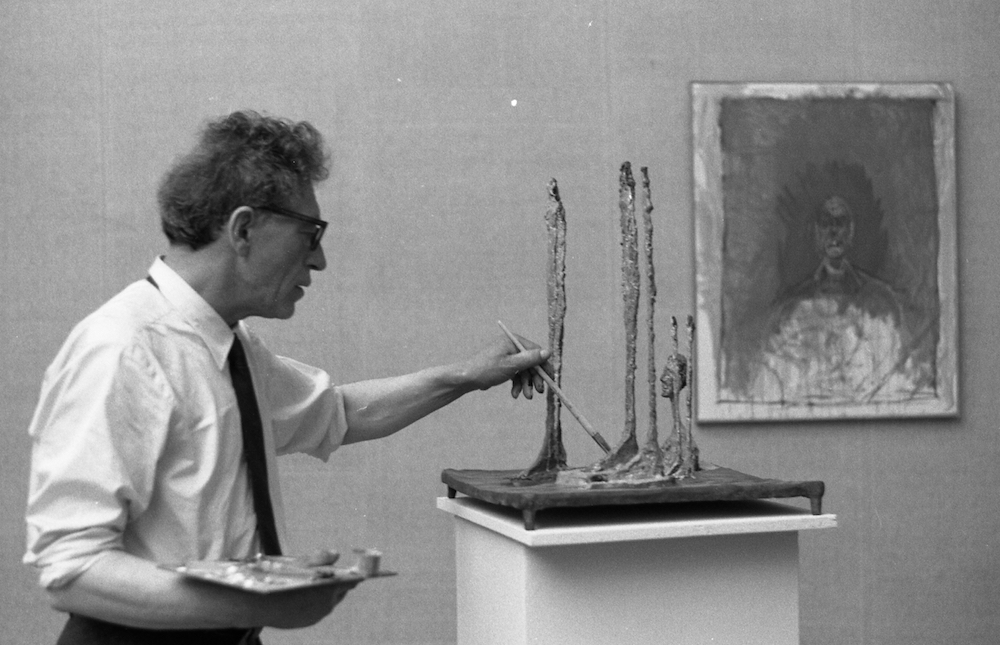

At the 31st Venice Biennale in 1962, a visitor looks at a selection of Alberto Giacometti’s work. Photo by Paolo Monti. Courtesy of the Fondo Paolo Monti, BEIC, and Wikimedia Commons.

The Swiss artist Alberto Giacometti (1901-1966) is best-known for his lean, elongated sculptures that grew progressively taller and thinner over the course of his oeuvre. His lesser-known painted portraits, like the sculpted figures, reflect his fascination with the relationship between the human body and space. And, interestingly, that space is typically painted gray. The gray worlds of the portraits are as important as the faces and bodies of Annette, Caroline, Diego, and all of the other relatives, friends, lovers, and acquaintances who appear in Giacometti’s paintings. If we give Giacometti’s grays the attention they deserve, we gain insight into the artist’s process and aesthetic, as well as the raison d’être of his art.

Critics claim the cool palette of Picasso’s blue period reflects the depression he experienced between 1901-1904. When standing in front of Picasso’s Death of Casagemas (1901), for example, we experience the weight of grief at the loss of his best friend. But for the next artist, blue can evoke the very opposite. Consider, for example, International Klein Blue, the dazzling ultramarine that defined the Yves Klein’s oeuvre. Face-to-face with the luscious electric blue of the French artist’s paintings, we want to dive in and revel in their vibrancy. The contrast between Picasso’s and Klein’s blues could not be more pronounced.

Alberto Giacometti at the 31st Venice Biennale in 1962. Photo by Paolo Monti. Courtesy of the Fondo Paolo Monti, BEIC, and Wikimedia Commons.

This variability in tone, texture, hue, and temperament can be found in different artists’ uses of the color gray. In the case of Giacometti’s portraits, the multiple uses of gray even can be found on a single canvas.

According to Giacometti, gray was the color “that I feel, that I see, that I want to reproduce,” the color that “means life itself to me.” But what was this life that he sought to reproduce, in gray?

Giacometti did not come to gray by chance. His critics and commentators like to explain the gray in which his figures are immersed on the canvas as an extension of the plaster and stone shavings that formed layers of dust over his chaotic studio. Others write about his use of gray as a disregard for, or negation of, the substance of paint. For them, gray is the background, the inconsequential space within which a human figure sits.

However, I don’t believe Giacometti pursued an aesthetic nihilism. Prior to World War II, his portraits were the same multicolored palette as those of the surrealists, expressionists, cubists, and formalists. After focusing his energy on sculpture during World War II, he returned to painting with two male busts and two standing women in 1946. These four paintings are gray. In 1947 and 1948, following a brief experimentation with a brown palette, Giacometti settled on gray for the remainder of his life. He never returned to other colors.

Critics like to explain Giacometti’s turn to gray as a response to photographs he saw of the suffering on the World War II battlefields, including images from the concentration camps.

