Indentured Indian laborers, newly arrived in Trinidad. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

One Sunday morning in 1993, “Bushman,” “Spider,” “Tall Boy,” and “Crab Dog” were gathered at a rum shop in the Guyanese coastal village of Mahaica. The rainy season had driven these Afro-Guyanese diamond miners out of the interior, and they had settled down for a companionable drinking session. They were joined by Terry Roopnaraine, an anthropologist gathering information for a study of gold and diamond mining. Spider, who was flush with the proceeds from a big strike, was treating the others from his earnings. Eventually, Bushman announced that he had killed an iguana the day before.

“So, let’s cook him,” the men declared.

Tall Boy, who worked as a cook out in the mining camps, persuaded the rum shop owner to let him use the kitchen in back. He softened onions in coconut oil while he slit the belly of the iguana, cleaned out its guts, and chopped up the carcass. After sprinkling a generous helping of curry powder over the onions, he threw the meat in the pot followed by a glug of cane spirit to counter its musty odor. He set a pot of rice to cook while the curry was simmering and the men drank yet more rum. When the food was ready, they eagerly wolfed it down and then sauntered off to doze away the afternoon.

The story of how a group of Afro-Guyanese diamond miners came to be making a bush-meat version of an Indian curry begins in 1627, when a band of 50 British men founded the colony of Barbados, on the uninhabited island.

These colonists experimented with growing tobacco, cotton, ginger, and indigo as they sought to make their fortunes. But it was not until James Drax returned from a visit to Portuguese Brazil with sugar cane in 1640 that the settlers found the cash crop of their dreams. An acre of land planted with cane earned Drax four times more than an acre planted with tobacco. Within a decade, every scrap of land on the 169-square-mile island was planted with sugarcane, and Barbados became the wealthiest colony in the British Empire.

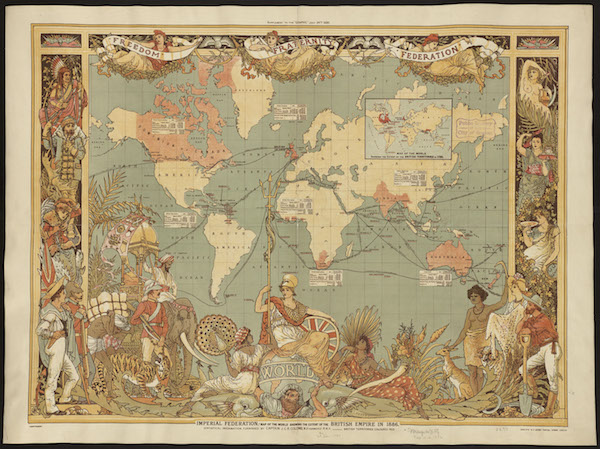

Imperial Federation map of the world showing the extent of the British Empire in 1886. Image courtesy of Boston Public LIbrary/Flickr.

The planters initially employed white indentured laborers and convicts to do the back-breaking and dangerous work of cultivating and processing the sugar cane. In Britain under Oliver Cromwell, to be “Barbadosed” was to be transported into servitude on the West Indian plantations. But white men were gradually replaced by West African slaves, as English ships tapped into the trans-Atlantic slave trade already established by the Portuguese to supply workers for their South American sugar plantations.

At the end of the 18th century, on a tour of the West Indies, which included Barbados, ship’s purser Aaron Thomas was so shocked by the conditions in which the slaves lived and worked that he wrote in his sea diary, “I never more will drink Sugar in my Tea, for it is nothing but Negroe’s blood.”

The British dissolved most of the sugar they consumed in tea. Over the 100 years after Drax sent home his first consignment, sugar poured into Britain in unprecedented quantities and its consumption rose in tandem with that of tea. The price of both commodities fell until even the poorest could afford them. A late 18th-century survey found that rural laborers spent as much as 10 percent of their annual income on tea and sugar; while Friedrich Engels noticed that tea was “quite indispensable” to the inhabitants of Manchester’s slums.

