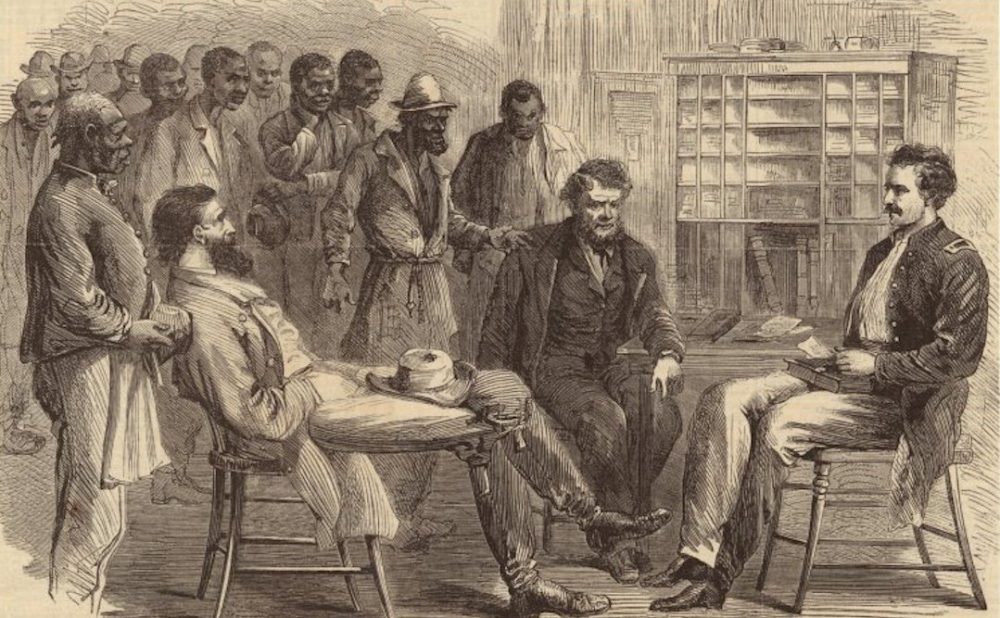

Illustration from Harper’s Weekly of the Office of the Freedmen’s Bureau, Memphis, Tennessee. (1866). Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

After the Civil War, the four million black Americans who had been enslaved encountered numerous new forms of authority, most of which seemed to promise protection and support rather than exploitation and abuse: teachers in schools, doctors in hospitals, employers who paid wages, the U.S. Army, municipal police, and a federal agency known as the Freedmen’s Bureau.

Becoming free involved figuring out the inconsistent rules and behaviors of these new authorities. The government, even as it sponsored freedom, was not always a just actor—nowhere more egregiously than in the case of vagrancy laws, which were grounded in the racial prejudice that black people are criminals.

On the surface, vagrancy has nothing to do with race. The homeless and the jobless come in all colors. And the idea of criminalizing people who are “wandering about without proper means of livelihood” (as the Oxford English Dictionary puts it) has been around since medieval England. But, in the Civil War-era United States, that described nearly everyone who had been a slave.

Vagabondage may sound like freedom to a hobo singing “Big Rock Candy Mountain,” but to the upstanding citizen it sounds like crime. In the wake of the Civil War, African Americans found themselves caught amid the same kind of dissonance: What freedom meant to them—unfettered mobility, access to education, and the security of their families—was not what it meant to white people.

One of the testing grounds for the post-war racial order was Memphis, a Southern city that fell to federal forces only about a year into the Civil War, in June 1862. The city became a magnet for African Americans in the surrounding countryside, who first came behind Union lines to flee slavery. But as the war went on, they came seeking jobs, reunion with loved ones, and a sense of community. By the end of the war, Memphis’s black population had grown from 3,000 to 20,000.

The growth of Memphis’s free black population meant that west Tennessee plantations were proportionally emptied—to the dismay of cotton planters who needed laborers in their fields. Vagrancy laws provided a convenient solution to the labor shortage: Memphis blacks who could not prove gainful employment in the city were presumed guilty of vagrancy and subject to arrest and impressment into the agricultural labor force. They were brought back onto the plantations, and forced to sign labor contracts.

Using vagrancy laws to enforce “slavery by another name” was an innovation of the post-war South, but the way had been paved long before. In the decades leading up to the Civil War, the figure of the vagrant had become distinctly entangled with race, and rhetoric about vagrancy had bled into national debate about emancipation.

