According to some viewers, Ajlan Gharem’s “Paradise Has Many Gates” depicts a mosque as a cage. Photo courtesy of the artist and Gharem Studio.

When I first saw Ajlan Gharem’s video, “Paradise Has Many Gates,” at an art studio in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, I was amazed.

It opens with a small single-story structure made of chain-link fence standing alone in a flat expanse of sand, crowned by a small dome and a gold crescent moon. A minaret rises above one corner of the building, while a semicircular niche in one wall marks the direction of Mecca. When the call to prayer sounds, a group of men and boys enter. They kneel to pray; then stand and line up against one of the chain link walls, grasping it with their hands and facing directly into the camera. Two men in orange jumpsuits sit in a corner of the building as the sun sets. When the “prayer service” is over, the green lights of the minaret flicker off, leaving only the blackness of the desert night.

The video raised many questions for me: Was Gharem equating mosques with prisons? Was he suggesting that conservative forms of Islam like those supported by the Saudi government confined people in cages of hatred and violence? Or, as one Saudi cleric suggested, had he constructed a beautiful, open-air mosque in an act of great piety and devotion?

It is this uncertainty of the art’s meaning that makes it both powerful—and possible.

Saudi Arabia’s vibrant contemporary art scene will surprise many Americans because its very existence contradicts stereotypes of the country as a breeding ground for terrorists and as an ultraconservative theocracy of rich sheikhs in white robes and oppressed women in black veils. A close look at the work of some of the best young Saudi artists provides us with more nuanced and complex images of a country I’ve been fortunate to visit twice in order to conduct research on Saudi art and Saudi culture more generally.

“Modern art is booming here, ” the director of an art gallery in Jeddah told me when I visited that city on the Red Sea coast in 2016. Drawing inspiration from many different sources—Arabic calligraphy, traditional Islamic art, European high art, and American popular culture—Saudi artists are producing street art, pop art, installation art, performance art, and conceptual art. New art galleries have opened in Dhahran, Jeddah, and even in Riyadh, one of the most conservative cities in the kingdom.

Any attempt to understand contemporary Saudi reality must begin by recognizing that it is not the inevitable product of some immutable form of Islam or a timeless version of “Arab culture.” Rather, Saudi Arabia is the result of relatively recent historical and political events. Among these: the development of its vast oil reserves in the 1960s (which produced previously inconceivable wealth); the 1979 Iranian revolution and, in that same year, the violent takeover of the Holy Mosque in Mecca by Wahhabi fundamentalists (which forced the royal family to reverse its policies of cultural liberalization in order to placate conservatives); and the September 11, 2001 attacks on the World Trade Center in New York, and the controversial American wars in Afghanistan and Iraq that followed (which posed a challenge to the kingdom’s pro-American foreign policy).

The Saudi government’s response to these challenges—which threatened the regime by destabilizing Saudi society—has been a precarious balancing act. The Saudi royal family seeks to satisfy conservative religious clerics and their followers on the one hand, and more liberal, reform-minded segments of the population, on the other.

Now, Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman has emerged as the de facto ruler of the country, the power behind the throne of his father King Salman. He has adopted new and more aggressive domestic programs, with the goal of loosening the grip that conservative Wahhabi Islam has held on the country since 1979. He recently announced new policies that will allow women to play a larger role in society and diversify the economy by reducing the dependence on oil. But in a nod to conservative forces, he has initiated a more belligerent foreign policy by boycotting Qatar, interfering in the internal affairs of Lebanon, and conducting an increasingly violent war in Yemen. (Other components of Mohammad bin Salman’s long-term plan for the transformation of Saudi society can be seen in his ambitious document Saudi 2030.)

Arwa Al Neami’s “Never Never Land” documents “family night” at an amusement park in Abha. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Among the themes being explored by contemporary artists is the role of women in Saudi society, in particular the consequences of the ban on women driving, which is scheduled to be lifted in June 2018. Powerful examples of this work include Arwa Al Neami’s documentary photographs and videos entitled “Never Never Land,” which show Saudi women enjoying “family night” at an amusement park in Abha, a conservative city in the mountainous southwest. The most striking images depict young Saudi women dressed in long black flowing abayas driving brightly colored red, yellow, blue, and green bumper cars a smooth, black floor.

The title, “Never Never Land,” is not just a reference to the fantasy of eternal childhood imagined by J. M. Barrie in Peter Pan. It also refers to the signs at the entrances to the amusement park rides, reminding women that, “it is strictly prohibited to carelessly lift the abaya and expose your trousers, or to scream during the rides.” “Never Never Land” evokes both an imaginary place where dreams come true, and the very real Saudi Arabia, where women are met with constant messages about what they can never, never do: marry or divorce, open a bank account or start a business, attend a university, or travel abroad without the permission of their male guardian.

