The typical story of neighborhood change, often called ethnic succession, is one in which an incoming ethnic group “takes over” and wipes away the past. But that does not capture what’s happening in South Los Angeles.

The typical story of neighborhood change, often called ethnic succession, is one in which an incoming ethnic group “takes over” and wipes away the past. But that does not capture what’s happening in South Los Angeles.

South L.A. is both a remaining stronghold of African Americans in Los Angeles and a place where a new narrative of immigrant integration is unfolding. There, a process of building on the past—or ethnic sedimentation—has taken hold. As a result, South L.A. is now seeing the emergence of complex new identities rooted as much in a pride of place as they are in a sense of race. The area has become home to a new sort of Latino identity and a new sort of immigrant integration, both inflected by blackness.

Understanding these changes is important not just for South L.A. but for the country as a whole. Many other urban areas have been ravaged by unemployment, riven by immigration, and riddled by the rise of gangs and the hyper-criminalization of African Americans, especially, and Latinos. The kind of positive social innovation that’s happening in South L.A. as community organizations forge a Black-Latino unity could be instructive, with the lessons stretching beyond our majority-minority region and time, and touching on the future of the nation.

These conclusions come from research done by a team of colleagues and students at USC’s Center for the Study of Immigrant Integration in South L.A. over the past few years. We’ve observed public spaces, done detailed research in and on neighborhoods, and conducted interviews with 100 Latino residents and nearly 20 local civic leaders of all backgrounds. Our research team members are publishing the results in a new report, Roots|Raíces: Latino Engagement, Place Identities, and Shared Futures in South Los Angeles, combining our analysis with specific recommendations for South L.A.’s future.

Shifting Spaces: Demographic Change in South L.A.

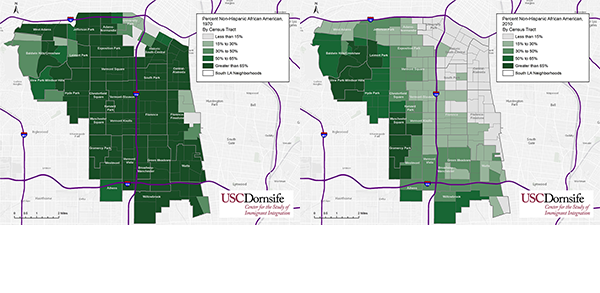

If there is a constant in South L.A., it is change. Once farmland, the area became the paradigm for white industrial suburbs in the 1920s through the post-war period. Black L.A., always a presence, grew dramatically in the war years, particularly along Central Avenue. After racially restrictive housing covenants fell, the black community moved south and west. By 1970, South L.A.—stretching from Interstate 10 to the north, the Alameda Corridor to the east, Imperial Highway to the south, and Baldwin Hills to the west—was 80 percent African American.

But time—and demographics—didn’t stand still. In the 1980s, job loss from deindustrialization and a toxic combination of high crime and excess policing forced many African Americans to reconsider their futures in the area. The 1992 civil unrest gave another push and as the exodus stepped up, Latinos moved into the neighborhood. Many were immigrants driven from Latin America by economic crises and civil wars, lured to the U.S. by changing labor demands, and unable to secure housing in densely packed traditional entry neighborhoods like Pico-Union. With the immigration flow also becoming more female and family-based, the search was on for affordable housing, and the single-family homes of South L.A. made for a good fit.

Non-Hispanic Black population in South L.A. in 1970 (left) and 2010 (right).

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Geolytics Inc.

Latino population in South L.A. in 1970 (left) and 2010 (right).

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Geolytics Inc.

The ethnic inflows and outflows were not balanced: More Latinos moved in than blacks moved out, and South L.A. became more crowded. Single-family homes frequently became multi-generational affairs, and Latino homeownership rates rose from 22 percent in 1980 to 33 percent in 2009-2013, nearly closing the gap with black homeownership. Now the area that has long been the beating heart of Black Los Angeles—South L.A.—is nearly two-thirds Latino.

The uptick in home ownership—as well as a steady increase in the share of South L.A. immigrants with more than 20 years in the country—signals the process of sinking roots. By contrast, other measures of “integration” or rootedness have remained low, including English-language acquisition and civic engagement. Here is evidence of a rooted but disconnected population: In 2013, while 47 percent of immigrants in Los Angeles County were naturalized citizens, just 26 percent of immigrants in South L.A. had that status.

Latinos in South L.A.: Generational Experiences

The first generation of immigrants in the neighborhood has complex attitudes towards their neighbors. In our interviews, older Latinos sometimes spoke of racial suspicion or, more commonly, simply noted relationships with African Americans that were polite but not close. But the very same individuals would later wax poetic about the African-American neighbor who guided them through the homeownership process, the black cop who set their errant hijo on the right course, and co-workers with whom they have shared struggles and triumphs.

What is clearer is that younger Latinos who grew up in South L.A.—the children of the elders—had very different experiences. The second generation has shared their lives with African-American neighbors—as classmates, teammates, and first loves. Said one Latino interviewee about interaction with African Americans, “You know, we grew up in each other’s homes, and we grew up together. So to us, it’s a similarity. They’re our people.” Another interviewee put it this way: “You are more in tune with the African-American community, you’re more mixed in.”

Strikingly, both generations are especially proud of being from South L.A.; they celebrate the neighborhood’s resilience in the face of challenges and injustice. Both older and younger Latino residents express a high degree of satisfaction with their community, seeing it as a place where they can realize their own version of the American Dream. Residents do not ignore the difficulties of life in South L.A., including household incomes for both blacks and Latinos that are far below the overall county average, but the struggle to overcome creates a tie that binds.

