The French have always loved Oscar Wilde, just as he always loved them. Long before Britain sent him to jail for enjoying sex with other males in 1895, he made Paris his spiritual home. He wrote the erotic tragedy Salomé (1892) in French, but the Examiner of Plays in London banned it after deeming it “half Biblical, half pornographic.” Much later, when he left prison in May 1897, he had to escape London, since his reputation there was ruined. So he crossed the Channel to Paris, where he resided, as “Mr. Sebastian Melmoth,” for much of the next three and a half years.

The French have always loved Oscar Wilde, just as he always loved them. Long before Britain sent him to jail for enjoying sex with other males in 1895, he made Paris his spiritual home. He wrote the erotic tragedy Salomé (1892) in French, but the Examiner of Plays in London banned it after deeming it “half Biblical, half pornographic.” Much later, when he left prison in May 1897, he had to escape London, since his reputation there was ruined. So he crossed the Channel to Paris, where he resided, as “Mr. Sebastian Melmoth,” for much of the next three and a half years.

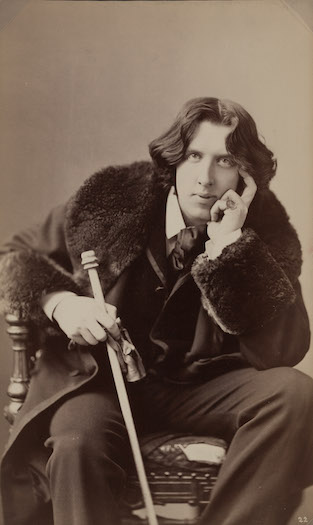

Napoleon Sarony, Portrait of Oscar Wilde, 1882.

When his health collapsed, he was laid up at the Hotel d’Alsace, in a seedier part of the Latin Quarter. He expired there—surrounded by hideous wallpaper—at age 46. A discreet burial took place at suburban Bagneux. At the time, it looked as if Wilde’s tarnished name would sink with him into the grave.

An exhibition now underway at the Petit Palais in the heart of Paris proves otherwise. Oscar Wilde: L’impertinent absolu offers as stunning array of artworks, manuscripts, and photographs that illuminate—as never before—Wilde’s legendary career.

This exhibition, on display until January 15, 2017, leads visitors through his phenomenal achievements, along with his difficult years of exile in Paris, and includes previously unseen materials from private collections.

The exhibition’s provocative title very loosely translates as “Insolence Incarnate” in recognition of the irreverent style that defines Wilde’s tremendous legacy. I recently spent several hours shuffling through with a busy crowd, all of us eagerly viewing the displays, arranged chronologically, beginning with letters from the time he excelled in Classics at Oxford and then moving to the paintings that he reviewed at the opening of the avant-garde Grosvenor Gallery in London.

Such works include G.F. Watts’s Love and Death. Wilde admired the strength with which “Love, a beautiful boy with lithe brown limbs and rainbow-coloured wings” tries to “bar the entrance” to the “giant form” of Death. Equally impressive among the artworks at the Grosvenor is Evelyn Pickering de Morgan’s Night and Sleep, featuring two entwined figures floating through the air, the one holding the cloak of darkness while the other scatters poppies on the earth below. Truly stupendous is James Whistler’s Nocturne in Black and Gold, The Falling Rocket, which caused outrage when John Ruskin alleged that the American artist had “thrown a poet of paint in the public’s face.” (A libel suit ensued.)

Napoleon Sarony, Portrait of Oscar Wilde, 1882.

As Wilde acknowledged, Whistler’s Nocturne—which brilliantly captures the fireworks at London’s Cremorne Gardens—counted among “the most abused” paintings at the London gallery. But he didn’t seem impressed. The painting, he observed, was “certainly worth looking at for about as long as one looks at a real rocket”—“for somewhat less than a quarter of a minute.” Together, these phenomenal paintings recreate the impact that the Grosvenor enjoyed in 1877.

