150 Years of Drawing ‘Wonderland’

From Woodcut Prints to Dalí Paintings, Lewis Carroll’s ‘Alice’ Has Inspired Artists and Made Books into Art

The Mock Turtle, the Cheshire Cat, Tweedledum, the White Queen: Few books have given us as many memorable characters as Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking Glass. Few books have seen their characters so often reimagined. That variety can be seen in a special exhibition assembled by Arizona State University to commemorate the book’s 150th anniversary.

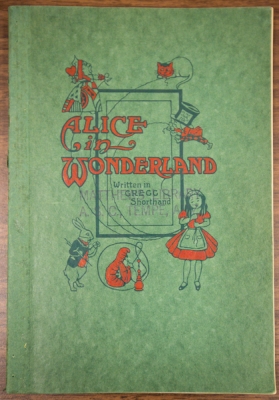

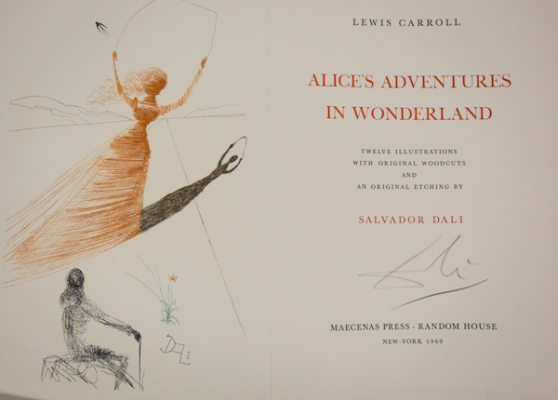

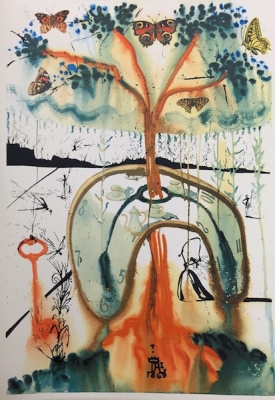

These include a Wonderland pop-up book by Nick Denchfield and Alex Vining from 2000, a version by Emma McKean from 1943 that features sliding panels with different illustrations, and an edition of Carroll’s text with woodcut illustrations by Barry Moser 1982. There’s a shorthand Alice. There’s a 3-by-4-inch Alice. Not to mention a set of Alice paintings by Salvador Dalí.

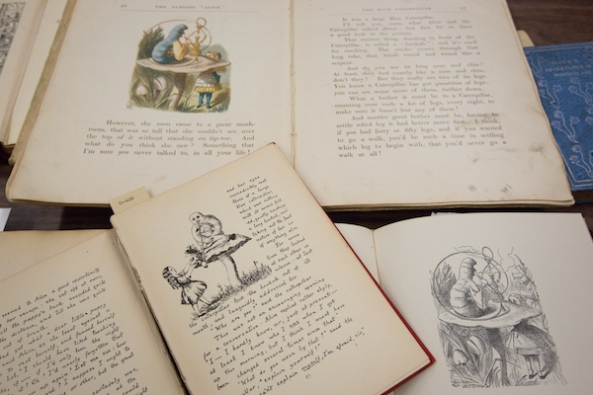

Illustrating Alice might seem like a foolhardy undertaking, given how memorable the original drawings by John Tenniel are. The ASU collections include several volumes that show his classic pictures, and subsequent versions can’t help but demonstrate Tenniel debts: The Mad Hatter in Robert Sabuda’s pop-up book, for example, is a familiar-looking tradesman. A political cartoonist for the magazine Punch, Tenniel worked closely with Charles Dodgson—the Oxford mathematician who took Lewis Carroll as his pseudonym—while planning and perfecting his Alice illustrations. Tenniel even suggested that one passage of the story be cut when he just couldn’t “see my way to a picture.” Carroll agreed. (The Annotated Alice, edited by Martin Gardner, includes those pages in an appendix.)

But even if Tenniel makes for a daunting predecessor, Alice’s Adventures and Through the Looking Glass remain tempting for artists. In these books, words and pictures are almost equals. They have been so from the beginning: Carroll’s original manuscript included his own illustrations, one of which can be seen at ASU. More than most, the stories depend on images. (At one point, Carroll instructs readers: “If you don’t know what a Gryphon is, look at the picture.”) It can even be tough to say where illustration ends and text begins, as in the famous case of the “mouse’s tale,” where Carroll intended his words to wind down the page in a diminishing tail. John Risseeuw, an emeritus arts scholar at ASU who taught printmaking and the history of the book, points out that Carroll’s whimsy gives book artists a lot of latitude.

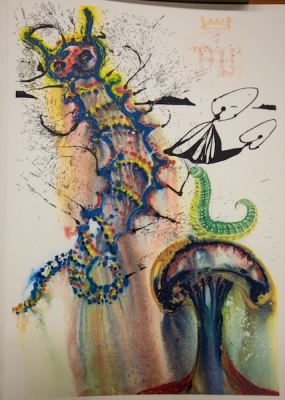

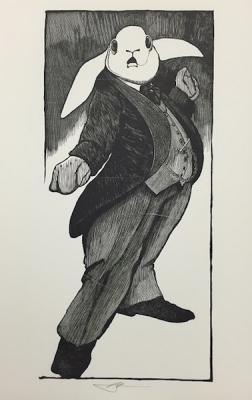

Even more important, perhaps, Alice and Through the Looking Glass abound in artistic inspiration. “The story is so fantastic and surreal that it provides a lot of opportunity for imagination,” said Risseeuw. The ASU collections offer proof—from Dalí’s colorful caterpillar, stretching across the page like a cross between Rorschach blot and rainbow, to Moser’s black-and-white rabbit, dressed in an imposingly proper three-piece suit. Risseeuw noted how Moser’s use of negative space differs from Tenniel’s. Moser’s prints are also deliberately imperfect, filled with tiny cracks that came from his using unseasoned wood. He invites readers to fill in the gaps with a pen—an unconventional but somehow Alice-like suggestion.

Different editions and illustrations show the importance of Alice—as well as the importance more broadly of books as material objects. The anniversary is “a reminder of how rich book culture is,” said Risseeuw, “and how much we get out of the physical object of the book, especially the illustrated book.”

Carroll would have agreed. “Did you ever see such a thing as a drawing of a muchness?” the Dormouse asks Alice during their Mad Tea Party. If she had, it might be her own story—in all of its versions.

Send A Letter To the Editors