Al Neami’s portraits of Saudi women enjoying themselves driving even as they conform to the rules of their society evoke a bittersweet combination of humor, irony, and pathos. Al Neami has written that with “Never Never Land” she wanted to take her viewers with her “to live and feel what it is like for women in the theme park with all its fun and its restrictions.” As Al Neami told me, when we spoke in 2016, “Saudi women have a lot of fun, even though they are subject to social control.”

Ahmed Mater’s “Evolution of Man” shows Saudi Arabia’s complex relationship with its national treasure, oil. Image courtesy of the artist and Pharan Studio.

Other Saudi artists have focused on their country’s immense oil wealth, which has made Saudi Arabia one of the world’s richest countries. Ahmed Mater’s “Evolution of Man” explores his country’s complex relationship with this “national treasure” as both a blessing (bringing tremendous affluence) and a curse (contributing to extreme inequality, authoritarian government, and violent conflict).

“Evolution of Man” consists of five jet black rectangular light boxes hanging next to one another. Each displays a slightly different X-ray illuminated from behind by a bright blue light. The X-rays morph from a sharply outlined gasoline pump at one end, to the skeletal image of a man holding a pistol to his head at the other. In the middle three images, the nozzle of the gas pump gradually turns into a human hand holding a pistol, while the body of the gas pump grows progressively more irregular and curved, until it becomes the X-ray of a human head and torso.

Mater, who has called himself “the son of this strange and scary oil civilization,” discussed “Evolution of Man” with me in his studio in Jeddah. Mater recognizes that his work lies on what he calls “the red line of censorship.” And he knows precisely where that red line is and how it moves.

“When I produced [the piece] in 2008 or 9, it wasn’t easy to show it inside Saudi Arabia. Now I can see they like it more; now I can show it. As the era of big oil comes to an end … my message becomes more acceptable. In a post-oil economy, this work is less controversial. I’m talking about how this kind of economy, this oil-dependent life, is becoming very dangerous. Not just in this country; it’s a worldwide message.”

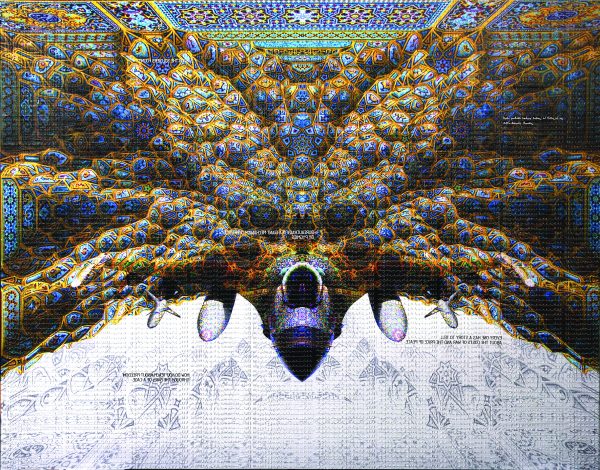

Abdulnasser Gharem’s “Ricochet” combines images of a jet fighter and traditional Islamic architecture. Image courtesy of the artist and Gharem studio.

The impact of war and violence is another area that Saudi artists are exploring. Abdulnasser Gharem, one of his country’s best-known artists, grew up in the southwestern corner of Saudi Arabia near the base used by the Saudi Air Force to launch bombing runs against Houthi rebels in nearby Yemen. He also went to secondary school with two of the Saudis who participated in the September 11 attack on the World Trade Center, and he served for 20 years as an officer in the Saudi army at a post on the Saudi-Yemeni border.

“Ricochet,” one of Gharem’s most powerful works, presents a frightening image of a jet fighter that emerges like an avenging fury from a turbulent cloud—a cloud of swirling turquoise and gold air currents that eerily evoke the small vaults and domes of traditional Islamic architecture.

The precise relationship between the fighter jet and the mosque is ambiguous. Is the mosque being transformed into a jet fighter? Is the jet coming from the mosque? Has it just flown through (and destroyed) the mosque? Standing in front of “Ricochet,” which was on display in an American gallery, a Saudi visitor observed sadly: “Our culture is not producing beautiful mosques anymore; we are producing jet fighters. Instead of spreading religion and peace, we are spreading terror and war.”

With powerful works like these, contemporary Saudi artists are providing a bridge between our world and theirs. As their art becomes accessible to Western viewers at galleries in Venice, London, New York, and Los Angeles, these artists, as individuals with distinct political voices, are able to convey their insider perspectives on a country that has been defined by the stereotypes of outsiders. At its best, this art transcends, without denying, the differences between Saudis and the outside world, and those within Saudi society itself.

Send A Letter To the Editors