Then, around a corner, there is the unforgettable image of Wilde as an aesthete embarking on a yearlong lecture tour of North America, where he spoke on “aesthetic” topics to bemused audiences. The famous theater entrepreneur Richard D’Oyly Carte recruited Wilde to deliver talks on the much-publicized English movement that championed art for art’s sake, seeking to bring beauty into everyday life. The tour supported Carte’s American production of Gilbert and Sullivan’s comic opera, Patience, which did much to promote the image of the modern art-loving man as an effete, sentimental, and somewhat vain fashionista. Wilde perfected this image. Especially striking at the Petit Palais is the complete set of photographs taken by renowned portraitist Napoleon Sarony in New York, just before Wilde launched his coast-to-coast adventures. He stands in a range of languid poses, sporting knee breeches, silken hose, and opera pumps, as well as a sumptuous beaver topcoat. Sold at every venue where he gave his talks, these images—over which Sarony controlled the copyright—ensured that Wilde became a celebrity icon. Americans were so taken with Wilde’s persona that caricatures appeared throughout the press. Meanwhile, advertisers adapted his “aesthetic” look for the sale of ordinary goods, including spools of cotton, carpets, and rugs.

Harper Pennington, Portrait of Oscar Wilde, 1884.

Once back in London, Wilde resumed lecturing. As he shared his “Personal Impressions of America” with British followers, he dispensed with his “aesthetic” garb and adopted more sober but fashionable attire. We can see his changing style in the full-length portrait that American painter Harper Pennington created for Wilde as a wedding gift. This imposing picture, in which the aesthete dons a fashionable frockcoat, has never before been exhibited abroad. It presents an attractive, poised 29-year-old man in the prime of life. His elegant walking cane planted firmly on the ground, Wilde returns our gaze with quiet reassurance. Initially, the painting hung in Wilde’s family home, where he moved with his wife Constance in early 1885. It was sold, however, along with his books and furnishings, during the court proceedings. Mercifully, two well-to-do friends—Ada and Ernest Leverson—rescued it, though in the wake of Wilde’s very public scandal Ernest eventually found it a source of embarrassment. Wilde ensured that it went to another friend. The public had no knowledge of the portrait until it was bequeathed to UCLA’s William Andrews Clark Memorial Library by Harrison Post, Clark’s romantic partner, more than 80 years ago. In May 2017, the artwork will be a centerpiece in Tate Britain’s “Queer Art in Britain, 1885-1967.”

Oscar Wilde: L’impertinent absolu traces his evolution into a major writer. This was the period when he enjoyed a blissful marriage, for a time. Particularly joyful is a photograph of Constance embracing their oldest boy, Cyril. The mid 1880s was also the period when Wilde made his mark with his classic collection of fairy tales, The Happy Prince (1888). A central part of the exhibition shows how successfully Wilde built his relations with French authors, including Stéphane Mallarmé. Other continental figures are equally well represented: Maurice Rollinat, Pierre Louÿs, and Henri de Régnier, as well as J.K. Huysmans, whose anti-realist novel, A rebours (1884), left a deep impression on Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890, revised 1891).

The Picture of Dorian Gray was a turning point. A small but vocal minority of critics denounced it for its homoerotic subtext, and so it gained Wilde notoriety. By 1892, his first comedy, Lady Windermere’s Fan, wowed the London stage with Wilde’s aphoristic wit. Three more triumphant plays followed. In the interim, he started focusing his personal life on other men. He became intimate with an Oxford undergraduate, Lord Alfred Douglas, and he slept with several younger males, some of whom traded in sex work and extortion.

The Cameron Studio, Portrait of Constance and Cyril Wilde, 1889.

Most intriguing to me was the exhibit showing a single opened-out leaf of a hefty document. This is the set of witness statements from Wilde’s libel suit against Douglas’ father, John Sholto Douglas, 9th Marquess of Queensberry. In early 1895, Queensberry—a hotheaded Scottish lord—penned an insulting visiting card (with an infamous misspelling) declaring that Wilde was “Posing as Somdomite.” Wilde sued for libel. Yet the witness statements show the extent of Wilde’s homosexual contacts. Once the libel suit collapsed, the authorities decided to prosecute Wilde, and the controversy that followed preoccupied the press for weeks before he was sentenced to two years in jail.

Wilde’s reputation began to revive not long after his demise. Richard Strauss’s Salome (1905), which features in L.A. Opera’s current season, helped turn the tide. And the publication of Wilde’s prison letter, De Profundis, did much to rehabilitate him in the same year. More than a century later, Oscar Wilde: L’impertinent absolu reveals how strongly Wilde speaks to us now. It also reveals—for all his lasting fame—that much remains to be learned about Oscar Wilde.

Send A Letter To the Editors