How the Skull Is an Ally in Art

When the Ultimate Symbol of Death Serves as Muse, It Can Force Us to Confront Our Own Mortality

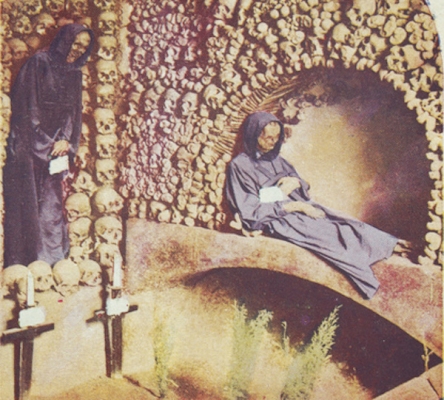

You walk through the darkness of the crypt, with choral music playing from hidden speakers. All around you, human bones are arranged in patterns, tiling the walls, divided by femurs, skulls, hip bones. Skeletal arms are crossed and nailed into the wall, making the symbol of the Franciscans, normally painted, out of the real thing. Even a child’s skeleton has been strapped to the ceiling, like a fleshless cherub, but decked out as the angel of death, scales in one claw-like hand, a scythe in the other.

You walk through the darkness of the crypt, with choral music playing from hidden speakers. All around you, human bones are arranged in patterns, tiling the walls, divided by femurs, skulls, hip bones. Skeletal arms are crossed and nailed into the wall, making the symbol of the Franciscans, normally painted, out of the real thing. Even a child’s skeleton has been strapped to the ceiling, like a fleshless cherub, but decked out as the angel of death, scales in one claw-like hand, a scythe in the other.

The scariest place I have ever been—that was not intended to be scary—is this crypt beside the church of Santa Maria della Concezione dei Cappuccini in Rome. At the foot of Via Veneto, the church contains a Caravaggio, but you could be forgiven for overlooking it, in favor of the adjacent vaults. For there lie the bones of some 3,700 former Capuchin and Franciscan monks, a haul that began with 300 cartloads of deceased brethren who accompanied the friars that founded this church in 1631 and added to it until 1870. What to do with this avalanche of human remains? The dead would be buried in the earthen floor for around 30 years, without a coffin, and then exhumed and transformed into decoration, to make room for the freshly deceased. Friar Michael of Bergamo led the initial arrangement of the crypts and their occupants, “burying” their brethren in a way that at once suited the available space—the walls, ceiling and floor of six vacant crypts alongside their church—venerated the remains, and created what many retrospectively label as one of the most beautiful, moving, and haunting art installations ever made.

If the message of this reburial-as-artwork was not clear, it is written into the floor of the final crypt, beneath the child’s skeleton: “What You Are, We Once Were, What We Are You Will Be.” Memento mori. Remembrance of death. Be a good Christian, before it’s too late.

As horror-filmic as the Capuchin ossuary chapels in Rome may sound, the creepiness of moving through them is cut by a cocktail of beauty (in the careful, aesthetic arrangement of this walk-through sculpture, for which bones happen to be the medium instead of wood or marble), tenderness (the hands of the friars who placed and fastened each component), and the sublime (the sweeping knowledge that death conquers all). For those who can’t walk these bone-covered crypts, memento mori can be appreciated on a much smaller scale—a single skull in some of the West’s greatest artworks.

Of course, the skull is a universal symbol. They are warnings of the possibility of death, flapping white on black on the Skull and Crossbones pirate flag, decorating the lapels of the SS, and on labels of poisonous materials. Prehistoric cultures displayed severed heads, and then the remaining skulls, of their vanquished opponents. Some Vikings made goblets out of the skulls of their defeated, which is perhaps the ultimate symbol of having conquered the body—not only did you kill and dismember it, but you repurposed the seat of the mind, the most human part of its corpus, and made it into something as mundane as a beverage holder. But these are displays of skulls as symbols, warnings—not artworks in the traditional sense.

Then there are vanitas paintings, still-lives that usually include a skull, among other inanimate objects that symbolize passing time—an hourglass, a burning candle, ripening then rotting fruit—as well as objects that are associated with vain youth, which will wrinkle, rot, and crumble in time—makeup, mirrors, dice. Philippe de Champaigne’s Vanitas (1671) is as good an example as any. From the artist’s perspective, these are exercise pieces, paintings of still-lives that allow you to show off your abilities at naturalistic reproduction, but to charge it with more meaning than a basket of fruit or vase of flowers alone might carry.

