The Fisk Jubilee Singers in early 1872. Seated (L to R): Minnie Tate, Greene Evans, Jennie Jackson, Ella Sheppard, Benjamin Homes, Eliza Walker. Standing: Isaac Dickerson, Maggie Porter, Thomas Rutling. Courtesy of Sandra Jean Graham.

“Swing low, sweet chariot….” These words are familiar to many Americans, who might sing them in worship, in Sunday school, around campfires, in school, and in community choruses. But the black singers responsible for introducing this song, and hundreds of other slave spirituals, to white America after the Civil War remain underrecognized almost 150 years later.

“Swing low, sweet chariot….” These words are familiar to many Americans, who might sing them in worship, in Sunday school, around campfires, in school, and in community choruses. But the black singers responsible for introducing this song, and hundreds of other slave spirituals, to white America after the Civil War remain underrecognized almost 150 years later.

Spirituals are sacred songs composed anonymously by black Americans. Before the Civil War they were sung in the privacy of black spaces—the brush arbor, the praise house, the cotton field, the levee. After the Civil War, however, groups of student singers representing black educational institutions brought spirituals to the concert stage. The impact of hearing spirituals from the lips of people who were formerly enslaved was profound, particularly among white Northerners who had been abolitionists. Their enthusiastic championing of these songs gave rise to a new musical genre, as an entertainment industry based on spirituals was sung into existence.

Spirituals began their transition to the concert hall in 1871 in an effort to save Fisk University from financial ruin. The school had been founded by the American Missionary Association in 1866 in Nashville for the education of freedmen. Its white treasurer, George White, was an amateur musician who in his spare time trained a group of some 10 to 12 female and male singers. Their repertory consisted of white parlor songs and hymns of the day until White overheard the students singing spirituals to one another. He then prevailed on them to teach him the songs.

After a series of local concerts, White gambled with the school’s and his personal savings by taking his singers on tour. In October 1871 they set out for the north, initially touring towns and cities on the Underground Railroad from Ohio to Maine. Audiences met the parlor songs with indifference but enthusiastically embraced the spirituals.

White arranged the spirituals with the goal of transforming a participatory folk music into a concert music that would hold the attention of a listening audience. This meant training his singers to blend and synchronize their voices. He typically added harmony, regulated the rhythm, added dynamics and other expressive features, and changed dialect to standard English. Church musician Theodore Seward (also white) transcribed the songs, which were sold in books at concerts. Through this process, improvisatory songs became standardized.

In 1874, the Fisk Jubilee Singers went to England, spending most of their career in Britain and on the Continent until they disbanded in 1878. Over the course of their short career they collected $150,000 for their university.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers are justifiably renowned for their artistry, fundraising, and consciousness-raising. But public enthusiasm for jubilee songs might well have died out once the singers began performing abroad, had not numerous other jubilee groups materialized. Although the popularization of jubilee songs—as spirituals became known—began with the Fisk singers, it certainly didn’t end with them.

Fisk’s first serious rivals were the Hampton Institute Singers, who sang under white director Thomas Fenner on behalf of Hampton Institute (later renamed Hampton University) in Hampton, Virginia.

If George White’s arrangements subjected the spirituals to precise pitches and standardized language, Fenner demonstrated a greater appreciation for folk performance and an enthusiasm for preservation. He retained ornaments like vocal slides and melismas in the melodies, created a denser texture by using up to seven separate voice parts (compared with White’s typical soprano-alto-tenor-bass), permitted the flexible approach to pitch typical of folk practice, retained dialect, and featured a “shouter”—a soloist who encouraged exuberance in the singers and listeners. Fenner’s more folkloric approach to spirituals was also evident in the origin stories that often prefaced the transcriptions in the Hampton anthologies of spirituals.

When the Hampton troupe began touring in 1873, they followed similar routes to the Fisk singers, singing in churches and cities where their sponsor, the American Missionary Association, could assist them. They enjoyed great success until the financial panic of 1873 curtailed their first season. After a brief respite they regrouped and struck out for the West and Canada, where the Fisks hadn’t yet sung. Unfortunately, a heat wave and grasshopper plagues kept audiences away, and the group returned east in defeat, rebounding in 1875 for a final, successful, tour.

If the Hampton singers weren’t as financially fortunate as the Fisks, they nonetheless introduced new spirituals to the public, being careful not to duplicate the Fisk repertory, and spread spirituals to new parts of the country. In their more folkloric approach, the Hamptons introduced new concepts of perceived “authenticity” to white concertgoers.

