Theodore Roosevelt and his Big Stick in the Caribbean (1904). Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

A president’s career can extend well beyond his death, as family, friends, and fans work tirelessly to maintain his legacy and image.

For roughly 10 years, I have studied the legacy of the 26th president, Theodore Roosevelt. Even after a decade, I continue to be astounded by how regularly Roosevelt is invoked in politics and beyond.

Today, TR is ubiquitous. If you follow sports, you may have seen Teddy Goalsevelt, the self-appointed mascot for Team USA soccer who ran for FIFA president in 2016. Or you may have watched the giant-headed Roosevelt who rarely wins the Presidents’ Race at Washington Nationals baseball games. If you enjoy the cinema, you will likely recall Robin Williams as Roosevelt in the Night at the Museum trilogy, or might know that a biopic starring Leonardo DiCaprio as Roosevelt is slated for production.

In politics, Roosevelt has become the rare figure popular with both left and right. Vice President Mike Pence recently compared his boss Donald Trump to Roosevelt; in 2016, candidate Hillary Clinton named the Rough Rider as her political lodestar. Environmentalists celebrate Roosevelt as the founding father of conservation and a wilderness warrior, and small business interests celebrate his battles against large corporations.

And more than a century after he was shot in Milwaukee during the 1912 presidential campaign, Roosevelt remains a target; last year, his statue in front of the Museum of Natural History in New York was splattered in red paint in protest of its symbolic relationship to white supremacy, among other things.

Roosevelt’s high profile is no mere accident of history. Shortly after Roosevelt’s death, two memorial associations organized and worked to perpetuate his legacy.

One of these organizations sought to tie Roosevelt to the politics of the early 20th century, and cast him as a national icon of Americanism. At that time, Americanism stood for patriotism and civic-mindedness, as well as anti-communism and anti-immigration. This ideology helped Republicans win back the White House in 1920, but it also galvanized the first Red Scare.

The second memorial organization rejected the political approach to commemoration, choosing to represent Roosevelt’s legacy in artistic, creative, and utilitarian forms, including monuments, films, artwork, and by applying the Roosevelt name to bridges and buildings. Of course, some of these activities had implicit political angles, but they generally avoided association with overt causes, in favor of historical commemoration. When it came to fundraising, the apolitical organization raised 10 times as much income as the political one, and within ten years the two organizations folded into a single memorial association that abandoned political interpretations. Roosevelt became bipartisan and polygonal.

This is not to say Roosevelt’s legacy lost all meaning. Quite the opposite; our perception of Roosevelt has endured a number of declines and revivals. And, through the rounds of historical revision and re-revision, he has maintained certain characteristics.

His civic-minded Americanism endures, as does his record as a conservationist and a progressive. Roosevelt still evokes an image of an American cowboy, a preacher of righteousness, and a leading intellectual.

Most interestingly, these elements of his legacy are not mutually exclusive. Invoking one does not require us to exclude another. For example, Barack Obama promoted the Affordable Care Act in 2010 by memorializing Roosevelt’s advocacy for national healthcare in 1911. Obama could recall Roosevelt’s progressivism while avoiding the Bull Moose’s mixed record on race relations or his support of American imperialism. In short, commemorators can take from Roosevelt what they want and, consequently, his legacy grows ever more complex and elastic.

The upcoming centenary of Roosevelt’s death in January 2019 offers us an opportunity to understand more about how presidential legacies are shaped by successive generations. Images of former presidents come from various sources, and because they can act as a powerful emblem for any cause, their images proliferate without much scrutiny.

Politicians are well aware of this. Sarah Palin, a right-wing Republican, co-opted the legacy of Democrat Harry Truman in her 2008 vice-presidential nomination speech, and Barack Obama had a penchant for invoking Ronald Reagan. In a political swamp full of alligators, summoning the ghosts of dead presidents is relatively safe ground.

Likewise, commercial advertisers take great liberty with the past. Beer and whiskey producers have long used presidents as brand ambassadors (Old Hickory bourbon and Budweiser are good examples). Automobile companies have named vehicles for Washington, Monroe, Lincoln, Grant, Cleveland, and Roosevelt.

These contemporary invocations remind us of the real value of legacy, however it might be interpreted. The past has meaning for the present, and that meaning can be translated into advantage. Truth is not the highest value in the contest between presidential ghosts.

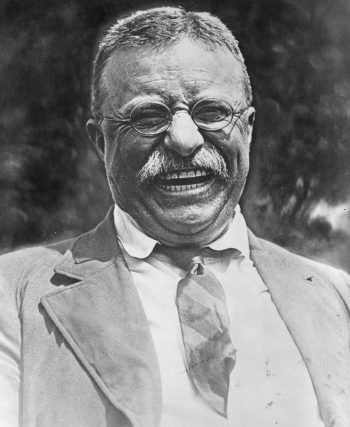

Happy Warrior: Teddy Roosevelt in 1919, the last year of his life. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Despite being the subject of scholarly historical biographies that document their lives with precision and care, American presidents are dogged by half-truths, myths, and arbitrary citations in public memory. At a time when our political climate is referred to as “post-truth,” and a celebrity tycoon who has mastered the art of self-promotion sits in the Oval Office, it is worth reflecting on how these legacies are produced.

If, as philosopher Williams James once said, “The use of a life is to spend it for something that outlasts it,” the former American presidents have lived boundlessly productive lives, with legacies that far outlast their tenure. But because their legacies are produced by successive generations, they often tell us more about the agents of commemoration than the men who sat behind the Resolute Desk.

Examining presidential legacies helps us solve a historical problem: It allows us to see who shapes our perceptions of the past. Memorializers lay claim to historical narratives and create the illusion of public memory, invoking select elements of our shared past as shiny baubles to emulate and admire. So by understanding these myths, the mythmakers, and the motives of memorialization, we can see a laminated past with countless layers. The more myths and the more layers, the more insight we gain into the ways the past connects with the present, and the present with the future.

The “real” Theodore Roosevelt is lost to us. He is an imagined character, even to family. Theodore Roosevelt’s grandson Archie met his grandfather only once. Still, every time he visited Sagamore Hill—his grandfather’s home in Oyster Bay, Long Island—he sensed his ghost. Archie felt that TR’s spirit looked over the kids as they played. On numerous occasions Archie reflected on his grandfather’s likely expectations for his family and even attempted to model his life on that conception. “We knew him only as a ghost,” Archie related, “but what a merry, vital, and energetic ghost he was. And how much encouragement and strength he left behind to help us play the role Fate has assigned us for the rest of the century.”

Indeed, conjuring Roosevelt’s ghost gives us another means of observing the last century, a period of time that Roosevelt himself never saw. Because so many have invoked Roosevelt in the way Archie did, examining his legacy helps to illustrate the motives and judgements of those who remember the past. Theodore Roosevelt’s ghost continues to haunt public memory because we continue to conjure it. TR has been dead for a century, but we refuse to let him rest in peace, believing the use of his life can help us achieve our ends.

Send A Letter To the Editors