Camping for fun has been around since at least 1869, writes Terence Young. As more people could afford vehicles and vacations, inventions like the RV allowed a mix of “roughing it” and modern comforts. Courtesy of David~O/Flickr.

Zócalo’s editors are diving into our archives and throwing it back to some of our favorite pieces. This week: Before pandemic “van life,” there were the “Gypsy Van” and the “Pullman Coach.” Geographer Terence Young explores the history of American recreational vehicles.

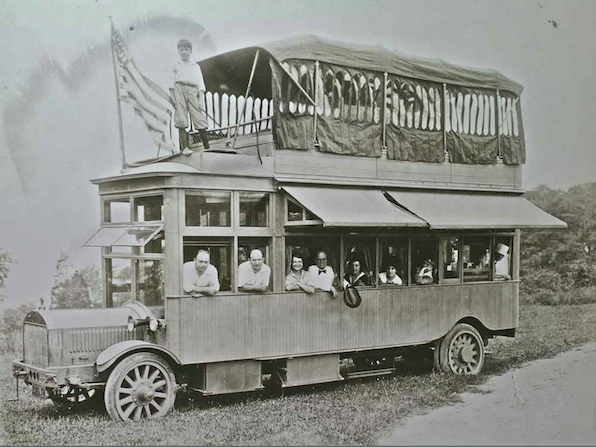

On August 21, 1915, the Conklin family departed Huntington, New York on a cross-country camping trip in a vehicle called the “Gypsy Van.” Visually arresting and cleverly designed, the 25-foot, 8-ton conveyance had been custom-built by Roland Conklin’s Gas-Electric Motor Bus Company to provide a maximum of comfort while roughing it on the road to San Francisco. The New York Times gushed that had the “Commander of the Faithful” ordered the “Jinns… to produce out of thin air… a vehicle which should have the power of motion and yet be a dwelling place fit for a Caliph, the result would have fallen far short of the actual house upon wheels which [just] left New York.”

On August 21, 1915, the Conklin family departed Huntington, New York on a cross-country camping trip in a vehicle called the “Gypsy Van.” Visually arresting and cleverly designed, the 25-foot, 8-ton conveyance had been custom-built by Roland Conklin’s Gas-Electric Motor Bus Company to provide a maximum of comfort while roughing it on the road to San Francisco. The New York Times gushed that had the “Commander of the Faithful” ordered the “Jinns… to produce out of thin air… a vehicle which should have the power of motion and yet be a dwelling place fit for a Caliph, the result would have fallen far short of the actual house upon wheels which [just] left New York.”

For the next two months, the Conklins and the Gypsy Van were observed and admired by thousands along their westward route, ultimately becoming the subjects of nationwide coverage in the media of the day. Luxuriously equipped with an electrical generator and incandescent lighting, a full kitchen, Pullman-style sleeping berths, a folding table and desk, a concealed bookcase, a phonograph, convertible sofas with throw pillows, a variety of small appliances, and even a “roof garden,” this transport was a marvel of technology and chutzpah.

For many Americans, the Conklin’s Gypsy Van was their introduction to Recreational Vehicles, or simply, RVs. Ubiquitous today, our streamlined motorhomes and camping trailers alike can trace their origins to the time between 1915 and 1930, when Americans’ urge to relax by roughing it and their desire for a host of modern comforts first aligned with a motor camping industry that had the capacity to deliver both.

The Conklins did not become famous simply because they were camping their way to California. Camping for fun was not novel in 1915: It had been around since 1869, when William H.H. Murray published his wildly successful Adventures in the Wilderness; Or, Camp-Life in the Adirondacks, America’s first “how-to” camp guidebook.

Ever since Murray, camping literature has emphasized the idea that one can find relief from the noise, smoke, crowds, and regulations that make urban life tiresome and alienating by making a pilgrimage to nature. All one needed to do was head out of town, camp in a natural place for a while, and then return home restored in spirit, health and sense of belonging. While in the wild, a camper—like any other pilgrim—had to undergo challenges not found at home, which is why camping has long been called “roughing it.” Challenges were necessary because, since Murray’s day, camping has been a recapitulation of the “pioneer” experience on the pre-modern “frontier” where the individual and family were central and the American nation was born.

