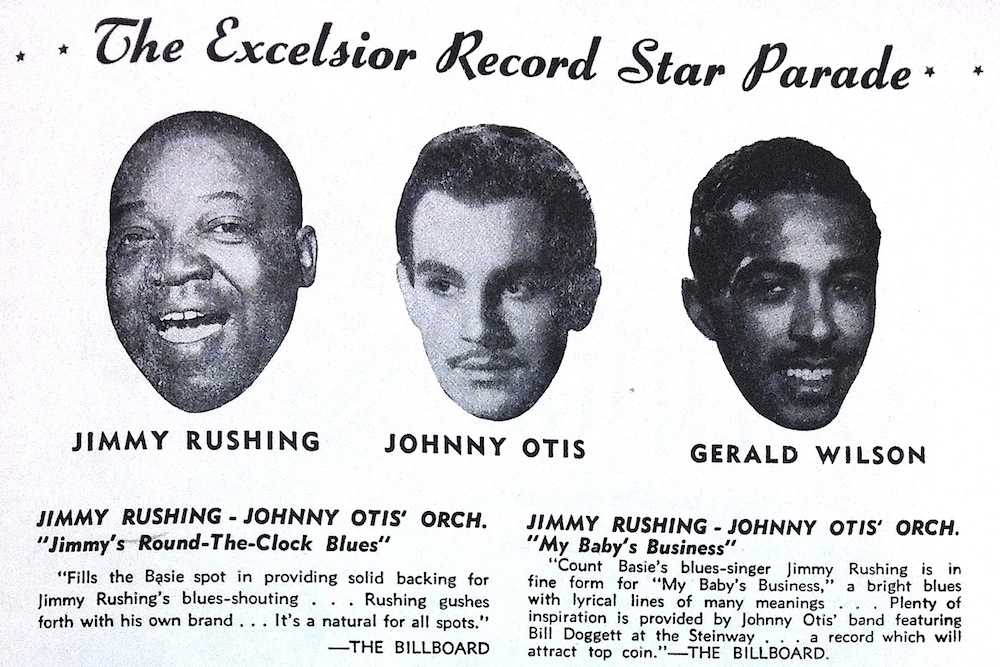

An Excelsior Records advertisement features R&B pioneer Johnny Otis between blues singer Jimmy Rushing and bandleader Gerald Wilson. Courtesy of Flickr.

If a role exists in black music that Johnny Otis couldn’t play, it would be hard to find. Known as the godfather of rhythm and blues, Otis was a bandleader, talent scout, singer, drummer, minister, journalist, and television show host. Between 1950 and 1952, Johnny and his band recorded 15 top 40 R&B blues hits. He discovered, produced and promoted a roster of stars, including Etta James, Little Esther, and Jackie Wilson.

Otis was not only a trailblazer in the world of music but also a religious leader and political activist. Born seven months after the beginning of the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot, he lived through Supreme Court decisions that decriminalized interracial marriage, barred racial gerrymandering of political districts, and ended covenants barring black Americans from owning property. He witnessed the inauguration of the nation’s first African-American president and was a friend of Malcolm X and an enemy of racial oppression. Yet Johnny Otis, arguably one of the most important figures in mid-century black music in America, was not actually black. He was white, passing as black.

In the context of American history, “passing” is generally associated with African-descended blacks clandestinely assuming a white identity to access rights and privileges otherwise denied them. Prior to the passage of the 13th Amendment in 1865, passing meant freedom from a brutal life of chattel slavery. During Jim Crow, it meant access to better housing, schools, banks, jobs, and labor unions.

However, there have been several deviations from the cultural norm in American history that involved appropriating various aspects of black culture, including white-to-black passing. The life, dissemblance, and artistic contribution of Otis—often referred to as the original “King of Rock and Roll”—provides an example of the complexities of this reverse passage, one which was made publicly.

While black popular culture today can be seen as the confluence of multiple cultural traditions, during the early 1900s “blackness” was defined by the one-drop rule, which asserted that any person with even one drop of black blood was considered black. This was a response to English common law, in which children inherited the legal status of their father, but slaveholders took advantage of a rule of descent that would guarantee to owners all offspring of slave women, regardless of who the father was. Under the contortions of racial laws, a person could be very light-skinned and yet considered legally black.

Still, there is no ambiguity with respect to the parentage of Johnny Otis. Three days after Christmas in 1921, Alexander J. Veliotes, a longshoreman and grocery store owner, and his wife Irene, a painter who had immigrated from Greece, welcomed a son into the world. This son, Ionnis Alexandres Veliotes, would later change his name to Johnny Otis.