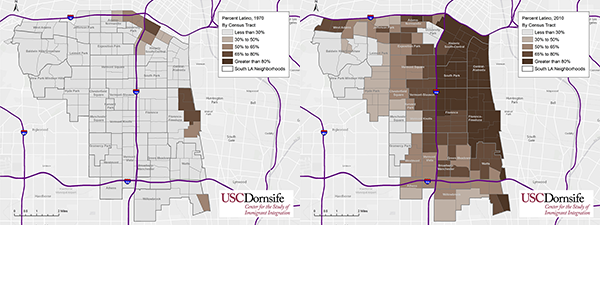

While the younger generation may indeed be “mixed in,” that has not necessarily translated to the public square. Latinos are dramatically underrepresented in political, non-profit, and other civic leadership roles. This is partly a consequence of the ways in which a more immigrant and younger population limits voting power; while South L.A. is nearly two-thirds Latino, Latinos comprised only 28 percent of the area’s voters in during the 2014 general election.

Bridging Race: Interdependence and Institutions

Moving forward, our analysis suggests that South L.A. needs strategies of both independence and interdependence. Independence includes leadership training for Latinos and the encouragement of naturalization and voter registration to coincide with the fight for the broader immigration reform.

Interdependence means avoiding “Latino triumphalism,” in which changing demographics yields a sort of “winner takes all, it’s our turn” kind of politics. While it may be easier for Latinos in communities where nearly everyone is Latino to pay less heed to coalition politics, such an approach is problematic in mixed South L.A., where effectively challenging racism (and, in particular, pervasive anti-blackness) and economic disparities requires the support of the whole neighborhood.

Bringing together groups while navigating differences is hard work, but some civic institutions in South L.A. are succeeding. One common thread among those doing black-brown unity work is a commitment to community organizing that is intentionally multi-racial in spirit and approach.

Organizers and civic leaders alike are especially sensitive to the palpable sense that Black Los Angeles is slipping away. To counter this, some organizations deliberately structure themselves so that blacks and Latinos have equal weight (even though the underlying populations may be more one group than another); for example, parent groups tend to be overwhelmingly Latino unless organizers make deliberate efforts to involve black parents.

Understanding personal histories, sharing stories of migration, and celebrating the struggle for civil rights in South L.A. can be key first steps. Organizers believe that such patient work pays off; for example, Strategic Concepts in Organizing and Policy Education (SCOPE) started a successful campaign for green jobs by first hosting a frank and far-reaching discussion on the evolution of black and brown communities in South L.A. Many organizations also find it critical to point explicitly to how pervasive racism is in our nation—how it is woven into the ways our institutions and policies are expressed in everyday life, and how this helps explain the exclusion of communities like South L.A.

Fortunately, there is much on which to build: organizations like Community Coalition (CoCo), CADRE, SCOPE, Community Development Technologies (CD Tech), and other multi-racial organizing institutions are turning out leaders who are imbued in this type of transformational civic leadership. CoCo is a particularly interesting example of leadership development and promotion: It was founded by Karen Bass and Sylvia Castillo—black-brown from the start—and recently President and CEO Marqueece Harris-Dawson, an African American who is now councilmember for District 8, has been succeeded by longtime organizer, Alberto Retana.

Facing Forward: Toward a Shared Future

There is more to do. South L.A. needs to step up civic engagement in general and Latino civic engagement in particular. This will require creating on-ramps to civic life for people with little history of participation, through activities like beautifying parks and staging community concerts. It also will require an emphasis on leadership: deepening Latino leadership for multi-racial coalitions, while strengthening black-Latino alliances, and enhancing capacity for existing black-led and other South L.A. organizations.

The public narrative also needs to change. South L.A. may be an area with many needs, but it is also a place with tremendous assets. New transit lines are bringing both greater mobility and needed economic development. New organizations are building ties between communities and ethnic groups long portrayed as at odds. New and creative strategies to realize the promise of South L.A. are emerging, with the most recent example being the successful multi-year, multi-sector, and multi-racial effort to secure the Promise Zone designation that will bring more federal resources to a large swath of South L.A.

Civic engagement of Latinos as a share of the total population in South L.A. and L.A. County. Source: U.S. Census Bureau, Geolytics Inc.

There are threats ahead. Nearly all the civic leaders we spoke with are worried about gentrification, particularly as downtown development spills south. Fears of displacement are not just economic; Blacks and Latinos alike worry that the community and neighborhoods they have fought so hard to build will be erased. Resisting—or, more accurately, taking advantage of rather than being taken advantage by new economic investments—will be an opportunity for new cross-community engagement.

In the last few years, knocking around the Twittersphere has been an inspiring hashtag, #WeAreSouthLA. It is meant to evoke a sense of pride in a place of struggle; it is frequently connected to people fighting for living wages and better schools, and against police abuse and racial discrimination. And if you peruse the tag, you will notice a myriad of faces, ethnicities, and genders all sharing joy about being from an area others have written off.

It is this more nuanced and dynamic picture of South L.A.’s past, present, and future that we have sought to capture—one in which organizing and civic engagement allow residents to achieve not only their of their own piece of the American Dream, but also their shared goal of economically vibrant, socially inclusive, and environmentally healthy communities.

Send A Letter To the Editors