As a teenager in South Los Angeles, I worked for Anti-Self Destruction, a government-funded neighborhood advocacy nonprofit. There I met Ollie, a handsome, slender supervisor who rocked lime green jumpsuits and sported a neat beard. One day I needed to talk to Ollie—he had been a Black Panther—about being more serious, more down for black folks, and being committed to the cause. He looked at me with perfect seriousness and said, “Just keep being your weird-ass self.”

I took his words to heart, and have never let them go.

I took his words to heart, and have never let them go.

I have never let South L.A. go either. I grew up in the middle of the Crenshaw-Baldwin Hills-Jefferson Park area, otherwise known as Black Los Angeles, a place that punched way above its weight as a center of black life in the United States at the time. Often when whites write (sometimes to great critical success) about Black L.A., they describe it as the sum total of its self-inflicted pathologies, rarely seeing the beauty of the particularity of life there or the complex intersection of class and intraracial conflict.

Sure, I got my ass kicked, and occasionally guns we’re pointed in my direction, but that could happen anywhere in the city of angels. The Black L.A. I grew up in is a moveable feast of memory.

My memories of growing up in Black L.A. are trips to Playa Del Rey beach and Griffith Park. My dad worked nights at the post office, and so he would take me and the neighborhood boys and girls all about the city on a regular basis. It was a one-man Boys and Girls Club. I’ve written many stories about Googie and Onla and the other knuckleheads I hung out with. I still think about the polite criminality and comic mayhem before rock cocaine came to town like an ill wind that kind of ethnically cleansed black folks who fled to the high desert or back to Texas, Louisiana, or Mississippi.

I remember going shopping with my mom at the Boy’s Market on Crenshaw when Crenshaw was still Japanese. And I remember hanging out in the magazine and book section and being terrified by Alfred Hitchcock short stories. Later I discovered that Japanese magazines had naked women in them but no one seemed to notice my 10-year-old self panting with excitement.

The nearby Holiday Bowl bowling alley was probably the only place in the world where you could get sashimi, hot links, grits, and donburi under the same roof. I was lucky to live on the edge of everything—the shining affluence of Baldwin Hills and close enough to the heat of working class neighborhoods. In 1964 we moved to a neighborhood of New Orleans expatriates, and I attended Holy Name of Jesus Christ Catholic Church on Jefferson. I attended their elementary school for just one year because a nun there decided that I was mildly retarded. My mother threatened to rip the veil off of the nun and I was sent to a public school to study with the heathens.

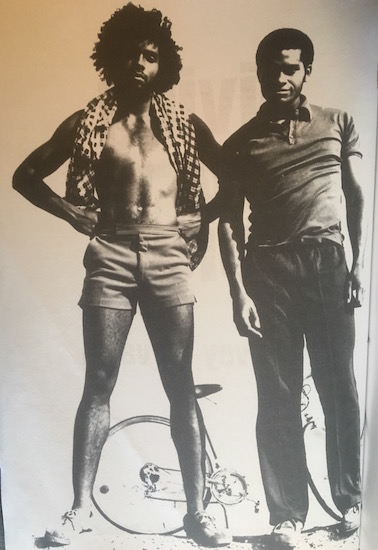

Jervey Tervalon, left, with a friend.

Long before Beyoncé, we were ensconced in celebrity culture in that South L.A. sightings of Muhammad Ali, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and Richard Pryor weren’t uncommon, and Jim Brown was known to crash a party. Who didn’t know someone who danced on Soul Train? Marvin Gaye was shot to death by his father on Fourth Avenue, walking distance from my house. And Jim Kelly, of Enter the Dragon fame, courted a lady on my block, though my friends and I would barely look in his direction because we thought he might round house kick our little pootbutts.

