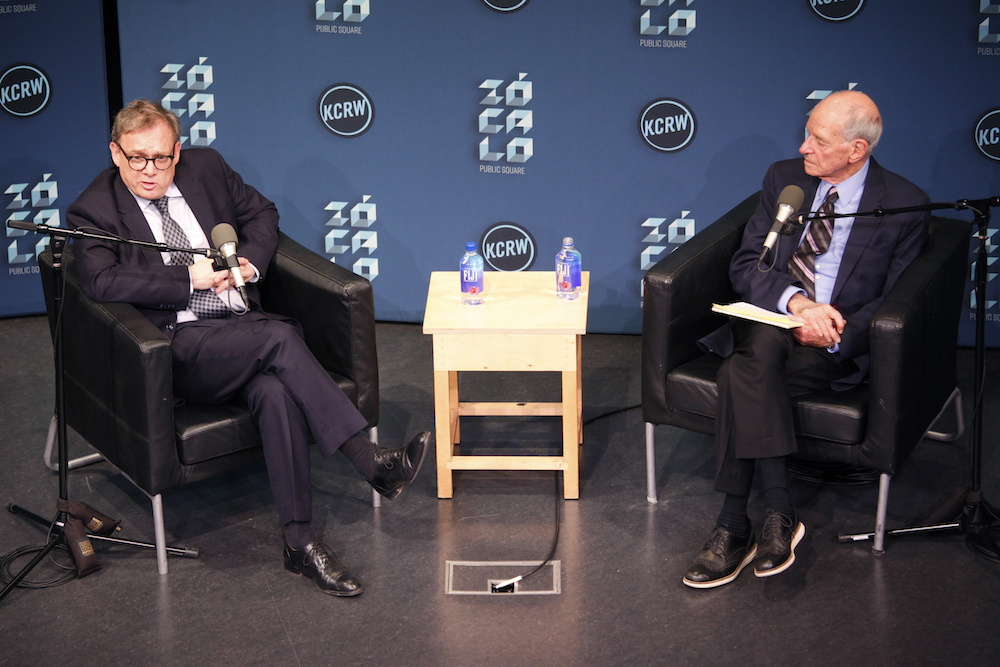

Photo by Aaron Salcido.

The United States enjoys a special place atop the global economic heap, driven in large by Americans’ willingness to embrace change—even when it hurts.

But the country’s remarkable run could be stymied if businesses can’t figure out ways to stoke productivity anew, said The Economist political editor Adrian Wooldridge during “How Has America Survived Two Centuries of Capitalism?” a Zócalo/KCRW “Critical Thinking with Warren Olney” event at the National Center for the Preservation of Democracy in downtown Los Angeles.

Wooldridge, a historian and journalist who has worked for the The Economist in Washington and in Los Angeles, today writes the Bagehot column, which focuses on British life and politics. He’s written or co-written 10 books, including 2018’s Capitalism in America: A History, a collaboration with former Federal Reserve Chair Alan Greenspan.

Before an overflow audience, Wooldridge told Olney, host of KCRW’s “To The Point,” that he began with a “thought experiment.” What if the world’s most important people in 1690 had gathered for their own Davos and asked themselves, “Who will dominate the world?”

Back then, in the late 17th century, China would have had a good case in its favor, Wooldridge argued, as might have Turkey, Spain, and even Britain. “But nobody in this imaginary conversation would ever mention the United States. It was an afterthought … it just didn’t matter that much,” he noted.

Today it’s a different story. The U.S.’s 5 percent of the world’s population produces 25 percent of the world’s GDP. America has the most forward-looking industries and the largest concentration of great universities.

“The rise of the U.S. in the last four centuries is the most important story of the last four centuries,” Wooldridge said.

Wooldridge pointed to several factors that made this unexpected economic dominance possible. Crucially, he said, Americans are better than most at “creative destruction,” a term coined by the German economist Joseph Schumpeter in 1942 to refer to the “relentless process of shifting activity to create more productive environments … going from horse buggies to automobiles, and from iron to steel.”

It’s a difficult process, he said, but Americans have excelled at it. In their book, Wooldridge and Greenspan credit this to the sheer size of the country, which makes it easier for people to move from place to place, abandoning old systems and institutions, for maximum economic gain.

“Britain is a small country, you tend to be conservative about moving people,” Wooldridge told the Zócalo audience. “Americans are careless, they uproot. You get the Rust Belt decaying and the Sun Belt rising.”

America is also a new country, forged at a time when capitalism was on the rise. The Revolutionary War took place the year after the publication of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations, Wooldridge noted. The U.S. was not shackled by old aristocratic ideas.

America’s constitution, too, made it nimbler, preventing the rise of a “massive and interventionist state” that might get in the way of innovation.

The moderator Olney asked Wooldridge about American entrepreneurs of the late 19th century—the “Robber Barons”—who Wooldridge and Greenspan call the “Titans”.

Wooldridge said that American entrepreneurs like Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller and Henry Ford were key drivers of American success, because they had “imperialism of the soul”—a desire to create boundless business empires.

Their ascendance a century ago—and our era’s rise of Silicon Valley leaders like Steve Jobs and even Mark Zuckerberg—is uniquely American, he argued. “If you’re French you want to sit in a café. If you’re British you want land and horses. If you’re German you want to be a scholar. If you’re American, you want to be an entrepreneur.”

These Titans, of both the industrial and information ages, amassed power by forming huge corporations, which provided a competitive advantage for the U.S., Wooldridge said. There were times when the Titans’ projects caused pain for workers—driving smaller competitors out of business, eliminating jobs and depressing wages—but Americans have usually bounced back.

Whether they’ll be able to do so again may be another story, Wooldridge added. A big question is whether the U.S. can restore productivity growth that it has lost, especially in the decade since the Financial Crisis of 2008.

When Olney suggested that Wooldridge was exploring how to “Make America Great Again,” the audience laughed. But Wooldridge agreed, noting that economic “stagnation is what lies behind a lot of America’s problems,” including weak wage growth, slower company creation, and economic inactivity.

“Is America past its peak?” he asked rhetorically, and suggested that the answer is no: that it was bad economic policies, rather than bad fundamentals, that were holding back growth. “We’re in an iron cage of our own making—all we need to do is turn the key and we get out of it.”

Audience members wanted to know how better antitrust laws might promote innovation (Wooldridge said research into the matter had been launched by the Obama White House but had since been stopped), and what slavery had to do American capitalism’s triumph. His answer: plenty. Slavery is “obviously an appalling stain on America,” Wooldridge said, that created “a lot of money for a lot of people.”

The conversation shifted briefly to Europe. Olney asked: “What about Brexit? What the hell is going on?”

“I have no idea,” Wooldridge said, suggesting that if the separation from the European Union was again presented to British voters in a referendum, “it will tear the country apart. There will be riots in the street. It would be appalling for democracy.”

“But I’m in favor of it,” he wryly noted, as the least terrible option.

Asked by an audience member about France’s yellow vest protesters, Wooldridge criticized President Emmanuel Macron’s approach to worker protests as “insensitive”—and saw a lesson that applies in the U.S. and the U.K. as well.

“I think one of the big dynamics we have in the world right now is a sort of wall—a metaphorical wall—between the skilled elite and everyone else. It creates a lot of tension. We need the cognitive elite to be less arrogant and supercilious.”

And if the middle class is “hollowed out” by technology’s newest wave of innovation, he said, things could get a whole lot worse. But higher corporate taxes won’t fix that. “I don’t think it addresses the problem of productivity,” he said. “There are other things we need to do.”

Send A Letter To the Editors