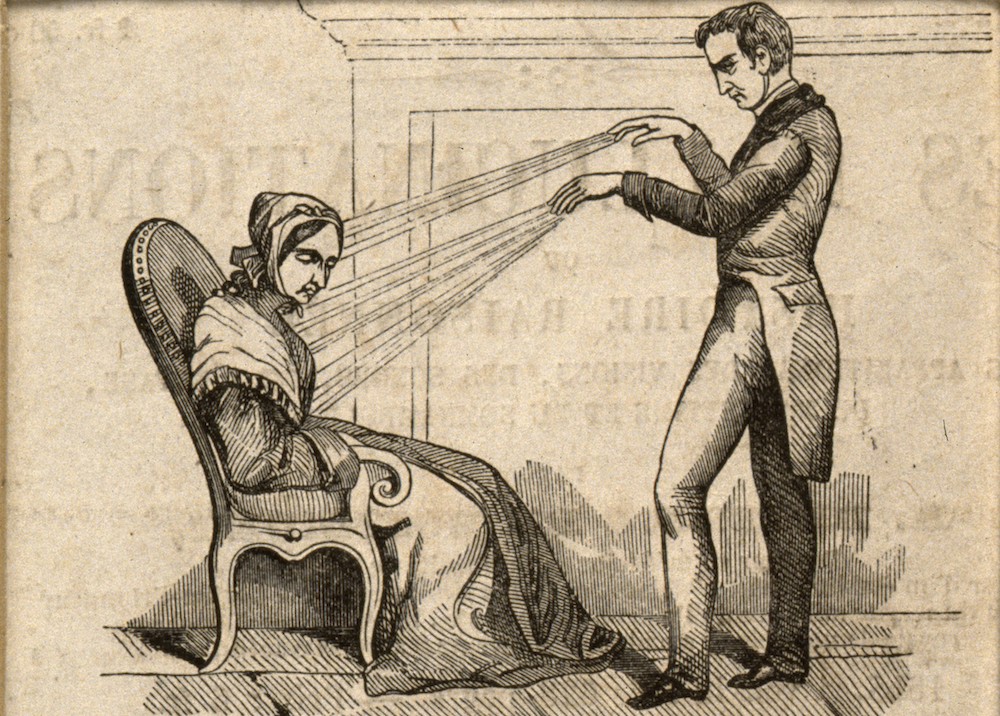

A practitioner of mesmerism using animal magnetism on a woman who responds with convulsions. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

In 1836, a trendy European phenomenon took New England by storm. Charles Poyen, a Frenchman and self-proclaimed professor of animal magnetism, launched a multi-city tour of “mesmeric” theatrical shows, the forerunners of modern hypnotism. Poyen’s mesmeric demonstrations included a professional assistant who diagnosed diseases in audience members, as well as volunteers from the audience who—while entranced—might exhibit insensitivity to sharp objects, locate lost items, or read the minds of people present. Upon waking, the subjects had no recollection of what had happened during their time in a trance.

Poyen also taught people to utilize their own latent powers, spawning a host of “trained” mesmerists in American cities. According to historian Robert C. Fuller, by the early 1840s, between 20 and 30 mesmerists were lecturing in New England. One newspaper account claimed that more than 200 “magnetizers” had set up shop in Boston alone.

Despite its evident entertainment value—and its entrepreneurial nature—mesmerism had roots in 18th-century science. In time, some aspects of mesmerism would be forgotten, while others would lead to work on spiritual enlightenment and even the science of psychology itself. During its heyday, mesmerism straddled lines between popular culture and scientific discovery, religion and science, lowbrow and highbrow culture.

While recorded occurrences of the trance state date back millennia, the term and official practice of mesmerism emerged from the work of Franz Anton Mesmer, an Austrian physician and astrologer. In his writings from the 1770s and 1780s, Mesmer describes an invisible and universal “fluid,” or energy, that exists in all people and helps sustain good health when kept in equilibrium. He likened this invisible force to magnetism and even used magnets to align the forces within individuals with the forces of nature.

The use of magnets evolved into the practice of a healthy person passing his hands over a sick individual to redistribute “magnetic fluid” and pull out any disease. As Mesmer’s practices gained popularity in Europe, “mesmerism” became synonymous with the radical healing practices attributed to “animal magnetism.” Mesmer claimed a rational method behind his work and developed his theory of universal fluid from Isaac Newton’s electromagnetic aether and laws of attraction, lending his work scientific credibility, however tenuous. Research successfully inducing and harnessing electricity, another invisible force, only served to substantiate mesmerists’ claims.

Briefly fashionable in Vienna, mesmerism declined in popularity after several scandals and unsuccessful attempts at healing. When Mesmer moved to Paris in 1778, events followed a similar trajectory. Mesmer attracted many followers, which led King Louis XVI to appoint a commission from the Faculty of Medicine and the Royal Academy of Sciences to investigate the phenomenon of animal magnetism. American ambassador Benjamin Franklin served on this commission. The commission’s unfavorable report found no evidence of magnetic fluid. The effects of mesmerism, they pronounced, might be attributed to the imagination.

Mesmer’s influence, however, could not be squelched. Practitioners of magnetism found that some patients had a tendency to become entranced during their treatment, especially when the physician focused his passes on the patient’s head. Mesmer and his pupils referred to this state, in which a person is alert and communicative but does not seem to be awake, as somnambulism (derived from the French somnambulisme, or sleepwalking). In these trance-like states, somnambulists displayed a heightened, perceptive intelligence. More importantly for physicians who supported mesmerism, somnambulists often displayed a gift for diagnosing both their own illnesses and the illnesses of others, from heart disease to menstrual aches to melancholia.

