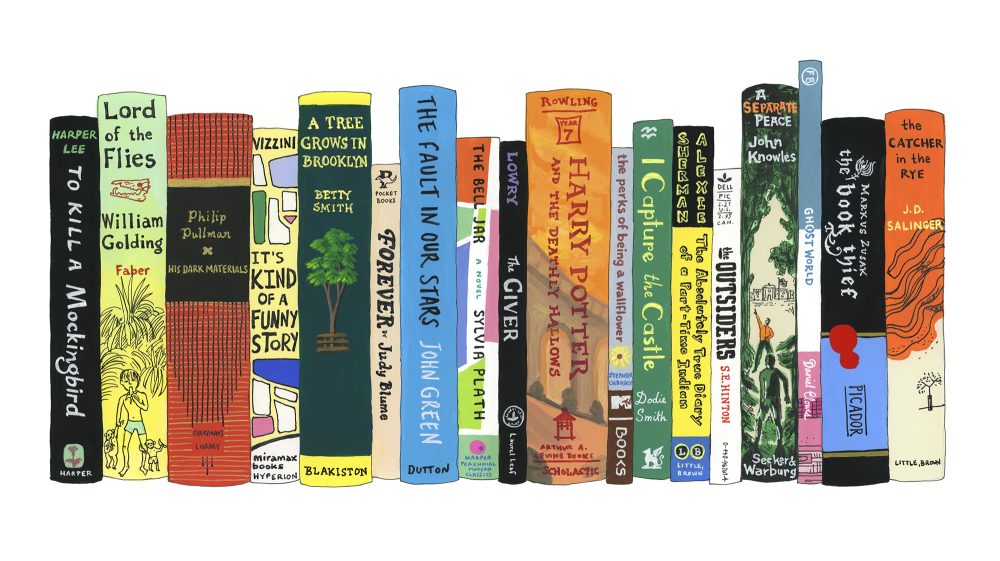

Ideal Bookshelf 651: Coming of Age. Art courtesy of Jane Mount/idealbookshelf.com.

Like jazz, the Broadway musical, and the foot-long hot dog, young adult literature is an American gift to the world, an innovative, groundbreaking genre that I’ve been following closely for more than 30 years. Targeted at readers 12 to 18 years old, it sprang into being near the end of the turbulent decade of the 1960s—in 1967, to be specific, a year that saw the publication of two seminal novels for young readers: S. E. Hinton’s The Outsiders and Robert Lipsyte’s The Contender.

Like jazz, the Broadway musical, and the foot-long hot dog, young adult literature is an American gift to the world, an innovative, groundbreaking genre that I’ve been following closely for more than 30 years. Targeted at readers 12 to 18 years old, it sprang into being near the end of the turbulent decade of the 1960s—in 1967, to be specific, a year that saw the publication of two seminal novels for young readers: S. E. Hinton’s The Outsiders and Robert Lipsyte’s The Contender.

Hinton and Lipsyte clearly were writing a new kind of novel for young adults—one of unsparing contemporary realism that met a need articulated by Hinton herself in a passionate article in The New York Times Book Review published on August 27, 1967. Here’s what she wrote:

Teenagers today want to read about teenagers today. The world is changing, yet the authors of books for teen-agers are still 15 years behind the times. In the fiction they write, romance is still the most popular theme with a horse and the girl who loved it coming in a close second. Nowhere is the drive-in social jungle mentioned. In short, where is the reality?

The answer, of course, was to be found in the pages of her novel. The Outsiders had a mean-streets setting and dealt with urban warfare between teenage gang members, dubbed, respectively, the Greasers and the Socs. Hinton’s mean streets were in her hometown of Tulsa, Oklahoma; those of her equally innovative fellow author Robert Lipsyte were in New York City. His 1967 novel The Contender featured one of the first protagonists of color to appear in young adult literature, the African-American teenager Alfred Brooks, who struggles to become a contender both in the boxing ring and in life.

Before these two novels, literature for 12- to 18-year-olds was about as realistic as a Norman Rockwell painting—almost universally set in small-town, white America and featuring teenagers whose biggest problem was finding a date for the senior prom. Such books were patronizingly called “junior novels” and were typically sweet-spirited romances, a genre that defined the 1940s and 1950s and featured books by the likes of Janet Lambert, Betty Cavanna, and Rosamond DuJardin, among others. Indeed, virtually all literature for young readers in those two nostalgia-inducing decades consisted of inconsequential, formulaic, genre fiction: not only romance but also science fiction, adventure tales, and novels about sports, cars, and careers.

