The Swag—and Swagger—Behind American Presidential Campaigns

From a Coloring Book to a Painted Axe, Election Ephemera Remind Us of Hard-Fought Elections of Yore

America’s founding is rooted in the power of the people to select their own leader. Efforts to sway the vote—via gritty campaigns driven by emotion, piles of cash, and brutal, drag-out battles—are equally American.

Years, decades and even centuries later, the essence of these fights can often be glimpsed through their ephemera—the signs, slogans, and campaign buttons that both bolster true believers and aim to coax the reluctant into the fold. These objects can suggest campaign strategy as well as the temperament of the times. And they provide snapshots into that moment of possibility—physical artifacts with a potentially very short shelf life, infused as they are with the confidence of victory.

Nowhere are these stories better preserved than at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, where I work. The Museum’s political campaign collection is the largest holding of presidential campaign material in the United States and includes banners, signs, campaign ephemera, novelties, documents, photographs, voter registration material, ballots, and voting machines.

The museum’s collection includes artifacts that demonstrate an individual’s support for a specific politician, and reflect the pride with which many Americans have regarded their chosen presidential candidate:

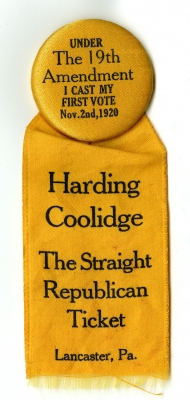

—A ribbon advertising the Harding-Wilson ticket of 1920 also celebrates the newly-passed 19th amendment, which gave women the constitutional right to vote.

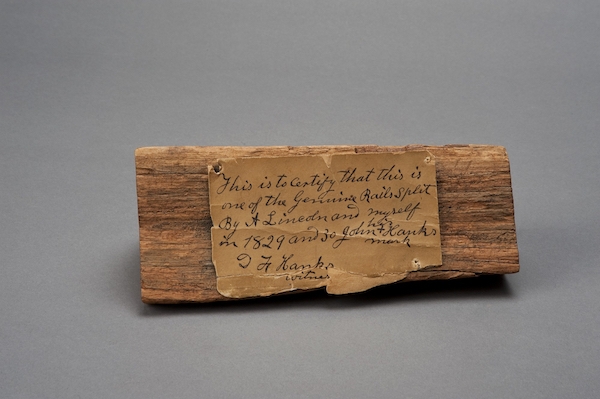

—A wooden axe carried in support of “railsplitter” Abraham Lincoln in an 1860 campaign parade assures the viewer that “Good time coming boys.”

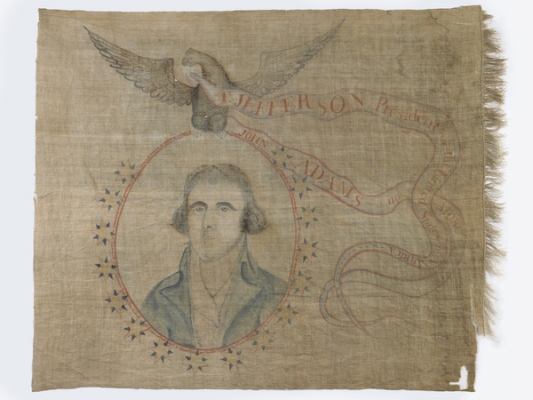

—A banner from the election of 1800, one of the oldest surviving textiles carrying partisan imagery, glorifies the victory of Thomas Jefferson while declaring—gloating— “John Adams is no more.”

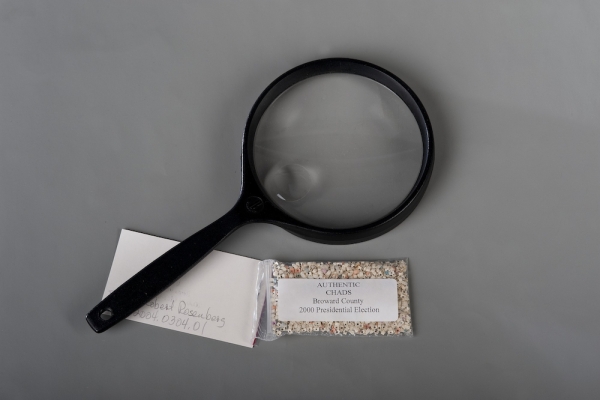

Other collections serve as physical record of major electoral events—the infamous “chads” from Broward County ballots were crucial to the outcome of the 2000 presidential election.

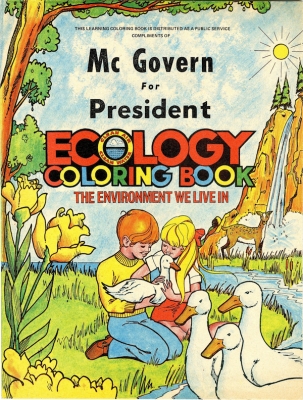

And some objects, like a coloring book about ecology produced by the 1972 McGovern campaign, demonstrate the different ways that political campaigns worked to connect with voters.

Send A Letter To the Editors