Illustration by Be Boggs.

A worker comes to Beijing, to Communist Party headquarters, and asks to see Chairman Mao.

A soldier stops him. “You can’t see Mao,” he says. “He’s dead.”

The worker returns the next day, and again asks for Mao. The same soldier turns him away: “You can’t see him. He’s dead.”

The third day, the worker returns, and insists: “I must see Chairman Mao.”

The soldier loses his temper. “I told you yesterday, and the day before that. Chairman Mao is dead. Dead! Dead! Dead!”

“I know,” says the worker, with a smile. “I just love hearing you say it.”

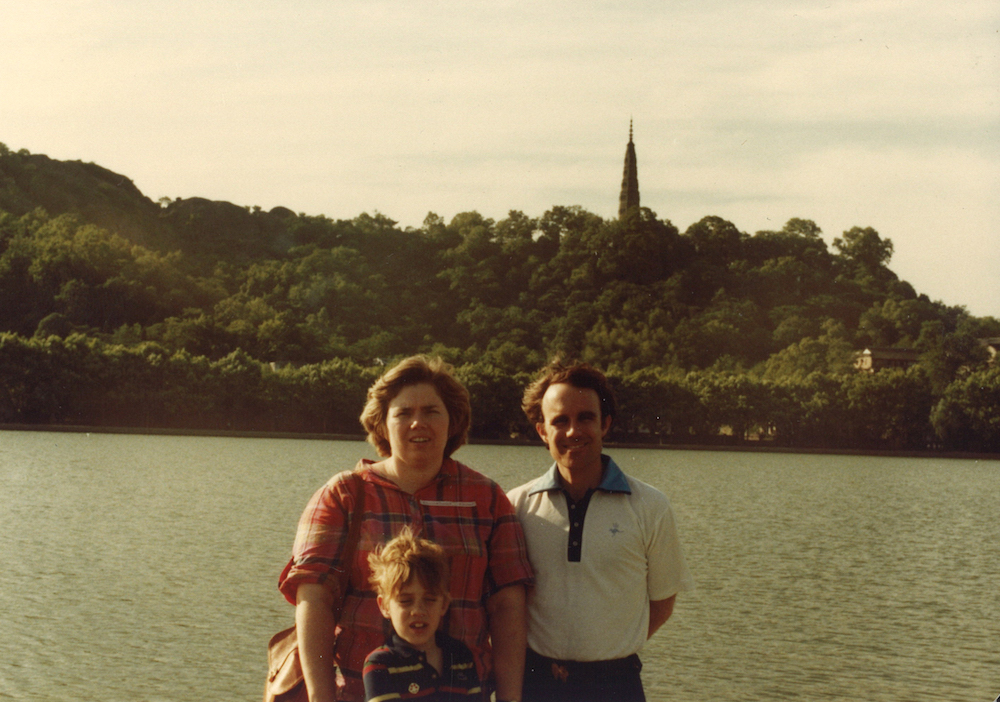

The author, seen here at age 5 in Hong Kong, where he and his family lived until abruptly moving to Beijing, after the normalization of U.S.-China relations. Courtesy of the Mathews family.

That is the first joke I remember learning. I was 6 years old when I committed it to memory and started retelling it.

You may say that a small child telling a joke like that is “not normal.” Then again, we’re seeing and hearing a lot these days that is “not normal.” It’s what we say when we see slippage in our democracies, when authoritarian leaders violate norms.

But that joke was more than normal for Joe Mathews, age 6. In fact, it was normalization.

From ages 5 to 7, I was a pint-sized participant in the creation of the modern relationship between the two most important nations on earth.

At the end of 1978, Jimmy Carter and Deng Xiaoping announced what was called normalization—the re-establishment of diplomatic relations between the United States and China, after three decades of estrangement following the 1949 Communist revolution.

Normalization immediately opened up China to Americans.