Between 1880 and 1920, nearly 35 million people, mainly from southern and eastern Europe, arrived in the United States. Rapid economic growth in the United States created a demand for immigrant workers. This created a labor shortage, especially during construction of the railroad linking the East and West Coasts. Though their labor was needed, many Americans were not comfortable with these new Greek neighbors, a significant number of whom were not Protestants and had darker skin than white Americans who had immigrated from northern Europe.

Growing up in an African-American neighborhood in Berkeley, California, Otis spent his early years immersed in black culture and music. Identifying more with African-American culture than his own Greek background led him to adopt a new name, believing that it sounded more black. He recalled at one point being told as a teen by a school counselor that he should be spending more time with white classmates. He pointedly wrote, “[a]s a kid I decided that if our society dictated that one had to be either black or white, I would be black.”

For Otis, identity was more a matter of culture than color. Living as a “black” man enabled Otis to be a part of the world that he understood best and that meant the most to him. Otis explained in his autobiography that he knew that there were some dimensions of the African-American experience that he couldn’t feel; that his parentage allowed him the theoretical option of living as “white.”

Though he was not born into black America, he championed that community as it fought for civil rights. He made appearances at sit-ins targeting segregated lunch counters. He wrote opinion pieces for the Los Angeles Sentinel about issues affecting L.A.’s black community, including a condemnation of California’s segregated housing laws. One night in 1960, he got a threatening phone call at home and looked out the window to see a cross burning on his lawn. His absorption in black culture became such an internalized part of his experience that he found it impossible to think of himself in any other terms. In 1979, Otis told the Los Angeles Times, “Yes, I chose, because despite all the hardships, there’s a wonderful richness in black culture that I prefer.”

Otis displayed his respect for black culture and black people openly because he felt that he had been saved by their political, spiritual, and moral force. When he was 19, Johnny Otis married a childhood friend from Oakland, 18-year-old Phyllis Walker, whose heritage was African-American and Filipino. The couple eloped in Reno, Nevada, over the objections of Otis’s mother. Their union lasted 71 years until Otis’s death of natural causes in Altadena, California on January 17, 2012.

The Watts Riots during the summer of 1965 inspired Otis to write “Listen to the Lambs,” a compelling text exploring the racial oppression and collective turmoil of blacks in America. He was commissioned to write his second book, Upside Your Head!: Rhythm and Blues on Central Avenue, about rhythm and blues music and the Central Avenue culture in early Los Angeles.

Otis was half-finished with the book when the 1992 Los Angeles Riots erupted after a trial acquitted four Los Angeles police officers for use of excessive force in the arrest and beating of Rodney King. In the preface he writes: “I have never thought that extreme hate groups such as the Ku Klux Klan, Nazis, and so on posed the biggest danger to African Americans and other minorities. The real culprits are the average, run-of-the-mill, law-abiding white Americans. Those who go to church, mow their lawns, and deplore racism and injustice. When something as horrendous as the Rodney King beating is thrust in their faces, they are outraged but actually do nothing more than cluck their tongues…they know goddamned well that they are to blame.”

Scholarly inquisition into Otis’s life has also helped fuel heated discourse on appropriating blackness and an understandable suspicion of white-to-black passing. Otis, however, was not a racial impostor; he never denied his family origin.

In 1975, Otis was ordained as a minister. Three years later, he founded the New Landmark Community Gospel Church in Santa Rosa, California. Services were held at the church until it closed in 1998.

Otis also became an important nurturer of the musical traditions that had brought him fame. During the 1980s, he became concerned about the audiences for his television show “The New Johnny Otis Show” and for his music. He feared that the music of such musical greats as Mahalia Jackson, Dinah Washington, and Count Basie would be forgotten by the black community. Inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1994, his contribution to the genre of rhythm and blues includes such classics as “That’s Your Last Boogie,” “Rockin’ Blues,” and “Willie and the Hand Jive.” His work led to opportunity for many young black singers and musicians, but also to a life of money and fame for himself.

Otis was in some important ways different from the musicians who followed him in adopting black music and self-expression. While rap and hip-hop superstars like Vanilla Ice, Eminem, and Iggy Azalea could be seen as appropriating black music styles, none of them actually claimed to be black. But among performers who did try to pass as “black” and those who built a lucrative empire out of black culture, perhaps no one else so fully become a part of the community that spurred them to success or gave as much back to it as Johnny Otis.

Send A Letter To the Editors