If you hung around long enough you’d end up in a movie, like my older brother who had a moment of fleeting fame in The Spook Who Sat by the Door. A casting director found him and his buddy in the unemployment line and needed some “high yellow niggers” for a few scenes for an important and complicated plot point involving passing as white and a bank robbery. My mom even sewed my brother’s dashiki for authenticity’s sake.

I had my distinctly out-to-lunch buddies; we carried staffs and wore flowers in our hair and, like Kwai Chang Caine meets afro hippies, we walked barefoot—and talked about science fiction and the horror fiction of H.P. Lovecraft incessantly. Perhaps not everyone is up on Afro-Futurism—that school of thought that values black speculative fiction as a necessary means to understand our current and past situations (though I think we thought of it as Afro-Presentism). Understanding white privilege in its myriad forms should be something you can get a Ph.D. in.

I had a great liberal arts education once I got to college, studying with the literary critic Marvin Mudrick—who understood that being raised in a real neighborhood meant you sometimes got beat up. My formal education meshed well with the idiosyncratic education I had before. Mudrick’s love of Chaucer became mine, and my love of Richard Pryor became his admiration. It’s the crazy complicated formula of one’s birth culture and its intersection with whiteness/European-ness and all the variations plus the breadth of one’s reading and interests. That’s how I thought of myself growing up weird ass Jervey, that dude who reads a lot and writes.

I also flew model rockets, studied martial arts, and loved science. I worshiped fan-boy culture: Dracula above all else, science fiction and Lord of the Rings, Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man and Ishmael Reed’s “I Am a Cowboy in the Boat of Ra,” Canterbury Tales, and millions of comics.

Later, when I did more traditional study of literature, my love for reading everything served me well. The canon couldn’t harm me or make me feel like an alien in my own skin—I took what was useful to me and ignored the rest.

I became a writer and teacher. Now, after teaching for over 30 years at almost every level of schooling, at some of the poorest and some of the most prestigious colleges and universities in Southern California, I’ve learned this: every teacher who ever meant something to me was passionate about his or her area of expertise, was generous of spirit, was honest, and made things.

It is hard to quantify these things, the metrics of creativity, but creativity and creative schooling can happen anywhere. Good, enthusiastic instruction. Decently paid, respected teachers. Students who feel respected and challenged. And a reasonable school environment. These are the essentials, but one can make do.

When I go back to South L.A., I teach junior high and high school students at USC’s Neighborhood Academic Initiative Saturday Academy. The academy is one of the enhancements NAI offers the kids in its seven-year program to prepare low-income students for college. (Those who meet USC’s admissions requirements get a full financial aid package). These are kids of color who can get into elite schools because NAI creates the kind of advantages an affluent kid has.

I’m glad for my uneven and even perilous inner city education—it made a reader and writer out of me. And so I do my best to entice NAI students to be passionate writers and readers. I flatter the ones who rise to the challenge and admonish the ones who don’t, even if they’re killing it in STEM courses. NAI and my organization, Literature For Life, give a $1,000 prize to the ninth grader who writes the best short story at a USC community school; we want to expand it to all public schools in L.A.

Too often these days we test kids like lab rats and torture teachers to achieve results that justify their jobs. I think of Melville’s “Bartleby, the Scrivener: A Story of Wall Street” and the power of saying “I would prefer not to.” I will not participate in a process that makes it impossible for a teacher to generate passion in students for reading, that values teaching to a test over the possibility of working to engage students in creative construction. STEM is necessary but so is reading widely and deeply. I want these kids to know the pleasure of reading Kafka and then being shocked that when they’re in biology, they remember The Metamorphosis and wonder about the nature of existence.

These Latino and African-American kids remind me of myself when I was in school, which happens to be the same school—Foshay—that I attended back when Foshay was a junior high and a tough place to be a student. Now Foshay is a K-12 school that produces students who get into USC, the UCs, Stanford, and Harvard. Many of them are the first generation in their families that will go on to college, and they look like me, and many of them are confident in their intelligence and wit.

They are their own weird-ass selves.

Send A Letter To the Editors