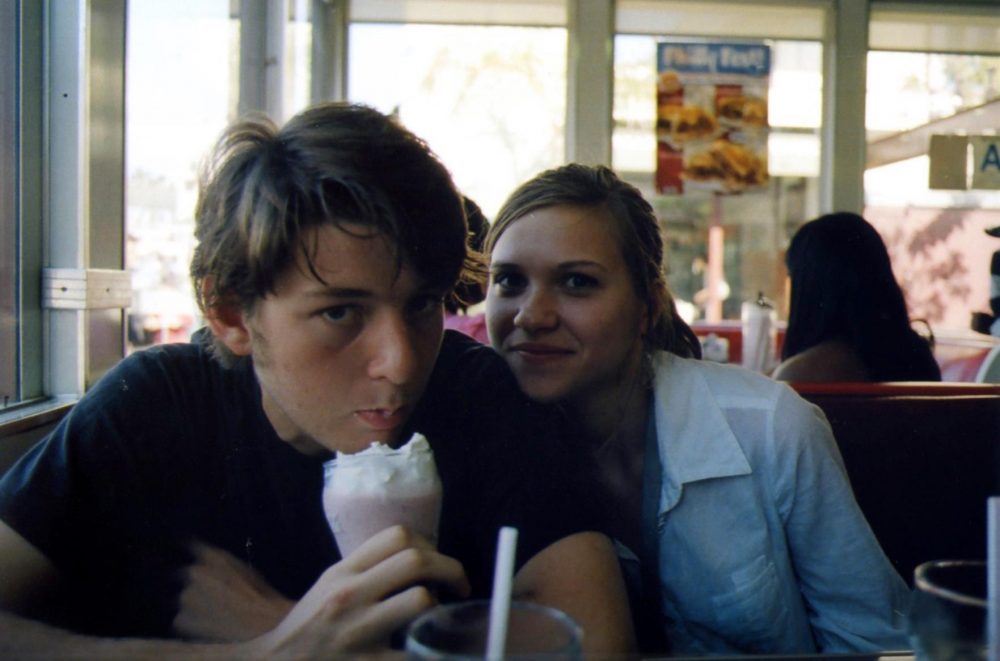

AJ (left) and the author. Photo courtesy of Emma Electra Jones.

I suspected that something was wrong on the Sunday morning when I saw the beginning of a Facebook post in my newsfeed sidebar that said, in French, “Our dear AJ has given up …” I was unable to read the rest because it was removed as I looked at it, but I was concerned that it might actually mean that AJ was hurt or in trouble.

It could have said something like, “AJ has given up his studies,” because the French wording is similar for all scenarios. That particular formulation is most often used in reference to death, true. But on this quiet Sunday morning, when I was about to go grocery shopping, I found the concept outrageous: AJ was simply too real to me to turn up dead online.

AJ loved the L.A. Zoo, Donald Duck orange juice, and cats. He often held his arms close to his chest, like a T-Rex. He was sarcastic. He could play the guitar, and would sometimes play mine, but he didn’t sing. He was very much alive in my mind.

I texted Fergus, a mutual friend from high school: “AJ is fine, right? He didn’t kill himself or anything.” Fergus texted back: “I don’t think he killed himself. Nico got a Snapchat from him the other day.” The text tone was mocking. I didn’t text AJ for this very reason; I was so sure that he was alive that I thought he, like Fergus, would make fun of me for being worried that he was dead.

So now all was presumably well. We had Facebook, we had Snapchat, we knew what was going on! I responded with “Ok yay, glad AJ is still alive!” and Fergus and I continued to debate whether pancakes or waffles were tastier. Something significant and heart-wrenching had happened, but it quickly disappeared, lost in the way social media collapses all distinction between the trivial and the profound.

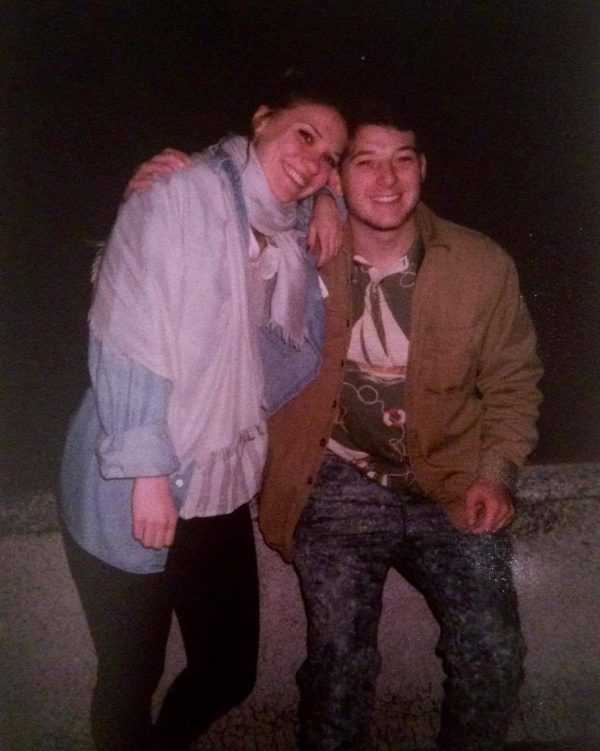

The author (left) and AJ. Photo courtesy of Emma Electra Jones.

