Old homes on Adair Street, off Washington Boulevard near DTLA.

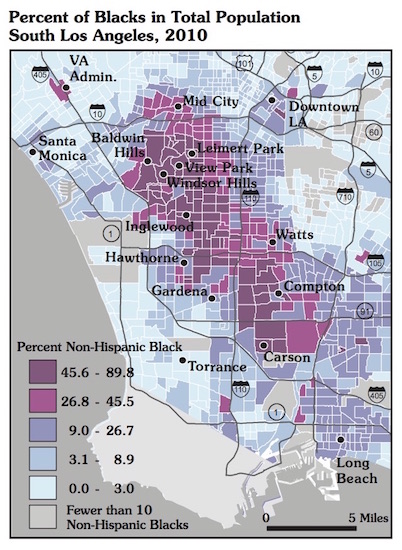

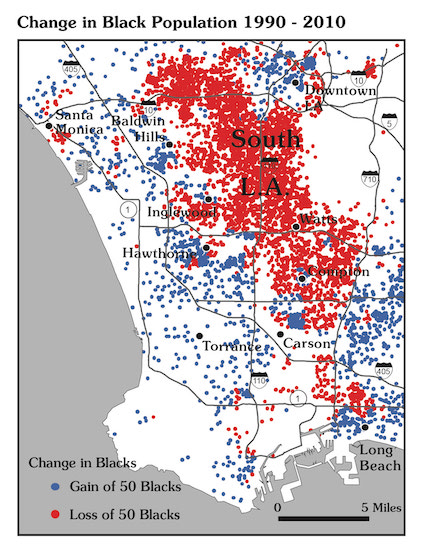

The first big change in South Los Angeles over the last half-century has been the shift of concentrated black communities westward into newer and better housing. The second big change is the replacement of those concentrated black communities, especially those near Central Avenue, by Mexicans, Mexican-Americans, and other Latinos.

The first big change in South Los Angeles over the last half-century has been the shift of concentrated black communities westward into newer and better housing. The second big change is the replacement of those concentrated black communities, especially those near Central Avenue, by Mexicans, Mexican-Americans, and other Latinos.

By 2010 this ethnic change in South L.A. had continued such that people of Mexican ethnicity outnumbered blacks everywhere east of Interstate 110, from Watts north to Interstate 10.

The two of us have long studied the ethnic quilt of Southern California, and recently updated our 1997 book on the subject. For us, the story of South L.A. is part of a larger, shifting story of segregation and desegregation. This second change—of blacks shifting and being replaced by Latinos— is not special to South L.A.; it has occurred in other once-segregated ghettos in Altadena-Pasadena, Monrovia, Pacoima, Long Beach, and San Bernardino.

Housing and home ownership are at the center of this story.

From roughly 1920 through the 1960s, white society generally did not permit blacks to own or rent housing outside certain areas. Restrictions on the future sale of a home to only whites were widely found on property deeds, and mortgage lenders usually restricted tightly the area within which they would provide a loan to a black family (a practice known as redlining).

Between discrimination in the job market and

low levels of educational attainment, even blacks who owned houses in these areas often did not have the money to maintain the housing very well. These difficulties in homeownership and maintenance resulted in increasingly poor and crowded housing in the ghettos. South Central (now South LA.), named because it focused along Central Avenue, was the largest such ghetto in the region.

When segregation began weakening during the 1960s, some middle-class blacks left behind the oldest and poorest housing east of I-110. They moved westward into other South L.A. neighborhoods or to Inglewood or southward into small cities like Compton, Gardena, and Carson.

While the public often associates the 1980s and 1990s in South L.A. with crime, the 1992 riots, and related challenges, there was another reality: housing prices were rising along with home ownership. In the 1990s, in fact, professor James Craine of Cal State Northridge has shown that housing prices in the South L.A. area increased faster than those in Los Angeles County as a whole. By the 2000 census, 40 percent of black households in South L.A. were owner-occupied, according to USC Professor Dowell Myers.

Behind those rapidly rising prices was strong demand on the part of Latinos, especially young Mexican and Mexican-American families. That demand, and the price trend, have mostly continued, with the exception of the Great Recession, which began in 2008.

One result: many black families in South L.A. have built substantial equity in their homes from earlier decades, giving them much more choice about where to live. And people have taken advantage of that choice, with former residents of South L.A. dispersing across other areas of Southern California.

Blacks in the San Fernando Valley, for example, have become widely distributed, though primarily in neighborhoods where housing costs are relatively low or average. In more distant places like Lancaster, Palmdale, Victorville, and Moreno Valley, some blacks were able to purchase inexpensive new homes, priced low because those locations meant long commutes to jobs.

Population numbers can disguise this dispersal. Between 1990 and 2010 the number of blacks in the five-county area increased by 1 percent. That small change hides the fact that blacks in Los Angeles County decreased by 6 percent during this period. But the number of blacks in Orange County grew by 43 percent during the same period, with even faster growth in other outlying counties.

Within the cities of L.A. County, a similar dispersal pattern emerges. Blacks now comprise just 9.6 percent of Los Angeles City’s population while blacks represent a quarter of the residents of Gardena and Carson. But the place with the highest percentage of blacks in the five counties of Southern California is a prosperous and unincorporated neighborhood bordering South L.A., View Park-Windsor Hills, where 85 percent of the population is black.

View Park is a reminder that the broader dispersal of blacks across the region is not the whole story. There is still a large area of South L.A. in which blacks comprise at least 45 percent of the total population. This includes View Park-Windsor Hills and the mostly middle-class black populations of Baldwin Hills and Inglewood.

Many blacks who could afford to move far from South L.A. prefer to stay more closely connected with community there, and some who have lived in neighborhoods with very few blacks have moved back to South L.A. for reasons of cultural comfort—to be closer to the institutions, services, and retailers that serve that large black population. Middle-class blacks have developed a strong social, cultural, and commercial focus in Leimert Park.

Despite the recent dispersal, Los Angeles remains quite segregated between blacks and whites. The level of residential segregation can be measured by what demographers call “the index of dissimilarity,” the most widely used statistic for this purpose. John Logan and colleagues at Brown University have calculated that L.A. is the 14th most highly segregated of the 50 U.S. metropolitan areas with the largest black populations.

But such a ranking represents an improvement. Our calculations for 1960 show Los Angeles as the second most segregated metropolitan area in the country; in that year, only Chicago was more segregated.

We have found the segregation that still lingers is no higher between whites and blacks than between whites and Mexicans, or Chinese, or Salvadorans, to name a few of the many new immigrant groups creating their own communities among friends and family who have also made the journey to Los Angeles County.

Those communities may too disperse in time. L.A.’s desegregation since 1960 was most directly the result of blacks moving slowly but steadily out of their segregated ghettos into what had been mostly white suburban neighborhoods. Our mapping shows that the major sources of the diminished numbers of blacks in L.A. County are still those leaving old black concentrations that had been built up in the days of segregated housing.

So South L.A., as now constituted, represents a legacy of both segregation and desegregation. Or to put it another way: South L.A. and its people, through their movement, have reshaped not only their region but also communities throughout Southern California.

Send A Letter To the Editors