Camping’s popularity grew slowly, but got more sophisticated when John B. Bachelder offered alternatives to Murray’s vision of traveling around the Adirondacks by canoe in his 1875 book Popular Resorts and How to Reach Them. Bachelder identified three modes of camping: on foot (what we call “backpacking”); on horseback, which allowed for more gear and supplies; and with a horse and wagon. This last was most convenient, allowing for the inclusion ‘of more gear and supplies as well as campers who were unprepared for the rigors of the other two modes. However, horse-and-wagon camping was also the most costly and geographically limited because of the era’s poor roads. In short order, Americans across the country embraced all three manners of camping, but their total number remained relatively small because only the upper middle classes had several weeks’ vacation time and the money to afford a horse and wagon.

Over the next 30 years, camping slowly modernized. In a paradoxical twist, this anti-modern, back-to-nature activity has long been technologically sophisticated. As far back as the 1870s, when a new piece of camping gear appeared, it was often produced with recently developed materials or manufacturing techniques to improve comfort and convenience. Camping enthusiasts, promoters, and manufacturers tended to emphasize the positive consequences of roughing it, but, they added, one didn’t have to suffer through every discomfort to have an authentic and satisfying experience. Instead, a camper could “smooth” some particularly distressing roughness by using a piece of gear that provided enhanced reliability, reduced bulk, and dependable outcomes.

Around 1910 the pace of camping’s modernization increased when inexpensive automobiles began appearing. With incomes rising, car sales exploded. At the same time, vacations became more widespread—soon Bachelder’s horses became motor vehicles, and all the middle classes started to embrace camping. The first RV was hand built onto an automobile in 1904. This proto-motorhome slept four adults on bunks, was lit by incandescent lights and included an icebox and a radio. Over the course of the next decade, well-off tinkerers continued to adapt a variety of automobiles and truck chassis to create even more spacious and comfortable vehicles, but a bridge was crossed in 1915 when Roland and Mary Conklin launched their Gypsy Van.

Unlike their predecessors, the wealthy Conklins modified a bus into a fully furnished, double-deck motorhome. The New York Times, which published several articles about the Conklins, was not sure what to make of their vehicle, suggesting that it was a “sublimated English caravan, land-yacht, or what you will,” but they were certain that it had “all the conveniences of a country house, plus the advantages of unrestricted mobility and independence of schedule.” The family’s journey was so widely publicized that their invention became the general template for generations of motorhomes.

When the Conklin family traveled from New York to San Francisco in their luxury van, the press covered their travels avidly. Courtesy of the George Grantham Bain Collection at the Library of Congress.

The appeal of motorhomes like the Conklins’ was simple and clear for any camper who sought to smooth some roughness. A car camper had to erect a tent, prepare bedding, unpack clothes, and establish a kitchen and dining area, which could take hours. The motorhome camper could avoid much of this effort. According to one 1920s observer, a motorhome enthusiast simply “let down the back steps and the thing was done.” Departure was just as simple.

By the middle of the 1920s, many Americans of somewhat more average means were tinkering together motorhomes, many along the lines made popular by the Conklins, and with the economy booming, several automobile and truck manufacturers also offered a limited number of fully complete motorhomes, including REO’s “speed wagon bungalow” and Hudson-Essex’s “Pullman Coach.”

In spite of their comforts, motorhomes had two distinct limitations, which ultimately led to the creation of the RV’s understudy: the trailer. A camper could not disconnect the house portion and drive the automobile part alone. (The Conklins had carried a motorcycle.) In addition, many motorhomes were large and limited to traveling only on automobile-friendly roads, making wilder landscapes unreachable. As a consequence of these limitations and their relatively high cost, motorhomes remained a marginal choice among RV campers until the 1960s. Trailers, by contrast, became the choice of people of average means.