I met AJ sometime in the fifth grade. At first we weren’t friends. In fact, I hated him for a good portion of the sixth and seventh grades in that irrational way that children sometimes hate one another. Eventually I no longer found him an awful person to be around, and we were good friends throughout high school. When we went off to college we carried on our friendship online—the way my friends and I do almost everything. But an unforeseen hazard of living life online is that it confers a kind of immortality that doesn’t square with real life—and certainly not real death.

Around 11 p.m. that same Sunday, I was cooking chicken-less chicken nuggets for a group of friends in my New York apartment when I went to my bedroom to grab my phone. There was a text: “Emma, AJ did kill himself. I’m sorry if you wake up to this.” Fergus had just gotten off the phone with AJ’s mother. Later, I would find out that he had died two days earlier after overdosing on heroin. I would learn that he was an addict and had overdosed once before. I would remember that he’d dabbled with drugs while we were in high school. But the moment that I read those words, the only thought that came to mind was being 16, out past curfew, parked somewhere in the Hollywood Hills, and as I collapsed in the hallway of my apartment, weeping, I kept repeating: “Oh my god, I kissed him in the back of a truck and now he’s dead.”

I had some previous experience with death: the passing of a great uncle. The sensations that I was having now, though, were new and horrible. This death made me frantic. Finding out that a close friend has died without any human contact, not even the sound of another person’s voice, is disorienting. For me there was no ritual to delineate when he had died and when he had lived—no sheet pulled over the face, no pennies on the eyelids, no pronouncement and silence.

That night everyone who knew him was bewildered. We exchanged shocked online messages. Was this real? Could these texts be trusted? Because that’s all anyone was getting: texts. The mother of a friend of mine was waiting to tell her children until she had “more evidence.”

But in the end, it didn’t matter, because there wasn’t any. There were only those same words sent over and over again from person to person: “AJ is dead.”

My relationship with AJ was always somewhere between friendly and flirtatious, and it reached an apex the summer before we became seniors in high school when we watched a lot of movies, kissed in a truck; I even had dinner with his parents. Maybe for a second we almost were, and then we weren’t. But that was okay; our relationship had always been fluid and easy. I trusted AJ. Even though I knew he liked drugs, and would often do them at parties, I never worried that he’d take things too far. He once told me that he would never do heroin “because I know I’d like it too much.”

But of course that wasn’t what happened. Fifty thousand Americans died from drug overdoses in 2016, and AJ was one of them. As soon as Fergus texted me the news I wanted to call him to find out how AJ had gotten involved with opioids. I wanted to know whether everybody else was aware of his drug problem and I was just in the dark. I wanted to understand how in the world this could have happened.

But Fergus lived in Canada and didn’t have a phone plan. It would cost him a fortune to talk on the telephone. I realize how irrational that sounds—Your friend died and you were concerned with phone plans? Or: What about Skype? Maybe it was also easier not to call. Maybe I appreciated the distance that technology gave us. I knew that a call would reflect my own shock and sadness back at me, and I didn’t want to stare at someone through a screen who I knew felt as hollow as I did.

And calling would also have made it real, as though I’d killed him. He wasn’t really dead yet. Not if I let the internet stand between me and his death.

After he died, I was alone in Manhattan, texting people and reading Facebook messages filled with condolences. I found out about the date of his funeral in a Facebook post from his mom. So while all of this public grief was unfolding online, each of us was experiencing it alone, tucked away in our separate corners of the world.

Later I got a message that AJ had “liked” one of my photos, but in fact his mother had taken over his Facebook page and it was no longer him, though it seemed to be. I still get the occasional notification that AJ has posted something on his wall or that he is online. This always feels existentially wrong, a dead person spending time making Facebook posts.

The first time I felt genuinely better after his death was when I flew home to L.A. for the funeral. I spent the whole weekend in a cluster of friends, and was alone for no more than two hours the entire time. We really “shared” memories and stories. We held one another. We cried. We also went go-cart racing and ate garlic fries. We existed together in a way that was impossible over social media. We couldn’t plan what to say or how to express ourselves, as you can in online forums, and I think we suffered less because of it. We got to experience the honesty and relief of laying our grief bare to one another.

And, perhaps most importantly, we could all see, plainly, that AJ was not there.

Send A Letter To the Editors