Culbert Olson being sworn in as governor, with his left hand in his pocket, rather than on the Bible. Photo courtesy of Deborah Olsen.

Culbert Olson is one the most important men you probably never have heard of. He was the only Democrat to serve as governor of California between 1896 and 1958, and he lasted just one term—elected in 1938, and ousted in 1942. He was that rarest of birds among American politicians elected to high office, an atheist and free thinker.

Culbert Olson is one the most important men you probably never have heard of. He was the only Democrat to serve as governor of California between 1896 and 1958, and he lasted just one term—elected in 1938, and ousted in 1942. He was that rarest of birds among American politicians elected to high office, an atheist and free thinker.

He may be best known for refusing to say the words “so help me God,” substituting it with “I will affirm” as he took the governor’s oath of office.

But he was much more than that. He was a progressive who was far ahead of his time, perhaps too far for his own good. I believe now would be a very good time for a reappraisal and deeper understanding of Governor Olson. I say that not merely because Culbert was my grandfather. He proved prescient about the threats to American society—from economic inequality, war, racism, and the dangers of religious tribalism—that are all too much with us today.

“No deity will save us,” he liked to say. “We must save ourselves.”

Olson was born and raised in Utah in the Mormon faith but left the church as a young man after deciding that Joseph Smith was an imposter and that his revelations didn’t make any rational sense. He came to atheism after listening to lectures of one of the most famous American atheists, Robert Green Ingersoll.

He would argue that the Founding Fathers were not Christian, they were deists, and they formed the most secular nation in the world with a strong separation of church and state. Olson, before and during his political career, would urge people to become “humanitarians,” which meant avoiding the bigotry and tribalism associated with organized religions. One of his most quoted statements was, “We should be concerned with the brotherhood of man not the fatherhood of God.”

Olson won a seat in the State Senate in 1934. In that era, Democrats had little chance at winning statewide office. But when Olson was nominated by his party for governor in 1938, he had the good fortune to oppose a highly unpopular and corrupt incumbent, Frank Merriam, at a moment when the Depression was taking another turn for the worse. In November 1938 Olson was featured on the cover of Life magazine, which described him as a handsome, impeccably dressed idol of western politics, looking like a movie star’s projection of a governor. The article informed its readers that “Culbert Levy Olson advances the progressive agenda in California and is known as ‘the people’s governor.’”

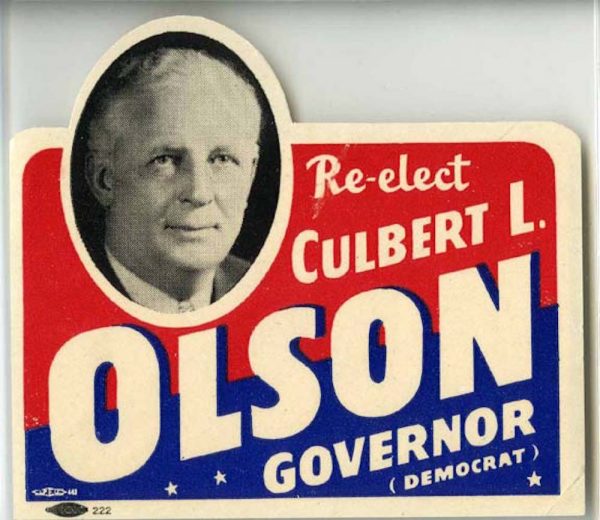

Poster for re-election of Culbert L. Olson as Governor of California, 1942. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

No governor has faced so many obstacles in pursuing his ideas. The California legislature and political establishment dominated by Republicans, and William Randolph Hearst’s right-wing newspapers, opposed almost all of his progressive initiatives and the laws he proposed.

Olson didn’t trust large corporations, especially financially powerful interests. He wanted to support the mainstream American middle class with his progressive ideas. But the legislature defeated most of his programs, which included support for solving the devastating unemployment crisis with the “production for use” concept championed by Upton Sinclair; public ownership of public utilities; universal health insurance for every Californian; legislation to raise taxes on upper-income banks and corporations; and new regulations on lobbyists.

He was successful in breaking up big oil, regulating “loan sharks,” and rewriting usury laws, reforming the largest and most oppressive penal system in the United States at the time, and writing laws to support labor unions.

He didn’t get everything he wanted for his New Deal in California and he made many enemies in the pursuit of his progressive agenda, especially Standard Oil and the Roman Catholic Church (with whom he tangled over its outsized influence in public education). He sought to handle his defeats with humor. He said, “If you want to know where hell is, just be the governor of California.”

Olson’s criticism of corrupt interests was not welcome in Sacramento. He was unapologetically progressive in demanding judicious government regulation of big industry. In 1939, he said: “To my way of thinking, it is the social responsibility of government in promoting the general welfare to exercise control and stabilization of the national economy, to plan and provide for full employment when private industry fails; to prevent business cycles which result in industrial depressions; to provide the ways and means of making available to all the people health protection, and the utmost in educational services; to protect the national resources against wasteful exploitation for private greed.”

During World War II, Olson opposed the incarceration of people of Japanese heritage, which had been supported and defended by the state Attorney General, Earl Warren. In public statements and in a letter to his friend and political confidant, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Olson pointed out that Japanese residents and Japanese Americans were citizens and just as American as anyone else here. In a San Francisco speech, he warned, “Anyone who generates racial hatred and social misunderstanding is a demagogue of the most subversive type. He becomes an enemy of society, just as truly as a tax evader, an embezzler, or a murderer. In fact, he does infinitely more harm.”

Eventually, Governor Olson had to accept the internment after a military order from General John DeWitt, a fervent advocate of incarcerating Japanese Americans. In 1943 he lost his re-election bid to Earl Warren due to the improved economy in California preparing for World War II. In an ironic twist, Warren proved more effective than Olson had been at pushing through some progressive aspects of Olson’s program, including corporate regulation, political reform, and investment in public infrastructure.

After he left office, my grandfather became President of the United Secularists of America, a body of secularists, atheists, and freethinkers. This work included defending separation of church and state, eliminating superstition, promoting taxation of church property, and opposing religion in public schools.

I still hear Grandfather’s humanitarian views in the conversation about income inequality, which is as bad now as it was when he served as governor during the Great Depression. About inequality, he warned: “Social problems are created by economic maladjustments, poverty in the midst of plenty … continued concentration of wealth, control of the national economy in the hands of a small percentage of the population opposing every effort of the government to interpose controls for the economic stabilization and for the general welfare.”

Governor Culbert Olson represented an American tradition of politics that originates from basic human needs and not from personal or financial privilege. His message deserves more thought and attention today.

Send A Letter To the Editors