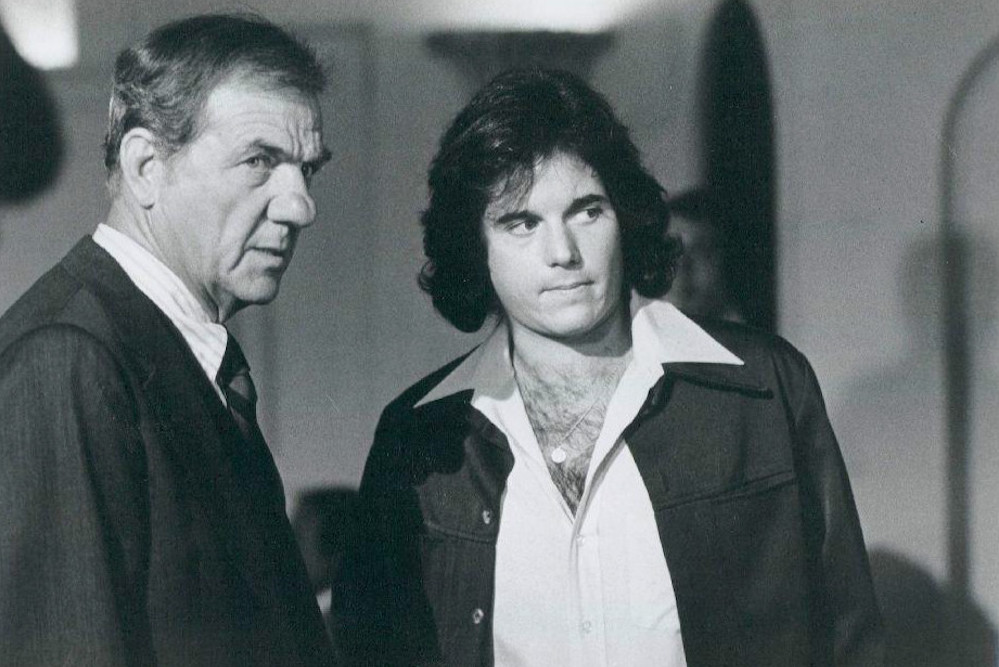

Publicity photo from the television program The Streets of San Francisco picturing Karl Malden and Desi Arnaz, Jr. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Canada’s motion picture industry earned the nickname “Hollywood North” because the country so often serves as a center of location production for American films. But in the early 1970s, this term referred to San Francisco and even headlined a series of newspaper columns covering the boom in Hollywood production in the city.

After the success of the 1968 Steve McQueen film Bullitt, which was set in San Francisco, dozens of feature films, TV movies, and television series were shot on location there. Mayor Joseph Alioto, a former attorney to movie moguls Samuel Goldwyn and Walt Disney, wooed Hollywood producers and trumpeted over $10 million in annual revenue from location shooting.

But he soon faced staunch opposition from famed San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen, the loudest voice among residents who bristled at the invasion of movie crews from rival Los Angeles. At stake were not only traffic and parking problems, but also San Francisco’s cherished image.

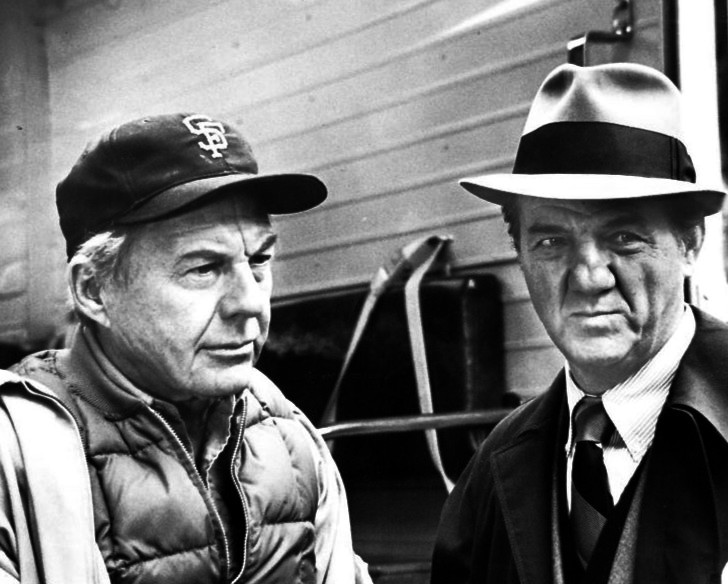

In Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry films and the popular TV series The Streets of San Francisco, Hollywood frequently depicted the city as a dangerous cesspool. Alioto sold Hollywood production as a form of tourist promotion for the city, but San Franciscans soon rallied against producers who took advantage of their hospitality only to slander the city on-screen.

As the Downtown Association of San Francisco put it, “If moviemakers persist in giving the impression that San Francisco is a crime-ridden city where police chases are an everyday occurrence, let them make their movies somewhere else.”

Despite its proximity to Los Angeles, San Francisco had only sporadically served as a location for Hollywood filmmakers in the 1950s and early 1960s. This changed late in the decade when location shooting became the dominant production method, as films like Bonnie and Clyde and Easy Rider took off while massive back lot productions like Camelot and Hello, Dolly! flopped.

