Coyote as Clown, Cowboy, and Creator

Artist Harry Fonseca Transformed the Native American Folk Figure Into a Commentary on 20th Century Culture

In 2006, during the last few months of his life, the artist Harry Fonseca often spent Sundays in his Santa Fe studio with the curator Patsy Phillips. His ability to work curtailed by cancer, Fonseca liked to talk about making art, which he once called his “heartbeat,” and the ways in which it functioned as a conduit between his Native heritage and the world at large.

Fonseca was of Hawaiian, Portuguese, and California native Nisenan Maidu heritage. Thinking perhaps of some of the barriers he had struggled with during his own career, Fonseca told Phillips that Coyote—a figure who emerged in his early work and reappeared in many guises over four decades—was “often up against a brick wall as are so many Native peoples and artists … as soon as you’re born, you’re up against a wall. But it’s what you do when faced with obstacles that matter.”

Although Coyote could not heal Fonseca, who would die from an inoperable brain tumor in December 2006, he was a rehabilitative figure nonetheless. Tales of Coyote, the trickster and transformer, span many Native geographies and cultures, including those of the Plains, the Southwest, and the Pacific Northwest. A performer with the power to act upon the world, Coyote, in the assessment of scholar Jan Stryz, “violates not only social etiquette and mores, but physical limitations and definition. Is he man or animal? … Well, both, except when he has metamorphosed into a woman.” Coyote can be a clown and a creator; he deceives, but he also teaches and explains. One who simultaneously exists in the present and safeguards the past, Coyote has a lot to say about how life should—and should not—be lived.

Although Coyote could not heal Fonseca, who would die from an inoperable brain tumor in December 2006, he was a rehabilitative figure nonetheless. Tales of Coyote, the trickster and transformer, span many Native geographies and cultures, including those of the Plains, the Southwest, and the Pacific Northwest. A performer with the power to act upon the world, Coyote, in the assessment of scholar Jan Stryz, “violates not only social etiquette and mores, but physical limitations and definition. Is he man or animal? … Well, both, except when he has metamorphosed into a woman.” Coyote can be a clown and a creator; he deceives, but he also teaches and explains. One who simultaneously exists in the present and safeguards the past, Coyote has a lot to say about how life should—and should not—be lived.

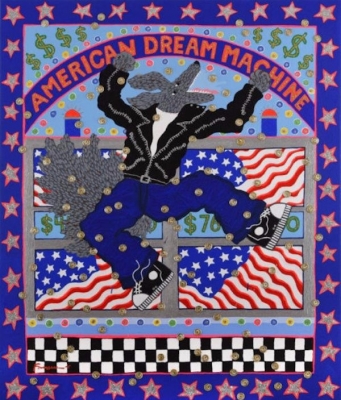

As a commentator on cultural values, Coyote is also a way for Native communities and Native artists to talk to and about the traditions they represent and the institutions that collect and display their work. With the recent acquisition of Harry Fonseca’s estate by the Autry Museum of the American West—including over a thousand works of art, sketchbooks, and archival documents—Coyote enters a space that is at once a cultural memory bank and a post-colonial institution, one that seeks to explore the legacies of expansion and conquest in 21st century terms. Two works, including American Dream Machine, in which Coyote is showered with gold coins, are on view now through June 2017 in the exhibition “New Acquisitions Featuring the Kaufman Collection.” A selection from the Discovery of Gold series will be featured in the California Continued galleries, opening this October. Plans for a future, more comprehensive exhibition and publication on Fonseca are also underway.

The Autry represents yet another space in which Coyote can play, enlighten, advocate, and critique, bringing with his endless transformations an aesthetic that celebrates the vitality of Native culture along with its capacity for metamorphosis and appropriation, without shedding its own significant, and often difficult, histories. Take Fonseca’s breakout works of 1971 and ‘72, in which Coyote “leaves the res” for San Francisco’s Mission District. Shown first on four legs, furry and snarling against a brick wall, Coyote quickly transforms: soon he is upright, in a black leather jacket with silver chains and platform boots. Although Coyote embraces Western culture broadly—reappearing as Prince Sigfried in Swan Lake, as Don Jóse in Carmen, dancing the tango, as Buffalo Bill, an Indian chief, a cowboy—there is something distinctly subversive about his ability to take on one icon, or one art form, after another. Coyote’s move from the “res” to the mission-turned-barrio-turned-counterculture destination is powerful in that it represents freedom, and his ability to act upon the shifting social, sexual, and urban geographies of 1970s America.

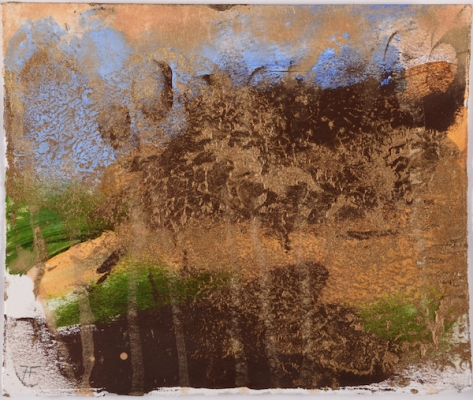

Within the context of the Autry, Coyote—and the Fonseca estate at large—further upends expectations by crossing lines between wide-ranging collections. Included in the estate are also series devoted to Fonseca’s unique take on Catholicism and the Mission System; the Gold Rush and genocide; and Ishi, the last of the Southwest’s Yaqui tribe. Like Coyote himself, these themes often function metaphorically, referencing historical trauma and the ongoing effects of what the artist once referred to as “the physical, emotional, and spiritual genocide of the native people of California.” And while he traversed historically difficult terrain, Fonseca also celebrated Native aesthetics on their own terms, in works that take joy in the abstract designs of regalia, the patterns of basketry and blankets, or the deliberately ambiguous imagery of petroglyphs. Nor did he confine himself to Native themes or aesthetics; the collection also features his forays into modernism and even pure abstraction, in works composed entirely of expressionistic drips or horizontal bands of color.

Whereas museums once represented “all that we have of the past,” changes in exhibition practice have given rise to an increased contextualization of cultural objects, and, increasingly, a seat at the table for those whose histories, traditions, and artwork is on display. No longer sealed off from cultural critique, the Autry, like all museums, can offer opportunities to interrogate the historical sources of its authority. Enter Fonseca and Coyote. Together they have the power to act upon the museum and the various narratives represented within it, both in terms of the objects on exhibit but also the viewpoints and biases embedded in exhibition practice. Exuberant and adaptable, yet never fully assimilated, the artist and his muse move from one setting to the next; they are both within and without the museum; they are everywhere and nowhere all at once.

Send A Letter To the Editors