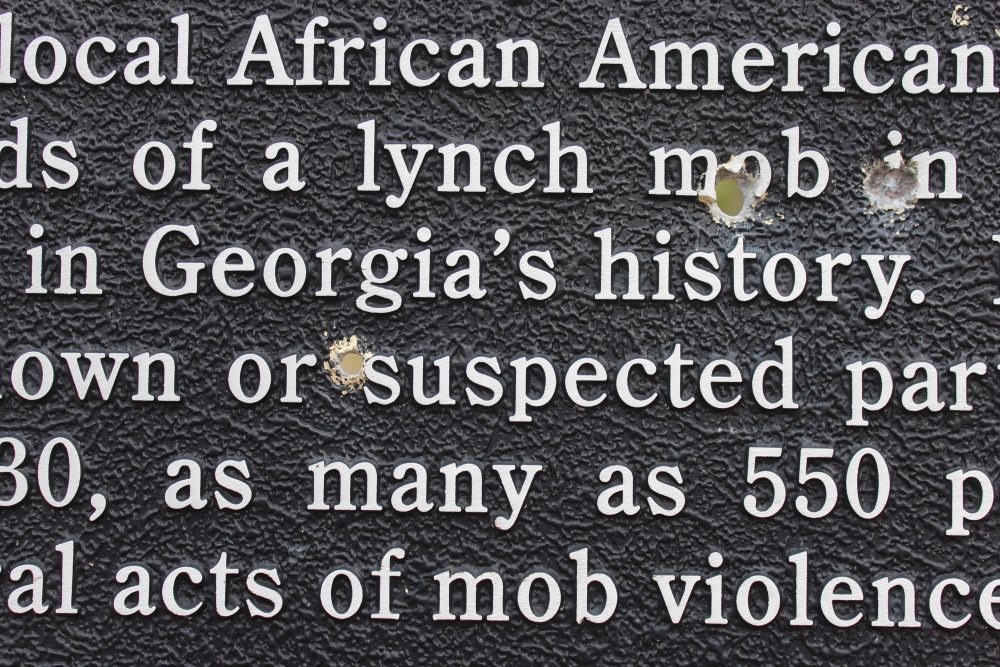

Bullet holes in the marker, which was erected in 2010. Photo courtesy of Julie Buckner Armstrong.

In Lowndes County, Georgia, by the side of State Road 122, stands a historical marker for “Mary Turner and the Lynching Rampage of 1918.” The metal marker describes in plain language a May 1918 spree of mob violence. After a white farmer was murdered, the mob killed at least 11 African Americans.

Mary Turner, the marker’s named victim, was eight months pregnant. The mob targeted her because she spoke out against the lynching of her husband Hayes. A crowd of several hundred watched the men hang, burn, and shoot Turner, then cut out her fetus and stomp it into the ground.

From 1998 to 2011, I researched and wrote a book about Mary Turner’s lynching. I examined the responses of activists, artists, writers, and local residents to this appalling act. Turner’s story has had a long, complex afterlife: a tangled mixture of shock, outrage, grief, shame, and, too often, silence. The ways we remember, forget, and erase the history of this lynching is an inescapable part of its story: Even the monument to Mary Turner’s death contains bullet holes from a Winchester .270, normally used for killing deer.

The horror of Turner’s lynching did not stay secret. During the late 1910s and early 1920s, the incident galvanized anti-lynching protest around the country. Writers and artists including Angelina Weld Grimké, Meta Warrick Fuller, Anne Spencer, and Jean Toomer saw the lynching as an example of how racial violence traumatizes individuals, families, and communities. Organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Commission on Interracial Cooperation (CIC) used Turner’s death in magazine exposés and informational pamphlets as evidence that lynching was less about punishment for black male criminality and more about the public performance of white supremacy.

The Anti-Lynching Crusaders, arguing that lynching was an attack on women as well as men, featured Turner as the centerpiece of a campaign to support federal legislation against mob violence. The Crusaders raised money and awareness for the 1922 Dyer Bill, sponsored by Leonidas C. Dyer, a Republican Representative from Missouri, which proposed to make lynching a felony. The bill passed the House but stalled in the Senate when Southern Democrats threatened a filibuster. Although Turner’s lynching was barbaric, more conventional excuses for mob violence—what Ida B. Wells called the “rape myth”—remained intractable.

In time Turner’s name became a historical footnote, as stories like those of the Scottsboro Boys, in 1931, and Emmett Till, in 1955, dominated headlines.

It was not until the late 20th century that writers and artists began to recover Turner as an example of how mainstream history marginalizes black women. The title of Freida High Tesfagiorgis’s 1985 painting about Turner, “Hidden Memories,” captures the sense of erasure that many others find in her story.

Since then, author Honorée Fanonne Jeffers has published short fiction and poetry about Turner, most notably the poem “dirty south moon” in her 2007 volume Red Clay Suite. Playwright Lekethia Dalcoe’s depiction of the incident, A Small Oak Tree Runs Red, was produced in Chicago (2016) and New York (2018). This February, artist Rachel Marie-Crane Williams brought original images from her graphic narrative in progress, Mary Turner and the Lynching Rampage, to Valdosta State University (VSU)—about 20 miles from where Turner died—for a monthlong display.

The historical marker is by the side of State Road 122 in Lowndes County, Georgia. Photo courtesy of Julie Buckner Armstrong.