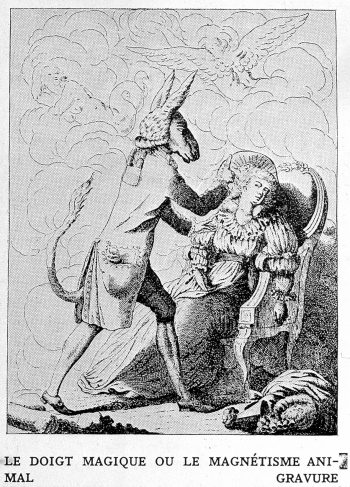

The doctor, having discarded his wig and cloak hypnotises the woman in the guise of Bottom from ‘Midsummer Might’s Dream’. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Thus, animal magnetism gained a degree of credibility as a medical science by revealing a fascinating pathway to what we now call the unconscious mind. It was this evolution in mesmerism that would propel it into the 19th century and American culture, paving the way for mental healing movements and the eventual rise of psychology as an academic discipline.

In keeping with the American spirit of democracy, mesmeric powers were not restricted to the learned or well-to-do; to practice this healing art, no formal education was required. One of America’s most prolific trance lecturers, and later Spiritualists, was Andrew Jackson Davis, a young apprentice with little formal education. And, while women were most often the subjects of mesmeric demonstrations, some women found that the trance state granted them voice and authority in the public sphere, as Anne Braude has shown.

Coming on the heels of the Age of Reason, mesmerism intrigued many intellectuals. Edgar Allan Poe was in Davis’ audience one evening in 1845. He features the mesmeric trance as a form of escape in three short stories published in the mid-1840s: “A Tale of the Ragged Mountains,” “Mesmeric Revelation,” and “The Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar.” Poe’s penchant for hoaxes and the fantastic should make us skeptical of whether he was promoting or exploiting mesmerism in these stories. Regardless, Poe may be counted among a number of mid-century intellectuals who investigated the mesmeric trance.

Margaret Fuller, a notable female transcendentalist, writer, and editor, visited a mesmerist on multiple occasions for relief from debilitating headaches and an aching spine. Her close friend, prominent Unitarian minister James F. Clarke, hosted a mesmeric club at his home during the winter and spring of 1844, with attendees including Fuller and Joseph Rodes Buchanan. Buchanan, a physician and professor of physiology, and Unitarian ministers Ephraim Peabody and Chandler Robbins, joined Clarke in his mesmeric investigations, experimenting with consciousness and approaching spirituality in novel ways.

Mesmerism occupied a gray area between religion and science before firm lines were drawn between the two. In the mesmeric trance, it was thought, people might rid themselves of material encumbrances, gaining pure insight to the spiritual realm. Religious intellectuals hoped this meeting of science and spiritual awareness might usher in a new era of Christianity, one of palpable access to the spirit or even a way to reconcile body and spirit.

Unsurprisingly, this trendy new practice also had detractors. Mesmerism commonly involved a male mesmerist waving his hands around the head, and often the body, of a woman. There was an erotic element to mesmeric practice that wasn’t lost on all spectators and drew the ire of some of the era’s intellectual leaders.

In an 1839 lecture titled “Demonology,” Ralph Waldo Emerson described animal magnetism as “high life below the stairs.” He pondered that, “the peculiarity of the history of Animal Magnetism is that it drew in as inquirers and students a class of persons never on any other occasion known as students and inquirers.” Emerson’s comments illustrate concern about the lower classes gaining cultural authority through claims of mesmeric power and the credulity of American audiences. He further declared that “the inquiry is pursued on low principles” and “becomes in such hands a black art.”

In a pamphlet published in 1845, “Confessions of a Magnetiser,” one former mesmerist admitted to sexually assaulting women who were his mesmeric subjects, claiming that the submission of beautiful young women who were his “patients” was simply more than he could bear.

Nathaniel Hawthorne strongly urged his fiancée, Sophia Peabody, to avoid mesmeric treatments for her ailments, describing mesmerism as “an intrusion into thy holy of holies.” He depicts mesmerists as self-serving manipulators in his novels The House of the Seven Gables (1851) and The Blithedale Romance (1852).

Another devious depiction of animal magnetism comes in the Quarterdeck scene of Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick (1851), when Captain Ahab grasps crossed harpoons and transmits the volition of “his own magnetic life” to his three mates, inducing them to join his quest for vengeance on the white whale. For these cultural luminaries, mesmerism held substantial grounds for suspicion and distrust.

By the 1850s mesmerism’s popularity had waned. In Scotland, surgeon James Braid stripped mesmerism of all references to human magnetism and rebranded it as hypnotism, the terminology that lingers into the 21st century.

Still, the peculiarities of the trance state were a challenge for contemporary and future scientists to address. Charles Darwin considered and dismissed the practice of mesmerism as he formulated his theory of the evolution of consciousness. In one of his notebooks, Darwin wrote of double consciousness (as evidenced in the trance state) as a phenomenon that “must be considered profoundly.”

In the late 1880s, Sigmund Freud, who had attended demonstrations of hypnotism, integrated it into his own clinical practice for a brief time, conceiving of hypnosis as a spring that released unconscious thoughts. Hypnosis contributed to Freud’s theory of the unconscious mind as a storing ground for repressed ideas or memories.

And so the brief 19th-century love affair with mesmerism left its mark on both science and culture. Its key features—an alternate level of consciousness and a method for systematically accessing it—were tributaries that flowed into the paradigm-shifting intellectual currents of the following century. Science and the general public, too, would sail into modernity continuing to experiment with a portion of the self that resided just below waking consciousness.

Send A Letter To the Editors