So early in 1979, not long after Deng mounted a tour of the U.S. to introduce himself, I moved to Beijing, arriving on a plane with many American diplomats and their families. I had no official status. But I was the son of American journalists, Jay Mathews of The Washington Post and Linda Mathews of the Los Angeles Times, who were two of the first four U.S. newspaper reporters given visas to live and report in China.

It has been 40 years now since that fateful spring that put China, the U.S., and the world on a different path. The experience has never left me. Beijing is the first city I knew intimately, at least as well as a child can. The Chinese capital, during the years of 1979 and 1980, is where I first became aware of the outside world. And my time there left lasting and powerful impressions—about history, about hotels, about childhood, and especially about the real meanings of democracy, tyranny, and resistance.

The author’s parents, competing newspaper journalists, took him on assignments around China. This photo is from one such trip in 1979. Courtesy of the Mathews family.

Mine is a California family, tracing our heritage to Scotland and Ireland, but for nearly a century the joke has been that we are secretly Chinese. In the 1920s, my great-grandfather, the Naval Commander Raymond Corcoran, moved his wife and children, including my paternal grandmother, to the small Shandong Peninsula seaport of Chefoo (now Yantai), where he was posted. It was another delicate moment of transition in the history of colonization and foreign influence in China; the Germans were moving out, and the Japanese were moving in. So the Americans decided to step up their naval presence.

The Corcorans loved the place, in no small part because the Chinese treated them so well. As Americans, they were seen as a better class of barbarians—much nicer than the British and Japanese imperialists who had humiliated China in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

And so my grandmother and her siblings would eventually fill their California homes with Chinese antiques and stories of the Chinese people they had known, whom they often praised for their ingenuity at surviving poverty and China’s unenlightened rulers.

These family stories deeply influenced my father, who studied Mandarin and Chinese history in college, and then lobbied his editors at The Washington Post to send him to East Asia. In 1976, when I was 3, we moved to Hong Kong, where my mother worked first at the Asian Wall Street Journal and then at the L.A. Times (Yes, my parents competed against each other on the same beat—and yes, they are still married to each other, though that is another story).

In Hong Kong, I went to an American-run Montessori school, dodged the wild dogs in my neighborhood of Repulse Bay, and welcomed a baby brother, Peter.

But mostly we waited for normalization, which would open China to us. Nixon had gone to China in 1972, but turmoil in Chinese politics (including Mao’s death in 1976) and American politics (including Watergate) meant that the effort to normalize relations stalled. It wasn’t until the second half of 1978, when Deng rose to power, that the final talks necessary to reestablish diplomatic relations began. In a matter of months the U.S. agreed to Chinese demands that it abandon diplomatic relations with Taiwan, and the talks concluded quickly.

So quickly, in fact, that when we got permission to move, we left for Beijing before we’d found a place to live or work. So, in 1979, my parents made a highly consequential decision: to move our young family of four into a 15th floor suite in the Beijing Hotel.

There is no hotel quite like it. The Beijing Hotel was the city’s leading spot for international visitors. First opened in 1915, it was really two buildings—a modern tower with 17 floors of rooms, connected to an older wing, used mostly for events, with traditional Chinese lobbies and decorations.

The hotel was in the very center of the political universe, on the Avenue of Eternal Peace, next to the Forbidden City, and a short walk from Beijing’s world-famous monuments. From the window of our room, I could peer into Tiananmen Square and see the Great Hall of the People, from which the Communists ruled China.

My parents sought other housing in Beijing, but never found it. So the hotel—specifically Room 1532—became our home for the next two years. My parents also worked in the hotel, renting other rooms as their offices. They sometimes complained about raising two young children in a hotel, but my brother and I learned to appreciate the place—and rule it.