When the skull is taken out of a still-life and added to a religious work, it shifts from vanitas to memento mori. It’s hard to find a depiction of Saint Jerome without a skull. Jerome is usually shown naked in the desert, knelt before a cross and repeatedly whacking himself in the head with a rock, penitent and chastising his body in prayer. In these scenes, the skull serves as a reminder of a) Christ’s sacrifice, crucified at a place called Golgotha, which is Aramaic for “place of the skull” and which is supposed to have been the site where Adam’s skull lay, and b) the need for Jerome to hurry and engage fully in his prayers, before he becomes a skeleton, himself. The other version of Saint Jerome shows him as a scholar, in his study as he writes the Vulgate, his famous translation of the New Testament from Greek into Latin. In these images, as in Marinus van Reymerswaele’s Saint Jerome (1541), a skull gazes up from his desk, a ticking clock reminding Jerome and the viewer to be a good person (in pre-modern Europe that meant a good Christian) and to live life to the fullest.

A more complex version of the same Christian message may be found in Hans Holbein’s The Ambassadors (1533), famous for a mathematical/artistic trick, anamorphosis. This is a mathematical formula by which an image can be contorted or stretched in such a way that, when viewed normally from the front of a painting, it appears blurry or unintelligible, but when viewed from an acute angle or specific viewpoint, it optically “fixes” itself and we can see the image for what it really is. In The Ambassadors, what is ostensibly a double-portrait of two friends, the French secular and ecclesiastical ambassadors to the English court of Henry VIII, hides much more meaning. On the two-tiered table laid out between the two fully-painted figures are instruments to read the skies and constellations (telescope, astrolabe, celestial globe) and instruments of, or to measure, the earth (a ruler, books, a lute, a terrestrial globe).

But if we look closely enough, all is not well. On the celestial plane, the upper register of the table, it is as we would expect; but on the earthly level, the lower register, something is amiss, a-harmonic: a single string on the lute is broken, a reference to Henry VIII’s breaking with the Catholic Church and causing terrestrial disharmony. This message is further strengthened by the crucifix that peaks out from behind the green curtain at the back of the painting. This detail was only recently revealed after a restoration—it had been painted out at some earlier point, likely because it made too clear the underlying political message of this double portrait. But what people remember about the painting (my students, certainly) is the muddy shiver of white and black paint that appears to perhaps be a rug or tiles on the floor before the two-tiered table. It is only if you move to the far right-hand side of the painting (when facing it), and look at the painted floor from a tight angle, that the mess of white and black shifts into place before your eyes, and forms the shape of a giant skull.

Even in contemporary, secular art skulls remain (after all, we all have them), death remains, and all the symbolism that skulls carried in the past reverberates even today. Take the two most recent, famous skulls in art, two very different approaches: Gabriel Orozco’s Black Kites (1997) and Damien Hirst’s For the Love of God (2007).

One might assume that Orozco, who is Mexican, was referencing the Day of the Dead in this work—a real human skull which he spent months holding and drawing upon in pencil, in the shapes of squares, so the skull appears covered in a graphite and bone-white chess board (though the theoretically-even and consistent checkerboard pattern is contorted, as the squares bend around the contours of the skull). But Orozco disagrees, this is “an experiment with graphite on bone … The thing is a contradiction, really: a 2D grid superimposed on a 3D object. One element is precise and geometric, the other is uneven and organic. The two are not resolved.” It is certainly beautiful, and echoes the Capuchin ossuary chapels, in the communion of the artist, holding the skull of someone who once was, and drawing upon it—a thoroughly intimate act.

On the other hand, we have Damien Hirst mocking the commodification of art, by making what was the most expensive-to-produce artwork known (or so he liked to claim, though it’s a fair guess that works like the Colossus of Rhodes or the Athena Parthenos probably cost far more, in relative ancient world terms, than his 15 million GBP platinum skull encrusted with 8,601 diamonds). Hirst’s work is really the opposite of Orozco’s. Hirst’s skull is not real—it is a platinum sculpture onto which a ridiculous number of diamonds have been affixed. Hirst also did not make it himself, but commissioned a jeweler to do so. There is nothing actively human about For the Love of God, and perhaps that is part of Hirst’s point. In a 2008 interview about For the Love of God, Hirst said of death, “You don’t like it, so you disguise it or you decorate it to make it look like something bearable—to such an extent that it becomes something else.”

It is when the skull becomes not only something to fear, but also a friendly warning of life’s fleeting nature, that a universal symbol of death becomes a symbol of life. It is then that a skull is no longer just a lobe of bone, vacant sockets and remnant teeth, but a message loaded with additional, non-intrinsic meaning, then represented by human hand. Use the fear of death to inspire yourself to live life to the fullest. We have only so many grains of sand in our hourglass. In art, we can appropriate horror and make it our bone-winged ally, rallying us to seize the day.

Send A Letter To the Editors