One hundred years ago, on November 25, 15 men climbed atop Stone Mountain, just outside Atlanta, touched a lit match to a kerosene-soaked cross, and resurrected a terror from America’s past.

One hundred years ago, on November 25, 15 men climbed atop Stone Mountain, just outside Atlanta, touched a lit match to a kerosene-soaked cross, and resurrected a terror from America’s past.

The Ku Klux Klan, dead for some 40 years, was back.

Their mission? To defend white, Protestant, native-born America from “illegal foreigners” and religious minorities. Faced with unprecedented ethnic and cultural change, at least 3 million Americans—South and North—responded by joining a violent, secretive movement, vowing to keep America from becoming “Catholicized, mongrelized, and circumcised.”

Today we misremember the Klan as faceless demons forever haunting American history. This lets us distance ourselves from the movement, but beneath those robes were ordinary Americans. And the Klan was not a constant presence: It was deliberately revived in 1915, when some in the white, Protestant majority became convinced that they were losing control of the nation to new immigrants and new values. The movement’s sudden resurgence offers a useful lesson today, warning about the dangers of backlash in the face of diversity.

Between 1915 and 1925, the “second Klan” conquered America in a way the post-Civil War organization, crushed by the government in the 1870s, never had. It won millions of members, 500,000 of them women. It took Texas by storm, and so dominated Georgia that the Klan held initiation ceremonies in the state capital building, but also metastasized across the north, from Asbury Park, New Jersey, to Portland, Oregon.

The citizens who flocked to the Klan were not wrong that America really was changing fast. By 1915, what was once an overwhelmingly Protestant nation had absorbed some 15 million Catholics and 3 million Jews. African-Americans, who had mostly been isolated in the South, were beginning to move north. Overall, America had a higher proportion of foreign-born residents than it does today.

The new culture of flappers and dancehalls seemed equally threatening. As young people enjoyed more sexual freedom, fundamentalists declared themselves “Puritan” defenders of old-fashioned morality “in this corrupt, jazz-mad age.”

This sense of alienation primed many to follow “Colonel” William J. Simmons, when he lit that cross on Stone Mountain. Simmons was a failed preacher—denied a pulpit for “moral impairment”—and actually never attained the rank of colonel in the military, but he was a brilliant organizer. In 1915, he took advantage of the immense popularity of the film The Birth of a Nation, which valorized Confederates and demonized freed slaves, re-launching the Klan as a blend of Old South nostalgia and Anglo-Saxon imagery. He added touches, like the Scottish burning cross (a symbol the 19th century Klan never used), creating an iconography so powerful it still generates goose-bumps today.

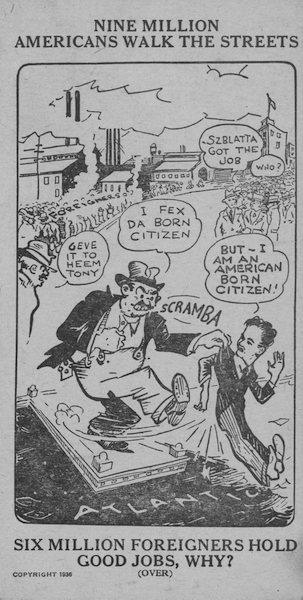

In the late 1910s and early ’20s, the KKK exploded in places like northern Indiana and California’s Central Valley, where diverse cities met the more homogenous countryside. Warning of an alien tide pushing in from the coasts, Klansman ranted about Catholic plots, Jewish conspiracies, or African Americans taking white men’s jobs. It particularly appealed to a slice of middle-class America that was equally hostile to urban professionals and working-class laborers. Klansmen argued that they were the forgotten real Americans, pressed from all sides by foreign forces.

The group was an odd hybrid—part terrorist organization, part social club. The Klan meted out horrific violence, flogging divorced couples in front of their children and castrating black men linked to white women, all the while insisting that their victims were being “punished in a spirit of kindness,” to protect them from sinful behavior.

But it also created a complex bureaucracy, complete with secret code-words and high-tech radio programs. New members even submitted their measurements to the headquarters in Atlanta to be fitted for tailored robes. Though the movement claimed to defend an older America, it was as modern as a Model T.

Pillars of American life backed the Klan. As one Oklahoma mayor put it, the KKK “made our best citizens their best friends.” Preachers gave approving sermons. Politicians endorsed the movement, turning the 1924 Democratic convention into a showdown between Klan supporters and northeastern liberals. Even policemen joined. When an Inglewood, California, cop shot several Klansmen during a fight, he found a constable and a deputy sheriff under the bloody robes.

When other Americans pushed back, like Kansas editor William Allen White, who called Klansmen “moral idiots” in white robes, the movement’s propagandists feigned victimhood, claiming that they were being persecuted by the media. Klan members were the true victims of “intolerance,” they declared. Anyone who said otherwise was “a malicious, slandering, lying fool.”

The Klan peaked in the mid-1920s, and crumbled after that. Even among bigots, the movement looked violent and corrupt. When the Louisiana Klan tortured two men to death for pulling off a Klansman’s hood, tying them down and running them over with a tractor, it made national news. The press kept up the pressure, reporting on the crimes committed by the “hooded hoodlums” who ran the movement. Membership began to collapse.

At the same time, America was incorporating recent immigrants. The KKK was always dwarfed by the tens of millions whose gradual acceptance helped make immigration to America among the most successful in world history. Public schools, popular entertainment, a booming business culture, and government programs helped fold outsiders into American life.

Today we can see, with a century’s perspective, the lesson of 1915. A prosperous, technologically advanced nation was not too modern to resurrect the worst elements of its past. A faction of the majority, feeling threatened by change, convinced itself it was an embattled minority, and embraced an apocalyptic fear that their stable civilization was far less adaptive than it proved to be.

As a curator, unlocking the metal cases that contain the Smithsonian’s collection of hundred-year-old Klan robes feels a little like a scientist handling those smallpox samples quarantined in isolated facilities. The off-white linen robes are at once an ominous reminder of something truly devastating in our past, and a pile of fabric, safely contained.

We can’t afford to forget those robes, snug in their storage units. In the 21st century, we tell ourselves that changing demographics will mean a steady acceptance of racial and cultural diversity, but the “second Klan” challenges this confidence. It’s hard to accept, but it was often easier to be a Jew in 19th-century America than in the early 20th century. African Americans enjoyed more rights in the years after the Civil War than after World War One. In the roaring twenties, and the pluralistic 2010s, progress is never guaranteed.

Still, what the Klan warned against has become America’s greatest strength: our ability to incorporate and synthesize. After all, the minorities the KKK ranted against joined mainstream American life whenever they could. Jewish, African-American, and Catholic boys, who were born as “Colonel” Simmons was lighting that cross, fought for their country in disproportionate numbers in World War II.

Ku Klux Klan propagandists fretted about the “mongrelizing of the citizenship of the United States,” but one hundred years later, it has only made us stronger.

Send A Letter To the Editors