Ed Ruscha’s Wild West

For 50 Years and Counting, the Artist Has Reinterpreted What the West Means to America

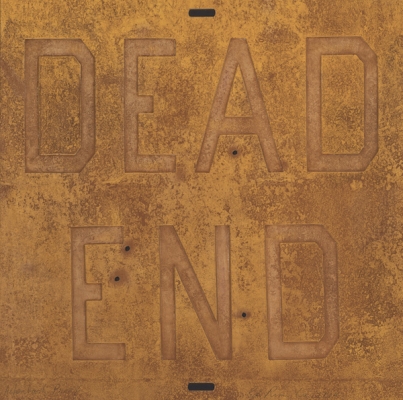

In 1956, at the age of 18, Edward Joseph Ruscha IV left his home in Oklahoma and drove a 1950 Ford sedan to Los Angeles, where he hoped to attend art school. His trip roughly followed the fabled Route 66 through the Southwest, and featured many of the sights—auto repair shops, billboards, and long stretches of roadway punctuated by oil derricks and telephone poles—that would provide him with artistic subjects for decades to come.

Ninety-nine of his works are now on view in Ed Ruscha and the Great American West at San Francisco’s de Young Museum. Visitors can take a visceral journey through the American West and the motifs that Ruscha found most fascinating and worthy of re-interpreting during 50 years of living and working in California.

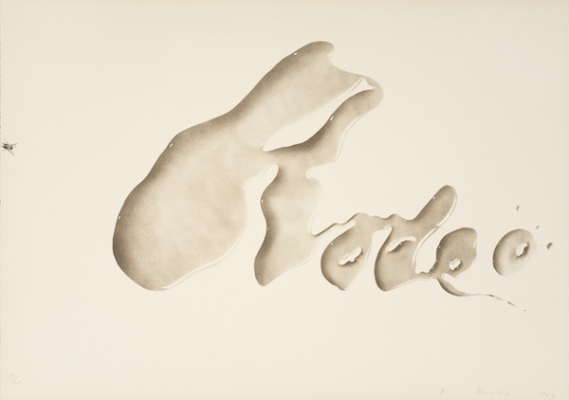

His notable captivation with landscapes is embodied in his depictions of sunsets with brilliant gradations of red, orange, and yellow. These often serve as backdrops for words or images that suggest the vastness of the western landscape and the enormousness of the sky.

Ruscha has spoken of this connection between the sky and the character of the region, saying, “The East I associate with steel and industrialism; the West with space and sunrises and sunsets.” The gas station has also been an important element of Ruscha’s work, and a photograph taken in 1962, Standard Station, Amarillo, Texas, became the basis for several of his best-known paintings and prints.

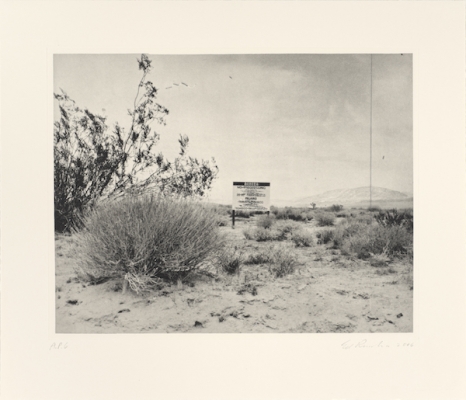

Ruscha also captured the changes in Los Angeles during the 1960s as it became a major urban center of the West Coast, while suburban sprawl and the construction of freeways contributed to its emerging car culture. He took hundreds of photographs from its roadways in a kind of documentary style—empty lots, apartment houses, and buildings along the Sunset Strip—and used them to create photographic books that were part artistic investigation, part visual travelogue of the eccentric and banal places in the city that had been built around and for the automobile.

Other works comment on the city and its cultural touchstones, including his famous “Technicolor” renditions of the Hollywood sign, and other subjects that symbolize the romantic aura and excesses of the film industry.

Today, Ruscha continues to work at the age of 78, maintains a studio in the California desert, and still makes regular road trips. Asked in 2011 about a road trip he would like to take in the future, Ruscha was optimistic: “It would need to be a dirt road somewhere here in the state of California in the desert, somewhere that lets me do some exploration on roads without any maps. There are still a few I’ve never tried, and I want to believe that wild spots still exist out there.”

Send A Letter To the Editors