Ansel Adams Captures the Struggle and Beauty of a Japanese-American Internment Camp

His Black-and-White Photographs of Everyday Life Showed These Families’ Strength and Resilience

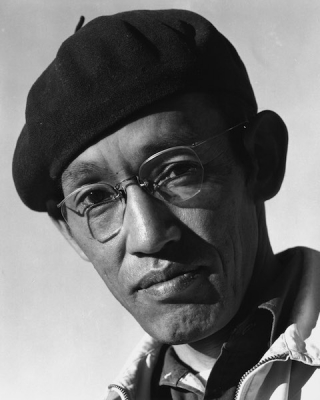

Any list of renowned 20th-century American photographers has to include Ansel Adams. His black-and-white landscapes of the American West are instantly recognizable, thanks in part to all those posters and calendars. What’s less well-known about Adams is that he tried his hand at documentary photography during World War II, when he focused his camera on scenes of life in the Japanese- American internment camp in Manzanar, California.

Any list of renowned 20th-century American photographers has to include Ansel Adams. His black-and-white landscapes of the American West are instantly recognizable, thanks in part to all those posters and calendars. What’s less well-known about Adams is that he tried his hand at documentary photography during World War II, when he focused his camera on scenes of life in the Japanese- American internment camp in Manzanar, California.

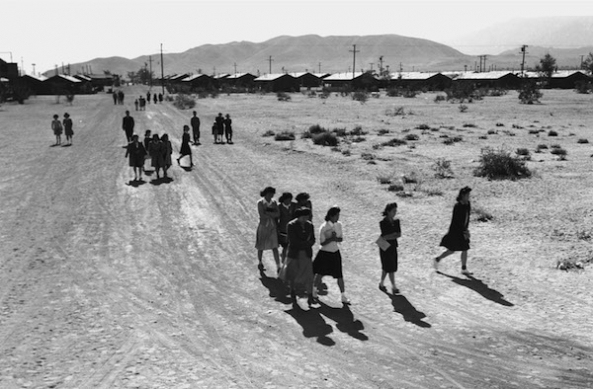

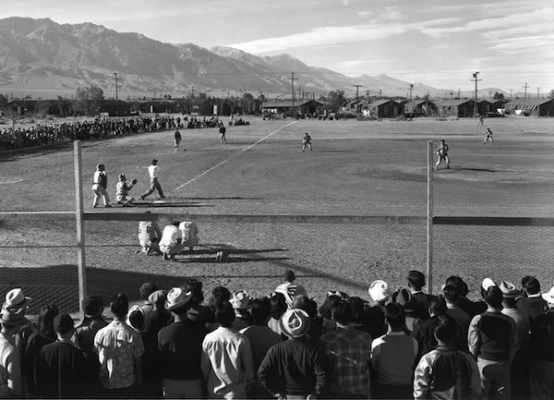

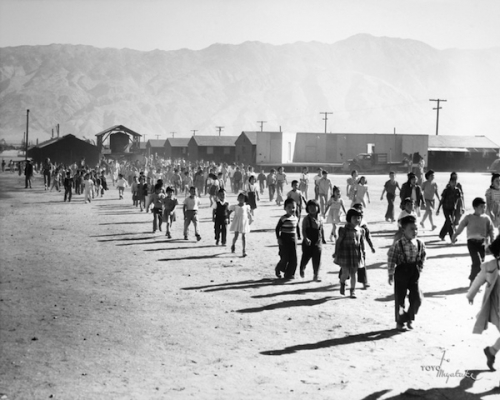

His black-and-white-photos include images of people going about their daily lives—schoolchildren during a fire drill, farmers at work in a potato field, a nurse in uniform. These are just a few of the 50 works included in “Manzanar: The Wartime Photographs of Ansel Adams” at the Skirball Cultural Center.

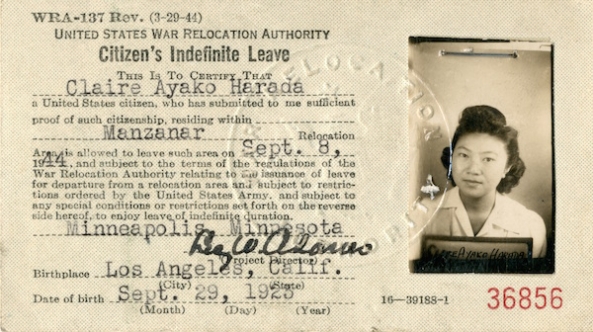

Adams went into Manzanar with a goal. “He wanted to show strength and resilience in contrast to the anti-Japanese imagery and racist sentiment that was out there,” said Linde Lehtinen, assistant curator at the Skirball Cultural Center. “He wanted to show these people as citizens—people who were making a community out of what was a terrible injustice.”

Presented along with the Japanese American National Museum, the exhibition features the work of several other photographers, including Dorothea Lange and Toyo Miyatake, as well as artifacts and other objects that document life at Manzanar—one of 10 “relocation centers” in the Western U.S. and Arkansas.

Adams’ Manzanar photos were published in a book, Born Free and Equal, in 1944. Reception to the book was mixed, to the say the least. There are accounts of so-called patriots burning the book and calling Adams “un-American” because he was sympathetic to Japanese-Americans, said Lehtinen.

But there were others—especially within the photography community—who charged that he did not show enough of the dark realities of internment. They wondered why people smiled and appeared so industrious under Adams’ gaze. After all, Manzanar was a prison camp.

Part of that had to do with timing, said Lehtinen. The camp had just been constructed when Lange visited in June 1942. She captured “stark, difficult moments of the forced evacuation” and a place that looked quite different from the one Adams first photographed in October 1943. By the time Adams arrived, people had tried to make improvements in the barracks where they lived. Instead of bare wooden floorboards, there was linoleum, for example. People also knew who Adams was and that he was coming to photograph them; they probably dressed in their finest clothes, noted Lehtinen.

Then there’s the matter of Adams’ photographic style, which was polished and pristine. Portraiture simply was not his forte—he was much more comfortable photographing the landscape.

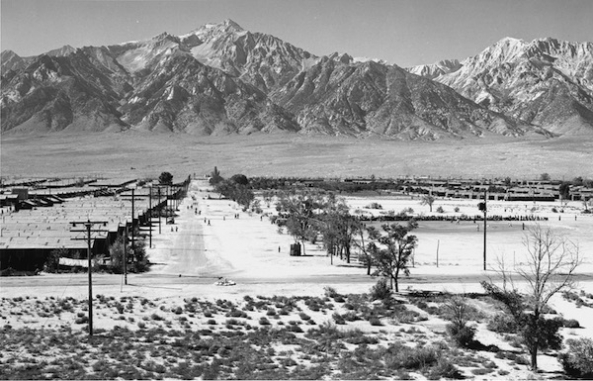

One photo in particular captures Adams’ deep attraction to nature and the goal of his project—to capture life at Manzanar. It’s a semi-aerial view of the camp through which clusters of people, mostly women, cross.

In this photo, “you’re able to see his interest in creating a panoramic view of this beautiful place—and I use that word because he saw it that way,” said Lehtinen. Residents of Manzanar lost their liberty and lived, worked, went to school, and even played baseball in the presence of gorgeous mountains. With his camera, Adams sought to document “how people lived in this place of terrible beauty.”

Send A Letter To the Editors