In parts of the South, where modest populations of free blacks stood outside the purview of slave codes, vagrancy laws had restrained the movements and behaviors of those African Americans who weren’t enslaved. In free states along the border, like Pennsylvania, rising numbers of fugitives from slavery found themselves ensnared in vagrancy’s legal web.

By the 1860s, with the wholesale abolition of slavery appearing on the horizon, standard rhetoric about vagrants merged with white anxieties about labor markets swamped by a wave of freed slaves. Some whites believed blacks were inherently lazy and would not work if not forced to; even many abolitionists worried that slavery had so brutalized African Americans that they would be incapable of self-sufficiency.

“Worthless” and “idle”—two of the adjectives that most commonly modified the word “vagrants” in the antebellum United States—were ill-suited to describe enslaved people, who had tremendous market value as commodities and were forced to labor unceasingly. But once freed from slavery, black people were slapped with all the standard labels for vagrants.

In Memphis, the convergence was especially pronounced. The Freedmen’s Bureau, which was created in March 1865 to assist former slaves in their transition to freedom, instead wielded vagrancy statutes to do the bidding of white planters. The first superintendent of the Freedmen’s Bureau office in the city was ostensibly sympathetic with former slaves—he loudly deplored “injustice to the Freed people”—but even he said he was “determined that the Freed people shall not become a worthless, lazy set of vagrants living in vice and idleness.” That superintendent’s successor, Nathan Dudley, wrote that Memphis had a “surplus population of at least six thousand colored persons [who] are lazy, worthless vagrants.”

So it was that the Freedmen’s Bureau—the part of the federal government charged by Congress and Abraham Lincoln to ensure the integrity of black freedom—could authorize patrols that were arresting black Memphians indiscriminately and delivering them up to white employers for bounties ranging from a dollar to five dollars “per head.”

As Anthony Motley, an African-American barber, put it in a letter to Freedmen’s Bureau commissioner Clinton Fisk, “the great Slave trade Seems To be Revived in Memphis.”

One of the leading voices of black protest was another barber named Warner Madison. Though barely educated, he was more literate than most African-American Memphians, so he penned multiple letters of protest, including some on behalf of a committee of citizens. In a letter to Fisk he began by describing what was going on: “they go around and arrest all they Can find regardless whether they are employed or not Just ask if you dont want to go with Mr who ever it May be they dont find out whether you want to go or not atall they Make out the agreement sell you for the price that the Man give them.” Then Madison narrated an instance of a young African-American man being taken away “By the point of the baynet” at the direction of a Freedmen’s Bureau agent.

As his letter rose to a pitched fury, Madison began to punctuate almost every word, as if stabbing at the paper with his pen: “i think, it is, one of the most. obnoxious. and foul, and, mean. thing. that exsist on, anny. part. of. the. Beauraur. Why My Childrem has, to, get. passes, now. to, go, to. schooll.”

Madison’s climactic complaint—that black children on their way to school were being considered “vagrants”—echoed in other Memphians’ protests. Anthony Motley drove home the same point in his own letter to Fisk: “Children going to School With there arms full of Book have Been arrested and Put up in Pens Like Sheep.”

Fisk replied politely but made no mention of these schoolchildren. When Nathan Dudley of the Freedmen’s Bureau investigated these and other claims and issued a report to his superior, he concluded, “I can find no evidence whatever that School children, with Books in their hands have been arrested, except in two or three cases, which was done by a misconstruction of the order.”

It is a curious turn of logic to say that when something is done two or three times, however inappropriately, there is “no evidence whatever” of its having happened. But that would not be the last time an egregious racial injustice was written off as an anomaly, rather than seen as a red flag. It would take 100 years and a great protest movement before U.S. courts acknowledged vagrancy laws’ enormous potential for abuse. During the Civil Rights era, most of them were invalidated.

What hasn’t disappeared is the cultural and legal association of blackness with criminality. In Memphis in 1865, the apparent innocence of being a school-bound child didn’t trump the presumptive guilt of being black. And in Memphis as recently as 2012, African-American youth were more likely to be incarcerated than white youth with the same criminal records—among other racial inequities severe enough to warrant intervention by the U.S. Department of Justice. And even as Memphis marks the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King’s assassination this month, its juvenile court will remain under federal oversight.

Less strict oversight, though: The current administration backed off last summer. This inconsistent defense of our racial justice remains yet another legacy of the Civil War era.

Send A Letter To the Editors