For some locals, however, Turner’s story remains taboo—and an open wound. The “Lynching Rampage of 1918” occurred during a single week in mid-May and was spread out over two Georgia counties—Brooks and Lowndes. 11 victims were confirmed. Other bodies of African-American males were found but not identified, and others disappeared, never to be heard from again.

Walter White, who investigated the lynchings for the NAACP, publicly named 16 local mob ringleaders, but in fact a large swath of the population likely saw or took part in the events. Hundreds—from Brooks, Lowndes, and surrounding counties—witnessed Mary Turner’s murder, as well as those of Will Head and Will Thompson, two men accused of complicity in the death of the white farmer Hampton Smith. Hayes Turner’s body hung on a main road, just outside the town of Quitman, for a day before it was cut down. When Sidney Johnson, who killed Smith during a wage dispute, was finally captured and shot, the mob dragged his body the 20-plus miles from Valdosta to the small town of Barney, near the site of the present-day historical marker. How many people watched this terrible parade is unclear.

There is no question that the week’s violence affected victims, families, perpetrators, witnesses—and their descendants. Yet when I began researching Mary Turner and the Memory of Lynching in 1998, records were almost impossible to locate. People rarely, if ever, spoke publicly about what happened. Keepers of official civic memory claimed a history of positive race relations, even though Georgia had the second-highest rate of lynchings nationally (following Mississippi). Brooks and Lowndes Counties, because of the 1918 incident, had some of state’s highest numbers.

In the early 2000s, the Mary Turner Project, a small but dedicated group based out of Valdosta State, spearheaded a coalition to erect the historical marker, hoping to end the silence. The marker went up in 2010. Within a year, someone shot a bullet right through its middle.

The approaching 100th anniversary of “Lynching Rampage of 1918” prompts me to consider what I have learned since writing about Mary Turner.

And so much of my knowledge rides on that bullet.

My son found the casing. He was 10 at the time, an eagle-eyed hunter of lizards and bugs. We drove up from our Florida home via I-75, took Exit 29 to Highway 122 heading west, and pulled onto the gravel embankment of the Little River. The book had just come out, and I wanted to make peace with an emotionally difficult project that I had carried around for more than a decade.

I already had heard about the bullet hole. A graduate student passing through for a conference had put a flower in it and snapped a picture, to show me. When the marker went up, the area was nicely landscaped with perennials and mulch. By the time I visited, the flowers were dead. I poked my finger through the bullet hole; my son wandered around in the weeds that were taking over. “Hey Mom,” he said, holding up the casing. “Is this what you’re looking for?

Since then, the marker has been shot at least three more times.

The marker’s text was the result of negotiation between the local Mary Turner Project and the Georgia State Historical Society. Photo courtesy of Julie Buckner Armstrong.

Other historical markers for racial violence have met similar fates. In Florida, the marker depicting the 1923 Rosewood massacre has been repaired multiple times. On my last visit several years ago, chunks were blown out of its protective concrete frame. In 2017, two different Mississippi markers for the 1955 Emmett Till murder were defaced—one by bullets, another by a blunt object. The marker for the 1964 murders of Mississippi Freedom Summer workers James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner was vandalized multiple times and eventually stolen.

Some people actively try to destroy the past. Some erase more passively, waiting for amnesia’s weeds to take over.

Others refuse to let memory die. For the scholars, filmmakers, artists, and writers who continue producing work about Mary Turner, she symbolizes a double injustice. On one level is her brutal death. On another is the way that she ebbs and flows from historical memory.

One might see artist and activist response to Turner as a forerunner of the recent Say Her Name campaign, which attempts to make sure that women are included in public discussions of violence. Decades before the social media hashtag #SayHerName, Mary Talbert’s band of Anti-Lynching Crusaders circulated pamphlets featuring Turner’s story, trying to move women from the margins to the center of a male-dominated narrative.

Turner’s lynching, although gruesome and shocking, was hardly an isolated incident. While statistics vary, a recent attempt by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) to quantify racial violence in the American South documented 4,075 lynchings between 1877 and 1950. The EJI’s report does not separate victims by gender, but University of North Carolina Wilmington criminologist David Victor Baker has confirmed there were 179 female victims. At least three pregnant women other than Turner were lynched. These numbers may be small, but they are significant.

The temptation, when reading stories such as Turner’s, is to think, “down there, back then, not me.” But that impulse is really the desire to silence: the need to place protective distance between our ideal selves and the reality that anyone can be witness, victim, or perpetrator.

Attacking pregnant women has a long and telling history. The Oxford Handbook of Genocide Studies documents multiple occurrences—from the Holocaust to more recent incidents in Bosnia, Rwanda, and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC)—of perpetrators singling out pregnant women for torture, mutilation, and removal of fetuses. The practice goes back to Biblical times. The book of Amos mentions God punishing Ammonites for cutting open pregnant women in Gilead during a border war. An Assyrian poem from c. 1100 B.C. glorifies a military battle where the victor “slits the wombs of pregnant women.”

Looking at Mary Turner within this long, international context reminds us that such violence can take place anytime, anywhere. The sudden ease with which a community can become a mob, or a society can degrade into political violence, is a frightening but sad fact of our shared humanity.

Shooting a hole in a marker does not change the history of Brooks and Lowndes Counties, or the long history of humanity either. Only by confronting—as individuals, communities, and societies—the truth of how we came to be the way we are today, can we make the world better for ourselves and for our children.

My son agrees. As our family drove away from the “Lynching Rampage of 1918,” he told me he hoped the shooter would one day feel remorse and try to make amends.

He said, “You don’t have to like the marker, but you should respect it.”

Send A Letter To the Editors