Small wonder, then, that this newly hard-edged, truth-telling, realistic fiction filled such a need. Seemingly overnight, a new genre, young adult literature, sprang into being. Within two years, noteworthy novels such as Paul Zindel’s My Darling, My Hamburger and John Donovan’s I’ll Get There. It Better Be Worth the Trip had embraced real world considerations like abortion and homosexuality, respectively. In 1971, Hinton wrote about drug abuse in That Was Then. This Is Now and in 1973 Alice Childress joined her with A Hero Ain’t Nothin’ But a Sandwich, which told a story of heroin addiction.

And then came 1974, and the publication of one of the most important and influential novels in the history of young adult literature. Robert Cormier’s The Chocolate War was arguably the first young adult novel to trust teens with the sad truth that not all endings are happy ones. In this unforgettable book, arguably the first literary young adult novel, 17-year-old protagonist Jerry Renault steadfastly refuses to sell chocolates for his school—an act with dire consequences. Cormier took his readers into the dark heart of adolescent anxiety, and turned on the lights, revealing a bleak moral landscape. In The Chocolate War and 14 other novels that followed, Cormier continued to dare to disturb a too-comfortable universe by acknowledging, as he told an interviewer, that, “Adolescence is such a lacerating time that most of us carry the baggage of it with us all our lives.”

The cover for the Laurel Leaf Library paperback edition of The Outsiders. Image courtesy of Flickr.

Young adult literature, as we know it today, has been an exercise in evolution consonant with the evolution of the concept of the young adult itself. It hinges on the obvious fact that there could not be a young adult literature until there were “young adults,” something that didn’t happen until the late 1930s and early 1940s, when there emerged an American youth culture populated by kids newly called “teenagers.”

The word first appeared in print in the September 1941 issue of the magazine Popular Science Monthly. In earlier times, there had been—generally speaking—only two population segments in America: adults and children (the latter becoming adults when they entered the workforce, sometimes at as young as age 10). But in the 1930s and 1940s, driven by a drying-up of the job market during the Great Depression, record numbers of adolescents started attending high school. In 1939, 75 percent of 14- to 17-year-olds were enrolled in high school. A decade earlier only 50 percent had been.

Popular culture took note and teenagers quickly became a staple feature of radio and motion pictures, often presented as stereotypical figures of fun. Boys were depicted as socially awkward, blushing, stammering, and accident-prone, while girls were giggly and boy-crazy. Teenagers were also consumers, editors at the new Seventeen magazine saw in 1945, when they hired the research company Benson and Benson to conduct market research that showed that girls—and boys—now had money of their own to spend. As a result, the entertainment industries began creating radio programs and motion pictures targeted at teens, offerings like A Date with Judy, Meet Corliss Archer, and—for boys—The Roy Rogers Show, Hopalong Cassidy, and Gene Autry’s Melody Ranch. That quintessential teenager Mickey Rooney became a star of the Andy Hardy movies, while Deanna Durbin emoted for girls. Teenagers clearly were more innocent then–or so parents hoped.

Librarians first began calling teenagers “young adults” as early as the mid-1940s. In 1944, librarian Margaret Scoggin wrote a journal article introducing the term, and arguing that the group constituted a new service population. (Scoggin is remembered for her work in helping to establish the New York Public Library’s landmark Nathan Straus Branch for Children and Young People in 1940. The Branch became a template for other libraries that established service for young adults in the 1940s.) Thereafter, the two designations—“teenager” and “young adult”—were typically used interchangeably by librarians and educators. The practice of referring to “young adult” literature was formalized in 1957 when the American Library Association created its Young Adult Services Division, which focused librarians’ attention on how to serve this new population.

Book people were talking the talk in the 1940s and 1950s—but they had a teenage readership without a literature to match its evolving interests and its socioeconomic, emotional, and psychological needs. The genre fiction that was epidemic in the 1940s, 1950s, and early 1960s could not hope to do that—and the Young Adult Services Division recognized it. For several decades its annual lists of the best books for young adults included only books written for all adults, novels such as Isaac Asimov’s Fantastic Voyage (1966), Charles Portis’s True Grit (1968), and Ray Bradbury’s I Sing the Body Electric! (1969).

It wasn’t until 1970—three years after the formative publications of The Outsiders and The Contender—that a newly emergent, serious young adult literature was recognized. For the first time ever, an actual YA novel, written specifically for readers in that new, in-between segment of the population—Barbara Wersba’s Run Softly, Go Fast, about a teenage boy’s love-hate relationship with his father—was first admitted to the list.

And so, finally, young adults and their literature came together. The rest is a history that has seen young adult literature grow to become one of the most dynamic and influential segments of American publishing, one that is enjoyed not only by young adults but by adults as well. But that’s another story.

Send A Letter To the Editors