, odd things often happened in Cuba—such as the moment he found a horse standing motionless and alone in the middle of Esperanza Street.

He shot about 45 rolls of film, developed them, then put the work away. This past fall—before Cuba made headlines with President Obama’s announcement that he was normalizing relations with the island—Stork pulled out the old photos. He was looking to put together an exhibition and realized that his work from 1999 showcased a moment in time in a country he loves in all its “intensity, sadness, and beauty.”

Stork may soon have another chance to discover how Cuba is changing. He and his wife are hoping to travel there for the first time in five years—though her entire family has already left. He’ll bring a camera, of course, and a pair of good walking shoes.

Send A Letter To the Editors