In 1846, shortly after his 24th birthday, Frederick Law Olmsted wrote to a friend, full of dismay about the prospect of finding a purpose in life. “I want to make myself useful to the world—to make happy—to help to advance the condition of Society and hasten the preparation for the Millennium—as well as other things too numerous to mention,” he fretted. “Now, how shall I prepare myself to exercise the greatest and best influence in the situation of life I am likely to be placed in?”

In 1846, shortly after his 24th birthday, Frederick Law Olmsted wrote to a friend, full of dismay about the prospect of finding a purpose in life. “I want to make myself useful to the world—to make happy—to help to advance the condition of Society and hasten the preparation for the Millennium—as well as other things too numerous to mention,” he fretted. “Now, how shall I prepare myself to exercise the greatest and best influence in the situation of life I am likely to be placed in?”

Little did he know he would end his life as one of the 19th century’s most influential Americans, a leading light in the emerging field of landscape architecture. He left his mark across the continent, helping to design more than a hundred open spaces from Central Park in New York City to the Stanford campus in California. Nobody of his generation did more to influence the way Americans think cities, suburbs, and wilderness retreats are supposed to look.

But while his name has justifiably become synonymous with the design of America’s great public spaces, thinking of Olmsted as just a skilled landscape architect is like remembering Martin Luther King, Jr., as just an eloquent speechwriter. Olmsted’s parks aren’t merely pretty places—they’re social arguments. They are some of the most important testing grounds for American democracy in action, places which express a confidence in our ability to recognize and promote the common good.

The dust-jacket pull quote on a new Library of America collection of Olmsted’s writings shows just how central social reform was to his work as a designer: “One great purpose” of park-making, in his view, was “to supply the hundreds of thousands of tired workers” with “a specimen of God’s handiwork.” In fact, it was this democratic spirit that animated Olmsted’s work from the beginning. One of his first insights into the progressive possibilities of landscape design came in 1850, during a visit to Birkenhead Park in England, where he enthused that “the poorest British peasant” could find the same enjoyment as the queen, since all the members of the community, rich and poor, shared “the pride of an Owner.” But it wasn’t until seven years later that a chance encounter in a café led him to a job as a construction supervisor with New York City’s nascent Central Park project and serendipitously set him on the career path that would make him famous.

By the late 1860s, after leaving Central Park to help found the Civil War predecessor to the Red Cross and then managing a mining estate in California, Olmsted finally committed himself to a permanent career as a landscape architect. Still, he kept up a dizzying roster of side projects, helping to edit the reform magazine The Nation and co-founding the American Social Science Association. His name even appeared (against his will) as a vice-presidential candidate in the 1872 election, nominated by a splinter group of Liberal Republicans.

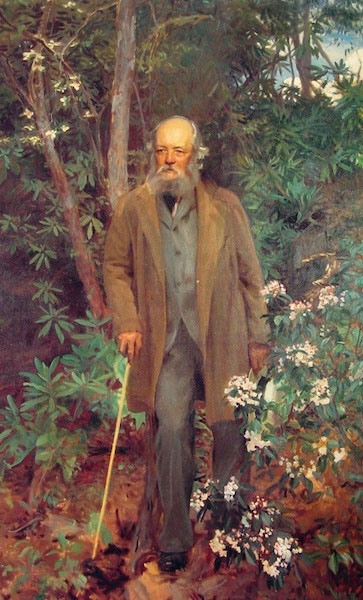

An 1895 portrait of Olmsted by John Singer Sargent.

During the course of Olmsted’s life, the patterns of the American landscape went through a dramatic upheaval. The fields and towns which had conditioned the values and interests of the early republic gave way to a new world of rail corridors and tenement districts, and the myth of a pastoral nation dominated by Anglo-Saxon property owners disappeared into the past. Americans of this era had to figure out how to live together in this radically different world. They faced the challenge of defining the stakes of community and shared responsibility in cities where people of many different classes, ethnicities, and occupations found themselves crowded together.

In an attempt to answer this challenge, Olmsted constructed the political justification for a new kind of public space. He believed that parks, financed and maintained by government agencies, were a common right of every citizen—a right which was particularly important for those who couldn’t afford good housing or a countryside retreat. And like many intellectuals of his generation, he held that experiencing “nature” was crucial to good moral and social development, and worried that the urban poor would be trapped in a cycle of inequality and social decay if they did not have access to the benefits of a healthy landscape. For instance, The Dairy in Central Park was originally intended to be just that: a social welfare agency that would dispense subsidized high-quality milk to Manhattan’s lower classes.

In an era of limited state power, such proposals were novel—and radical. Olmsted’s real skill, then, was his ability to lay out a case for the enlarged role and responsibility of public works. He wove together the principles of park-making with a broader commentary on the fate of American “civilization” in a way that conjoined politics, aesthetics, and philosophy. In this line of thinking, he tried to show that parks could hasten the emergence of a broad-minded public spirit that could transcend factional politics. In the place of “private and local and special interests” which were perpetually “antagonistic to each other,” Olmsted believed that the American landscape should be regulated “in the interest of all of whom the present public are the trustees.” He would return to this argument again and again throughout his life to fight back against those who saw parks as mere accessories to real estate speculation or mechanisms for pork-barrel spending.

As such, Olmsted deserves credit as one of the 19th century’s transitional figures: a thinker who was raised in an agrarian society, but strove to update the political rubric of American republicanism for a new age. His faith in the social possibilities of the public sphere became a keystone belief of the Progressive movement by the early 20th century, and it remains one of the fundamental principles of American liberalism.

In a report to San Francisco’s city government in 1868, Olmsted wrote how spending time in a public park infused citizens “with a common purpose, not at all intellectual, competitive with none, disposing to jealousy and spiritual or intellectual pride toward none, each individual adding by his mere presence to the pleasure of all others, all helping to the greater happiness of each.” To be sure, this optimistic faith in social consensus was naïve about class conflict, and Olmsted’s cultural template was sometimes snobbily patrician. But his belief that people could be made to care about each other through the careful arrangement of space arose from an insistence that hostile suspicion and self-interested competition were not an inevitable national destiny. As the new Library of America volume correctly observes, it was “communitiveness”—a term Olmsted coined to describe his faith in a social value that could supersede narrow individualism—which represents his “lasting contribution to American thought.”

Today, the American landscape is again in transition, placing incredible strain on the fabric of mutual purpose that holds us together. As the sociologist Saskia Sassen recently argued in The Guardian, cities are becoming the playthings of international finance, with the consequence that “what was small and/or public is becoming large and private.” At such a time, we ought to think about how to reinvoke the principles of an Olmstedian vision, in terms of neighborhoods, cities, and regions that reflect the collective enterprise of a complex society. As much as the Internet and other new technologies seem to have annihilated distance and turned us into generic threads in a worldwide network, we still long for good places to live: places of beauty, places of neighborliness, places of diversity and possibility. Olmsted’s parks are such places. They are a treasured and quintessential part of the American landscape: not merely for what they look like, but because of whom they belong to.

Send A Letter To the Editors