Hollywood’s shift to youth-oriented films shot on location also corresponded with San Francisco’s Summer of Love. Which produced its own wave of media attention for producers to chase. Bullitt and another film, Petulia, both released in 1968, were the first commercial features shot entirely in San Francisco since the silent era, and their productions became the talk of the town as prominent socialites scored roles as extras. Bullitt soared at the box office, while reinventing the police genre and the car chase.

The first sign of disenchantment with Hollywood filmmaking stemmed from one of the most innocuous films of the era, What’s Up, Doc?, a throwback to screwball comedies of the 1930s. While shooting a car-chase finale in November 1971, filmmakers took few precautions and chipped the steps at Alta Plaza Park. This was no laughing matter for residents of the tony Pacific Heights neighborhood, as conveyed by the local headline, “Outrage at Alta Plaza.” The incident prompted the board of supervisors to consider greater scrutiny of the growing number of film productions in town.

Caen railed against “the chutzpah of these Hollywood invaders,” framing location shooting not as a local practice but as an encroachment of Los Angeles industry on San Francisco. Then he went a step further, directly tying the carelessness of filmmakers on location to their disregard in representing the city, particularly with the police genre. Figures like McMillan, Rock Hudson’s police commissioner in the television series, McMillan and Wife, were largely incompetent, but Dirty Harry was “a brute of a cop,” and other detective films like The Organization didn’t help the city’s image either.

Alioto worked to contain this early bout of negative publicity, which extended to the pages of Variety. He took the stage at the San Francisco premiere of Dirty Harry in December to assure filmmakers that, “We’ll continue to make pictures in San Francisco, and we’re not going to worry about a couple of chipped steps in Alta Plaza.” He soon put together a film committee, led by a local casting director, which conferred with local Screen Actors Guild and International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees groups working to better organize and streamline production in the city.

But Alioto stood firmly on the side of Hollywood and remained personally invested in filmmaking. He courted producers in Los Angeles, and often met with visiting filmmakers in person. Deputy Mayor John DeLuca helped secure locations for major productions. This embrace of Hollywood made him vulnerable to more direct attacks by Caen.

The San Francisco shooting boom intensified in 1972 when The Streets of San Francisco became the first weekly network series filmed extensively in the city since The Lineup in the 1950s. In 1973, three of the six features shooting in town were police films, and a fourth was a mafia picture. Violence dominated the city’s screen presence, ranging from a machine-gun massacre on a bus in The Laughing Policeman to “a sniper spraying bullets around campus” for an episode of Streets.

Publicity photo picturing David Wayne and Karl Malden from The Streets of San Francisco. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

But, once again, it was a comedy, albeit a police comedy, that drew public outcry. Freebie and the Bean featured a pair of cops, who “were hopelessly inept or corrupt,” according to Police Sergeant Bill McCarthy, who oversaw filmmaking in the city. The police department, which was responsible for safety and security during location shoots, refused to endorse the San Francisco setting. They withheld official badges and decals for the movie detectives, and all references to the city had to be struck from the script. (Of course, any viewer with a basic knowledge of San Francisco could identify the city in the background.)

Fatefully, the script also called for a spectacular car chase (a staple of police films following Bullitt and The French Connection) in which a car would fall from the lower deck of the Embarcadero Freeway. Working on a tight schedule and further delayed by November rains, filmmakers convinced the Department of Public Works to make an ill-advised decision, closing off the Stockton Street Tunnel during morning rush hour.

Caen pulled no punches, opening his column by noting the “honest taxpayers” who were forced to be late for work. He mentioned another incident where ten wrecked cars parked at one location blocked residents from pulling out of their parking spaces. He added the following exchange:

Fumed one irate woman, “who needs these people, anyway?”

Cop: “Alioto”

In a short, pithy column, Caen bluntly suggested that the regular citizens of San Francisco were the ones paying for Alioto’s movie aspirations. Supervisor Dianne Feinstein, the future mayor and U.S. senator, joined the fray, suggesting new legislation to set rules on location filmmaking. Supervisor Dorothy von Beroldingen threatened to hold public hearings on location shooting. The film committee and labor leaders managed to convince the board not to proceed any further, but the days of easy cooperation were over.

San Francisco’s appeal for filmmakers had largely rested on that cooperation, in combination with its unique, scenic cityscape. By 1975, a glut of police films had all but exhausted its novelty as a location. Meanwhile, public enthusiasm waned and logistical problems multiplied as a small, densely populated city struggled to accommodate so many production crews. Following the blockbuster The Towering Inferno and Francis Ford Coppola’s critically acclaimed The Conversation, filmmaking in the city declined through the second half of the 1970s. As generous incentives flooded in from other regions eager to attract filmmakers, San Francisco no longer had to worry about Hollywood invaders.

In the end, the most powerful handgun in the world failed to put a dent in San Francisco’s reputation. The postcard image survived the harrowing depictions of Dirty Harry, its sequels, and its many imitators. The city moved on, and so did the movies.

San Francisco’s production boom preceded the aggressive, international competition for location production that has defined Hollywood filmmaking ever since. Places that succeed, like Canada or Louisiana, still weigh the cost versus the benefit, although largely in financial terms.

San Francisco raised a rather different question about Hollywood production: What is at stake in the way that movies portray a given place, and are filmmakers accountable for that depiction?

Send A Letter To the Editors