Social commentators condemned the poor for wasting their money on these “luxuries.” But tea-drinking was a symptom not of extravagance but of workers’ impoverishment. Rising food and fuel prices meant that they could barely afford to cook a warm meal let alone simmer the wort to brew their own beer. As a consequence, they turned for sustenance to shop-bought bread washed down with tea sweet enough to provide them with energy as well as the illusion that they were eating a warm meal. One family of ironworkers dissolved four pounds of sugar—enough to fill 10 teacups—in their weekly half-pound of tea. Britain’s Industrial Revolution was fueled by tea and sugar.

During the Napoleonic Wars (1803−15), Britain acquired two new sugar-producing colonies: French Mauritius and British Guiana. But when slavery was abolished in 1838, more than half the West African slaves turned their backs on the sugar plantations, resulting in a drastic fall in production.

The planters searched for a replacement workforce and found it in India, where a growing number of impoverished laborers were seeking work. Britain’s Industrial Revolution had sent India’s economy into turmoil. In the 1820s the British imposed protective tariffs closing the British market to Indian textiles; instead, cheap, machine-made Manchester cottons flooded into India. Millions of Indian artisans went out of business and joined the growing number of landless laborers pushed off the land by debt.

And so the resources of the British Empire, which had been channeled into the slave trade, were redirected into moving hundreds of thousands of Indians to work on plantations around the globe. Between 1838 and 1916, about 240,000 Indians were taken to British Guiana.

This was how curry came to the northern coast of South America and the country now called Guyana.

Indian indentured laborers were given rations of rice, lentils, coconut oil, sugar, salt, and curry powder, all of which allowed them to make a semblance of Indian meals. The one ingredient that they would not have used in India was curry powder. This was a British invention. The Victorians usually would mix cayenne pepper, cumin, coriander, lots of turmeric (Indians tended to be more sparing in their use of this spice), and fenugreek, which was a commonly used spice around Madras, where the first curry powder factories were set up.

When the British had first settled in India as merchants and traders they had loved Indian food, and brought cooks and recipes back to Britain with them when they retired. The first cookbook to include a recipe for “how to make a curry the India way” was Hannah Glasse’s The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy published in 1747. In Indian kitchens the spices were freshly roasted and ground each morning before they were added to the dishes at different stages in the cooking process. Glasse’s recipe attempted to replicate Indian practice by instructing the cook to first roast the spices on a shovel over the fire before beating them to a powder.

However, as the British grew accustomed to making Indian food, they took shortcuts, and over time Victorian cooks transformed curries into spicy casseroles. An essential element in this transformation was the use of standardized, pre-mixed curry powders that became commercially available in the 1780s. The Victorians would use a spoonful of curry powder to curry anything from periwinkles to sheep’s trotters. British curries became unrecognizable to Indian visitors who were dismayed when they were confronted with these hashes “flavoured with turmeric and cayenne.”

Even though it was Indian indentured laborers who first taught the Africans in Guyana how to cook curry, Indian food there was diminished by the forces of Empire. Limited rations meant that the indentured laborers struggled to replicate Indian home cooking. There were only two types of pea available to make dhal and everything had to be cooked in coconut oil. The biggest handicap was that, instead of the plethora of different spices and herbs available to an Indian cook, the laborers were only given a pre-mixed curry powder. This meant that, in Guyana, the panoply of different styles and types of dish were replaced by one simplified version of a curry. Although there are distinctively Guyanese combinations, such as shrimp and pumpkin, Indo-Guyanese dishes are all variations on one theme.

The meal of iguana curry eaten by a group of Afro-Guyanese diamond miners on a Sunday morning in 1993 carries within it the story of how Africans and Indians were brought to the Americas by the British craving for sweetness.

These two groups of arrivals and their progeny developed different relationships with their new homeland. The Indo-Guyanese tended to stay close to the coast within the orbit of the plantation world. Once freed from slavery, the Afro-Guyanese had made their way into the interior to tap rubber, and prospect for gold and diamonds. Here they interacted with the Amerindians who taught them how to hunt and cook the forest animals. And so the Africans applied the currying technique they had learned from their Indian neighbors to bush meat.

The British Empire was a powerful force for spreading new foods and new ways of eating throughout the globe. And yet it was also a powerful force for homogenization. Through the collisions of history, middle-class British housewives and South American descendants of African slaves both ended up eating a similar version of Indian food: a curry of peculiar meats, made with curry powder.

Send A Letter To the Editors