The earliest auto camping trailers appeared during the early 1910s but they were spartan affairs: a plain device for carrying tents, sleeping bags, coolers, and other camping equipment. Soon, motivated tinkerers began to attach tent canvas on a collapsible frame, adding cots for sleeping and cupboards for cooking equipment and creating the first “tent trailers.” By mid-decade, it was possible to purchase a fully equipped, manufactured one. In 1923’s Motor Camping, J.C. Long and John D. Long declared that urban Americans were “possessed of the desire to be somewhere else” and the solution was evident—trailer camping. Tent trailering also charmed campers because of its convenience and ease. “Your camping trip will be made doubly enjoyable by using a BRINTNALL CONVERTIBLE CAMPING TRAILER,” blared an advertisement by the Los Angeles Trailer Company. The trailer was “light,” incorporated “comfortable exclusive folding bed features,” and had a “roomy” storage compartment for luggage, which left the car free to be “used for passengers.”

Tent trailering, however, had some drawbacks that became clear to Arthur G. Sherman in 1928 when he and his family headed north from their Detroit home on a modest camping trip. A bacteriologist and the president of a pharmaceutical company, Sherman departed with a newly purchased tent trailer that the manufacturer claimed could be opened into a waterproof cabin in five minutes. Unfortunately, as he and his family went to set it up for the first time, a thunderstorm erupted, and claimed Sherman, they “couldn’t master it after an hour’s wrestling.” Everyone got soaked. The experience so disgusted Sherman that he decided to create something better.

The initial design for Sherman’s new camping trailer was a masonite body standing six-feet wide by nine-feet long and no taller than the family’s car. On each side was a small window for ventilation and two more up front. Inside, Sherman placed cupboards, icebox, stove, built-in furniture and storage on either side of a narrow central aisle. By today’s standards, the trailer was small, boxy and unattractive, but it was solid and waterproof, and required no folding. Sherman had a carpenter build it for him for about $500 and the family took their new “Covered Wagon” (named by the children) camping the following summer of 1929. It had some problems—principally, it was too low inside—but the trailer aroused interest among many campers, some of whom offered to buy it from him. Sherman sensed an opportunity.

That fall, Sherman built two additional Covered Wagons. One was for a friend, but the other one he displayed at the Detroit Auto Show in January 1930. He set the price at $400, which was expensive, and although few people came by the display, Sherman reported that they were “fanatically interested.” By the end of the show, he had sold 118 units, the Covered Wagon Company was born, and the shape of an RV industry was set.

Over the next decade the company grew rapidly and to meet demand, trailers were built on an assembly line modeled on the auto industry. In 1936, Covered Wagon was the largest trailer producer in an expanding American industry, selling approximately 6,000 units, with gross sales of $3 million. By the end of the 1930s, the solid-body industry was producing more than 20,000 units per year and tent trailers had more or less disappeared.

Arthur Sherman’s solid-body trailer quickly gained acceptance for two principal reasons. First, Sherman was in the right place, at the right time, with the right idea. Detroit was at the center of the Great Lakes states, which at that time contained the country’s greatest concentration of campers. Furthermore, southern Michigan was the hub of the automobile industry, so a wide range of parts and skills were available, especially once the Depression dampened demand for new automobiles. And, a solid-body trailer took another step along the path of modernization by providing a more convenient space that was usable at any time.

Today’s 34-foot Class A motorhome with multiple TVs, two bathrooms, and a king bed is a version of the Conklin’s “Gypsy Van” and fifth-wheel toy haulers with popouts are the descendants of Arthur Sherman’s “Covered Wagon,” and these, in turn, are modernized versions of Bachelder’s horse-and-wagon camping. Between 1915 and 1930, Americans’ desire to escape modern life’s pressures by traveling into nature intersected with their yearning to enjoy the comforts of modern life while there. This contradiction might have produced only frustration, but tinkering, creativity, and a love of autos instead gave us recreational vehicles.

Send A Letter To the Editors