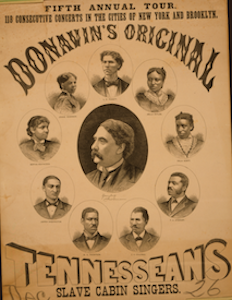

A poster for Donavin’s Tennesseans, circa 1878. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Authenticity became a primary marketing strategy for future jubilee groups. In the minds of the white public, authenticity meant that the singers were former slaves who were bringing spirituals direct from the plantation—even though some of the Fisk Jubilee Singers, and many who followed in their wake, were born free. Whereas the Fisk Jubilee Singers’ formal dress, careful vocal cultivation, and characterization of their concerts as “services of song” emphasized the missionary nature of their work, other groups embraced the connection to slavery. In 1874, a jubilee troupe known as the Tennesseans began advertising “slave cabin concerts.” Launched by white Methodist layman John Wesley Donovan, the Tennesseans initially sang on behalf of Central Tennessee College in Nashville.

Although at first the Tennesseans sang the same spirituals that the Fisks had introduced, over time their repertory grew to be largely distinct, growing to 166 spirituals. Furthermore, at least some of their arrangements were made by their bass singer, Leroy (L.N.D.) Pickett, making them the earliest known examples of concert spiritual arrangements credited to an African American. The Tennesseans eventually became an independent troupe, and Pickett served as their musical director from 1882 before going on to direct the Wilberforce Concert Company in 1886.

Some jubilee troupes, such as the North Carolinians and the Wilmington [N.C.] Jubilee Singers (both established in 1874), distinguished themselves not merely with claims to authenticity but with “demonstrations of slave life” onstage. Reviewers in the North Carolinians’ early years claimed that if the singers couldn’t compare with the Tennesseans in cultivation and training, having been taken “directly from the plantations,” they did offer a “more accurate representation” of slave life. An 1876 program of one of their entertainments begins with a minstrel-style musical sketch called “Old Pompey,” with characters in “actual” slave costumes. Almost the entire program would have found a welcome home in a blackface minstrel show, with the exception of a handful of spirituals at the end of the program. Even so, the intent seemed to be to educate. One part of the show, entitled “The Jaw Bones,” demonstrated a variety of plantation instruments with a “historical view of how they were used.”

The Wilmington Jubilee Singers likewise walked the tightrope between jubilee singing and minstrelsy, and their hybrid entertainments became the model for most commercial jubilee troupes of the later 1870s and 1880s, among them Sheppard’s Jubilee Singers, the Nashville Students, and Slavin’s Georgia Jubilee Singers. Such troupes presented their plantation sketches, costumes, instruments, songs, and dances as ethnographies of slave life, which heightened their identification with slavery in the minds of their northern white audiences.

At the same time that these hybrid minstrel-jubilee troupes proliferated, student groups devoted solely to the performance of spirituals and other concert music continued to form and tour. Historically black colleges such as Wilberforce and Tuskegee formed jubilee troupes, and several ensembles associated with former Jubilee Singers continued to use the Fisk name in the 1880s, most notably one under the direction of original Jubilee Singer Frederick Loudin. Churches and communities formed their own local troupes. By the turn of the century, some 85 jubilee ensembles (and undoubtedly many more that haven’t yet been uncovered) were singing spirituals onstage in all parts of the country, as well as in Europe, South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and India.

This nascent jubilee industry had all of the competitive pressures of the American entertainment marketplace. Managers competed with each other for singers and for audiences. Troupes exploited each other, appropriating arrangements and even endorsements (printed in ads and programs), so that managers felt compelled to protect their brand by proclaiming their originality.

Although the earliest jubilee troupes were sponsored by white missionary societies and black colleges, it wasn’t long before independent ensembles were formed. The white managers who had predominated initially began to be elbowed aside by black entrepreneurs and arrangers. As the jubilee marketplace grew, it splintered, with some groups stressing their cultivation (associating with churches, lyceum bureaus, and Chautauquas) while others exploited white fascination with slave life. Regardless of which route a troupe took—and many troupes took both—“authenticity” and “preservation” became their watchwords.

Had there been no rivals to the pioneering Fisk Jubilee Singers, who knows how long it would have been before the spiritual became an American national music—or whether that would have even happened. Without jubilee singers to incite public fascination with this music, there likely would have been no parodies of spirituals in minstrel and variety shows. Without jubilee singers, the immensely popular postwar stage adaptations of Uncle Tom’s Cabin would have lost a main attraction. Without jubilee singers, music publishers wouldn’t have profited from the hundreds of anthologies and sheet music editions of spirituals they sold. And without jubilee singers, it could have taken much longer for a spiritual like “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” to enter mainline church hymnals.

The Fisk Jubilee Singers deserve every honor they have earned for their pioneering work in popularizing spirituals in American culture. But they could not have spawned an enduring jubilee industry without the jubilee performers who competed, imitated, and innovated in their wake. Without those competitors, the jubilee mania might have sputtered and died. Instead, they helped make spirituals a permanent cultural force and signifier of American musical identity.

Send A Letter To the Editors