The command center at the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency, shown here, was the source of a mistakenly sent alert warning of an incoming ballistic missile on January 13, 2018. Photo courtesy of Caleb Jones/Associated Press.

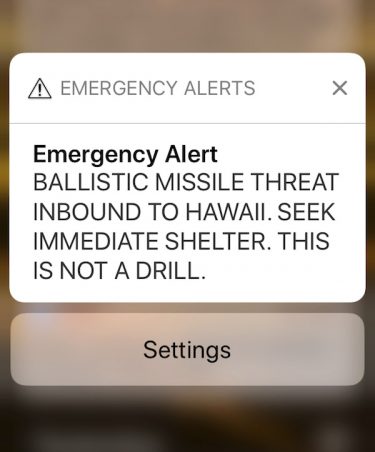

Shortly after 8 a.m. on January 13, 2018, the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency sent out a chilling alert to residents across the state of Hawaii: “BALLISTIC MISSILE THREAT INBOUND TO HAWAII. SEEK IMMEDIATE SHELTER. THIS IS NOT A DRILL.”

Thousands of frightened people flocked to shelters; some even climbed down manholes to save themselves. Hawaii State Representative Matthew LoPresti told CNN: “I was sitting in the bathtub with my children, saying our prayers.” It was not until 38 minutes later that a second message made it clear that that the first had been a false alarm.

Such episodes are not new. Since the advent of mass communications, similar scares have taken place. From intentional hoaxes to accidental alerts, we have become susceptible to reports of terrifying events that never come to pass.

Canadian philosopher and media scholar Marshall McLuhan famously observed that we all live in a global village. Where it once took months to relay news from the other side of the world, it now takes less than a second. The problem is, with so many people now reliant on the internet and mobile phones, the potential for technology-driven hoaxes, panics, and scares has never been greater. And such events, while usually short-lived, have tremendous power to wreak widespread fear and chaos.

The most famous example of mass panic in response to an announcement is the 1938 “War of the Worlds” radio drama produced by Orson Welles at WABC’s studios in New York City. Broadcast across the United States and in parts of Canada, the play narrated a fictitious Martian invasion of the New York-New Jersey metropolitan area. In his bestselling book The Invasion From Mars, American psychologist Hadley Cantril wrote that of the estimated 6 million listeners, about 1.5 million were frightened or panicked.

A smartphone displaying a false incoming ballistic missile emergency alert, sent Jan. 13, 2018. Image courtesy of Caleb Jones/Associated Press.

While contemporary sociologists who have re-examined the episode believe that the number of those who panicked was much smaller, no doubt many were frightened. Some people living near the epicenter of the play—tiny Grover’s Mill, New Jersey—tried to flee the Martian “gas raids” and heat rays.” During the hour-long broadcast, The New York Times fielded 875 phone calls about the broadcast. Curiously, Cantril found that about one-fifth of listeners thought that America was under attack by a foreign power—most likely Germany, using advanced weapons. Historical context often plays a major role in shaping the mindset of listeners.

While perhaps the best-known incident, the 1938 broadcast did not have the most serious consequences. That distinction goes to another radio play, broadcast in 1949, that caused pandemonium in Quito, Ecuador. That highly realistic production mentioned real people and places, and included impersonations of government leaders. A correspondent for The New York Times in Quito at the time described a tumultuous scene as the drama “drove most of the population of Quito into the streets” to escape the Martian “gas raids.”

After realizing that the broadcast was a play, an enraged mob marched on the radio station, surrounded the building, and burned it to the ground. At least 20 died in the rioting and chaos. Authorities had trouble restoring order, as most of the police and military had been sent to the nearby town of Cotocallao to repel the Martians.

These “War of the Worlds” broadcasts were not the first to provoke false alarms. One of the earliest recorded scares occurred in the United Kingdom in 1926, when the BBC reported that the government was under siege and could fall amid a bloody uprising by disgruntled workers. In reality, the streets of London were calm; people had only been listening to a radio play airing on the regularly scheduled Saturday evening radio program.

The BBC broadcast announcements throughout the evening, apologizing and reassuring listeners. But the story was plausible, given deep tensions with labor unions at the time. And, four months after the broadcast, a historic General Workers Strike rocked the government, as 1.5 million workers took to the streets over 10 days to call for higher wages and better working conditions.

Decades later, on March 20, 1983, hundreds of Americans were frightened by a broadcast of the NBC Sunday Night Movie Special Bulletin, about news coverage of a group of terrorists who were threatening to detonate a nuclear bomb in South Carolina. The program began like any other Sunday night movie but was quickly “interrupted” by breaking news bulletins from well-known news outlets such as Reuters and the Associated Press, showing scenes of devastation. The film even recreated a White House press briefing. Special bulletins throughout the show were interrupted by “live feeds” from the terrorists. Conveniently, a reporter and a cameraman happened to be among the “hostages.”

The realism of the special broadcast was instrumental in creating the panic. The fictional NBC affiliate broadcasting the siege in Charleston, WPIV, was similar to the real affiliate, WCIV. The real-world WCIV-TV received 250 calls; others rang the police. WDAF in Kansas City fielded 37 calls. At San Francisco’s KRON-TV, 50 calls were logged in the first 30 minutes. One woman was so convinced that she called to complain that too much air time was being given to the terrorists. The program began with an advisory that what viewers were about to see was a “realistic depiction of fictional events” but was not actually happening. Unfortunately, the next advisory did not run until 15 minutes later. The movie won an Emmy, but across the country viewers mistook it for a live news coverage and thought a nuclear catastrophe was imminent.

It wouldn’t be the last nuke scare. On November 9, 1982, WSSR-FM in Springfield, Illinois, reported that there had been an accident at a nearby nuclear power plant. The program began by claiming “that a nuclear cloud was headed for Springfield.” Concerned residents immediately deluged police with phone calls, prompting the station, which was operated by Sangamon State University, to pull the plug on the half-hour drama after just two and a half minutes. The Illinois Emergency Services and Disaster Agency was not amused. Director Chuck Jones said: “I’m still shocked that someone out at that station let that get on the air.” The nuclear power plant depicted in the program was located 25 miles northeast of the city, and while it was not operating at the time, people didn’t have any way of knowing this.

While many false alarms have apparently been unintentional, there are egregious examples of deliberate attempts to cause widespread fear. On January 29, 1991, DJ John Ulett of radio station KSHE-FM in Crestwood, Missouri, decided to protest America’s involvement in the Persian Gulf War by airing the following announcement: “Attention, attention. This is an official civil defense warning. This is not a test. The United States is under nuclear attack.” Worried listeners flooded the station with phone calls. While Ulett’s statement did not trigger a mass panic, the Federal Communications Commission fined the station $25,000. Ulett was suspended but managed to save his job.

Poorly timed jokes have also triggered dramatic results. On August 11, 1984, just before his weekly radio address, President Ronald Reagan tested his microphone by saying: “My fellow Americans, I am pleased to tell you today that I’ve signed legislation that will outlaw Russia forever. We begin bombing in five minutes.” Americans didn’t panic, because the broadcasters knew he was joking, but the Russians, nervous at a time of considerable distrust between the two countries, placed their armed forces on standby.

Even fleeting scares can have long-term consequences. The 1938 Martian scare resulted in jammed phone lines. In Trenton, emergency services were knocked out for six hours. In Quito, damage from the rioting was estimated at $350,000—an enormous sum at the time.

In 1597, English philosopher Francis Bacon famously observed, “Knowledge is power.” But in today’s world, knowledge comes with risk. The most educated and technologically adept generation in the history of the world is also the most vulnerable.

Send A Letter To the Editors