But this explanation doesn’t match the complexity of Giacometti’s gray canvases. In an interview towards the end of his life, he discussed the reality of the streets he had been searching to recognize. He claimed that, prior to the war, reality presented itself to his eyes as a photograph, that he saw the world as if on a screen: distant, yet accessible from different perspectives. On his return to Paris, after the war, reality became unfamiliar, increasingly unstable, and eventually, unknowable. Reality on the Boulevard Montparnasse, outside Giacometti’s studio, might have been “marvelous,” but it became altogether out of reach for the artist.

Could it be that gray was the color best able to represent this feeling of a strange, unknowable reality? Certainly, the irresolution and ephemerality of the color gray seems well-suited to Giacometti’s ongoing and impossible search to represent modernity.

While siblings of the portraits can be found on the canvases of artists such as Francis Bacon, Giacometti’s figures find their closest relatives in literature. Samuel Beckett’s Vladimir and Estragon, and Hamm and Clov, are the literary cousins of Annette, Diego, and Caroline. They are all immersed in stagnant, gray worlds, always with a slither of light coming through a dirty window. Giacometti’s models recess into their gray backgrounds, as do Jean-Paul Sartre’s existentialist beings, their spiritual kin. The unidentifiable heads of Diego, Annette, Caroline and others are filled with an existentialist “nothingness” that defines their intrinsic lack of human self-identity. Indeed, Giacometti turns to gray to capture the fleeting moments as Sartrean-like human beings move along a path to ultimate disappearance.

Giacometti’s canvases also capture the myriad possibilities of existentialism in their materiality. Giacometti’s gray is tinged with purples and greens; it is, at times, steely blue, and at others, muddy brown. It can be highlighted in red or white, washed in rich earth tones, or, in a painting such as Dark Head (1959), gray is almost black. Giacometti’s gray not only opens itself to all other colors, but it also covers the spectrum from light to dark, and white to black. In the portrait, Diego (1958), gray is light itself, shining around the head of Giacometti’s brother, illuminating the shape of his nose. Gray often moves from ice cold to warm and sunny on a Giacometti canvas. As it oscillates between dichotomies, gray never sits still, bringing life to the figures and the backgrounds against which they are painted. Characteristic of both Giacometti’s conception of humanity after Sartre and the color itself, the rainbow of grays on Giacometti’s canvases are vibrant and always in process. They are neither—and both—figure and ground, representation and abstraction, perpetually in the process of becoming, often taking shape as what they are not.

In keeping with this colorful vibrancy, when we stand before them, the paintings come alive, we see figures as people with personalities given to them by their luminous gray faces. Giacometti’s figures have few individual characteristics; their only expression is in the variant gray tones of their bodies and faces, highlighted by the gray brushstrokes that surround them. True to the modernist challenge to classical portraiture, these works have nothing to do with capturing an individual’s identity or soul. They are about the perception of a body and face, distorted by its posture, in space. Like their sculpted siblings, the portraits are figures in which we identify the human. But, in the end, they are no more than manipulations of an anonymous, gray medium.

Giacometti’s tall, slender figures might be in motion, but they are trapped inside the frame. They are like their maker, who is also stuck on an idea, obsessively working and reworking their bodies until he tears their canvases. The worn, gray canvases bring out the substance of the material of painting, and simultaneously, expose what might be seen as their creator’s internal frustrations. The figures, in frames within frames within frames, are at the vanishing point of a mise-en-abîme of incarceration, sometimes about to fall out of the frame. They never succeed in freeing themselves fully from entrapment in their gray world. Together with their artist, they represent the curse of modern existence, mired in gray. In time, however, the portraits—like Beckett’s well-known characters—carry within them the promise of freedom.

The appeal of Giacometti’s portraits to the popular consciousness and the art market is inconsistent with their abstract philosophical complexity. But one thing is sure: Giacometti’s gray figures are not specific to their postwar historical moment, and neither do they belong solely to the existential crises of the 20th century.

Giacometti’s process made visible on the canvas is an expression of time, an evocation of memory and history. The figures are worked over in pencil, charcoal, or paint; rubbed out, smudged, drawn over until the canvas is torn. The “never-finishedness” of Giacometti’s portraits is evidence of his obsessive excavation of the past, as well as his belief in a future moment when resolution might occur.

When we stand before these paintings, we recognize that they are not simply unfinished. It is as though Giacometti is still working, and will continue to do so into infinity. We don’t need to hear from those who sat for him that Giacometti was a perfectionist of sorts. His models tell of endless sittings, and a continual postponement of the end. We see this exact perpetuation in the paintings themselves: Like gray, they are unfinished, ill-defined, uncertain, and still breathing possibility into the present. If Giacometti kept his sitters much longer than they anticipated, on the canvas, he never let their representations go, even when he claimed he was finished.

As much as Giacometti had a love affair with the placement of a figure in space, and an obsession for how and where, whether it was still or moving, what size and scale the figure should be, he also had a love affair with paint—with the material as opposed to the materialism of painting. That love affair gives the portraits life; in the scratches and scrawls and the swathes of gray, we see the hand of Giacometti at work, still. We meet with Giacometti on the painting to give it significance, creating an ongoing conversation between artist and viewer in the 21st century. As single-color field canvases, what can the portraits have to say about the complexity of the three-dimensional world, of the evolving patterns of human life? Everything, I would argue—just like the color in which they are painted.

Send A Letter To the Editors