Is it “perilous fight” or “perilous night”?

We’re at a Dodger game and I’ve decided to just mumble that part of the national anthem. I see it as a victory that I don’t have to look at the Jumbotron for most of the lyrics, though my ignorance might shock or offend many Americans. How does an 18-year-old, born and raised right here in California, not know the entire “Star-Spangled Banner”?

That was two years ago. While I have since learned that it is perilous fight, I still don’t know the Pledge of Allegiance or the words to “God Bless America.” My knowledge of American history does not extend past the American Revolution.

But I’m not poorly educated. I go to an Ivy League school. And there are things I know that you do not. I can list all the regions of France (the past 22, not the newly condensed 13) and can sing countless German Christmas carols and nursery rhymes. I know all the words to “La Marseillaise,” the national anthem of France, as well as the significance of their national symbols, including La Marianne and the Gallic rooster. I can recite German folk tales, prayers, and poems. I also know the names of all of the French presidents and which Republic they were a part of (there were quite a few false starts), beginning with Louis-Napoleon, Napoleon’s nephew and an eventual emperor himself. I speak French and German fluently.

I’m not a French citizen (although I do know the process one must undergo to become one) and have no French heritage, and I was educated in Los Angeles. But in French. My elementary, middle, and high school, Lyceé International de Los Angeles (LILA), taught almost all of its classes in French. At the start of fifth grade, I distinctly remember counting how many hours of French I had a week: 12. That’s not including Art, P.E., or Math, which were also all taught in the language. By comparison, I only had six hours of English.

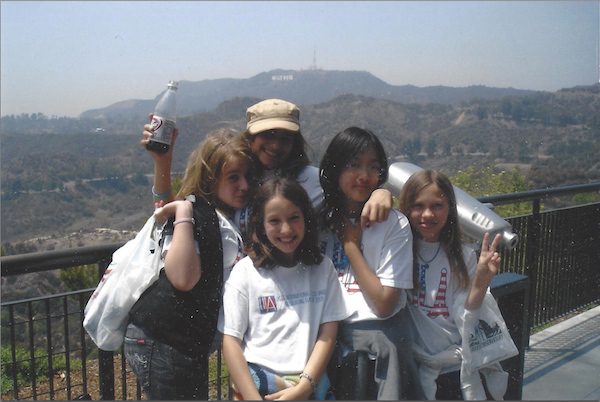

Jones (far right) on a school field trip with LILA to the Griffith Park Observatory.

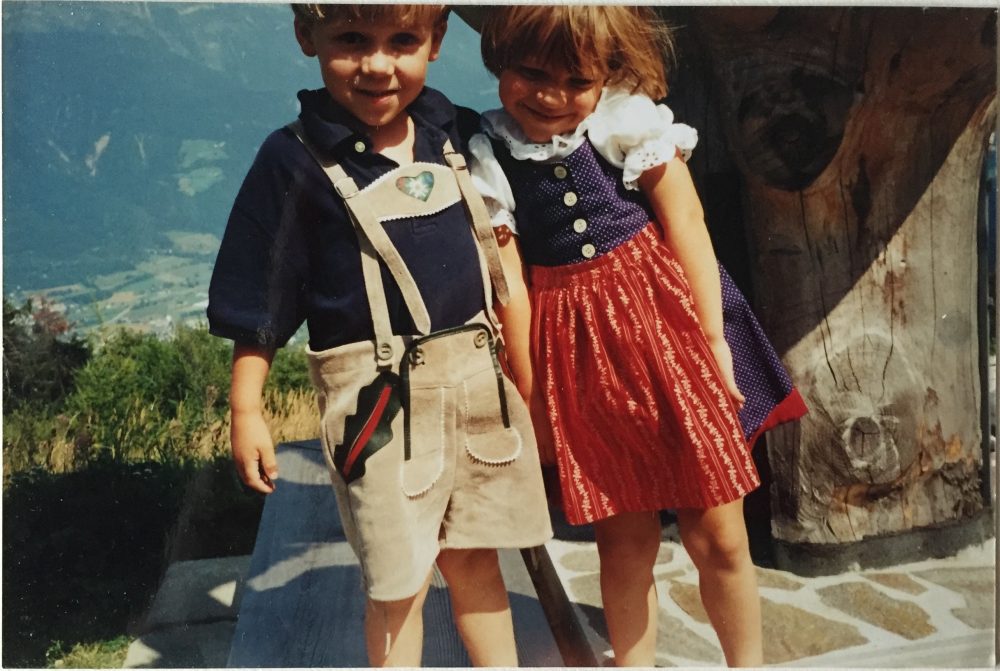

My relationship to German is the opposite. I’ve never taken a German class, but my mother and her relatives are German, and much of my large extended family still lives in Germany (our last family reunion took place in Kiel, on the shores of the Baltic Sea, and boasted 98 attendees). It is for this reason that German is my first language and I spoke it exclusively to my mother until I was 12. She refused to respond if I spoke to her in English, to ensure that I learned the language well and wouldn’t forget it when I grew up.

This determination is also why she sent me to French school. Not only did she believe that the French educational system was the best in the world, but also that an immersion school would guarantee I became fluent in yet another language.

It wasn’t until my brother and I were in the car with her, en route to our kindergarten interview, that my mother informed us that the school taught its classes in French. Despite not having any say in the matter, we were, apparently, unfazed. Another language, why not?

Indeed, I am grateful for my trilingual upbringing; it has enabled me to look at things from different angles and it has enriched my understanding of the world. But it also gave me a cultural affliction: I am an American whose entire perspective was shaped by a German heritage and a French education. Because of this layered detachment from the U.S., I’ve become a foreigner who is not remotely foreign.

I never joined the Girl Scouts or had a lemonade stand (although the latter may have more to do with my heavily trafficked Los Angeles street than my curious upbringing). I played soccer as a child, but I didn’t know the rules of American football until this year. The bedtime prayer I’d learned as a child was in German and told the story of 14 angels who protected me by standing at various places around my bed. I did listen to the Harry Potter books on tape in the car when I was little, and I did see one of the more recent Batman movies, but in both cases they were translated into German.

At my International Lycée (a term which refers to a secondary school that follows the French curriculum), where exotic nationalities were rampant, I was known as “the German kid. ” On one level that made sense—I speak German like a native and am well-versed in traditional songs and fairytales. But as a practical matter it was a stretch. I don’t know all that much about the German government or everyday life there, and—family reunions aside—my connections to the actual nation are minimal.

Jones (left) wearing a LILA t-shirt with a friend.

My knowledge of, and affection for, France, on the other hand, is borderline excessive. At the moment all I can think about is how this current U.S. election mirrors the French 2002 presidential election, and the ways in which Donald Trump resembles Jean Marie LePen. And when I recently read an article on “laïcité”, the oft-criticized French practice of imposed secularism, my thoughts immediately went to how endearing I find the policy. Rather than viewing it as an attack on religious freedom, I see it as a holdover from the French Revolution. In 1799 the French were doing everything in their power to separate themselves from the monarchy; they went so far as to invent their own calendar! Laïcité is their way of fighting against a tradition of religion used as force. It is the French trying to maintain equality, all these years later.

Sometimes I blurt out words like “flou” and “pechvogel”, which roughly translate to “imprecise and vague” and “someone who attracts bad luck”, respectively. I use them not because I’m trying to be pretentious, but because they express sentiments for which I have not found precise English translations.

This isn’t to say that I don’t love the English language; it’s actually my chosen college major. I also don’t dislike America, and I love California and Los Angeles. L.A. is a mixture of bewitching glamour and harsh reality, and I am lucky to have grown up here. But, on its own, it’s not home.

Truthfully, I’m a little lost. As I grew up my languages and my worlds became jumbled, and as a result I no longer fit into any of them. I’m not German enough to be German, I’m not French enough to be French, and I’m not American enough to be American. I have lived in the same L.A. home since I was two, but I didn’t speak English until I was at least three. My childhood was so filled with German that I dreamt in the language, but I know little about the realities of the nation. I have an American accent when I speak French, and of these three countries I have spent the least amount of time in France, but I know the most about its origins, politics and society.

Sometimes I wish I had a more clear-cut connection to a single place and culture. There is safety in having a true home. A place that, however boring or fast-paced, you know like the back of your hand, an expression, which, interestingly, has no direct translation into German or French. The closest you can get is “wie deine Westentasche,” or “comme le fond de ta poche,” which both roughly translate into knowing something like the inside of your pocket.

I’ve come to terms with the fact that I don’t have this exact relationship with a place, and that I may never. I need more than a place to feel whole. Los Angeles is only truly home when I’m with friends from my French school community laughing about Louis XV. When my mother makes bratkartoffeln and tells me about the German mystery that she’s reading. Or when I go to a small French restaurant in L.A. with my family on Bastille Day and we speak German the whole time. This I know, like the inside of my pocket.

Send A Letter To the Editors