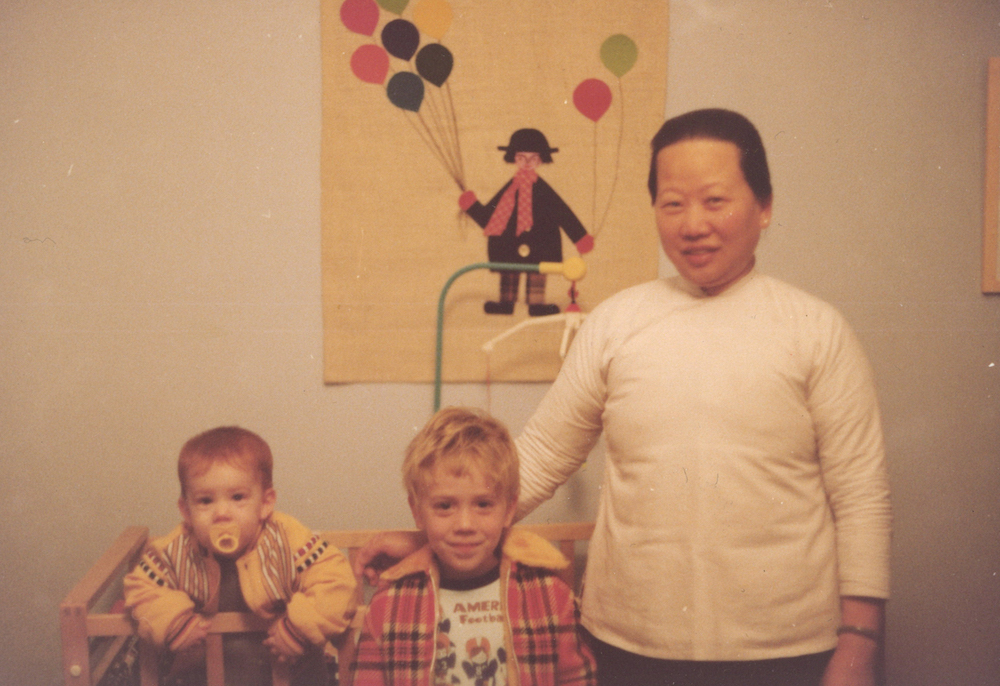

Lau Lin (right), a Chinese amah, or little mother, took care of the author (center) and his little brother in Hong Kong and then moved with the family to Beijing. Courtesy of the Mathews family.

In Kay Thompson’s classic children’s story, Eloise, a 6-year-old girl lives in The Plaza, the famed hotel on New York’s Central Park, and has the run of the place. She writes on the walls, wanders into strangers’ weddings, and tussles with the housekeeping staff, all while being chased by her English nanny.

My life in the Beijing Hotel was not so different than that.

The hotel had a very professional staff, and rules of comportment that they often recited to me. But I had just turned 6, and didn’t have time for rules.

So I rode my bicycle through the hotel halls, into the lobby, and all over the hotel’s older wing, despite many warnings to stop. My little brother sometimes joined me on his tricycle. We explored every stairwell and closet, raced on the elevators, attended events to which we were not invited, and commandeered empty meeting rooms and the hotel’s small pool hall for our games. We had too much energy to be controlled or confined for long, so the hotel staff—our uncles and aunties, as we called them—sought to pacify us, teaching us Chinese songs, playing with our Matchbox cars, and giving us 6-ounce cans of Coca-Cola (the tiny size was the only one available) or bottles of orange Chinese soda pop. Of course, the sugar only made us more energetic.

We may have been rowdy, but we were not a total nuisance. The hotel was full of important Americans traveling to China to check out new avenues of business. And I served a vital role as unofficial greeter, helping guests find their rooms and pointing the way to local attractions. Many of these early visitors to the Beijing Hotel were U.S. scientists, since Deng’s new Chinese administration had prioritized scientific and academic exchanges. I remember getting lessons in the lobby about black holes and supernovas from visiting American astronomers.

Our policing of the hotel also led to entanglements with American politicians, who raced to Beijing to build connections and help their donors pursue business opportunities. One day, my brother and I were racing our bikes down a hotel corridor when we sped into a large conference room. Peter collided with the leg of a man, who let out a loud “ouch” and fell onto the floor in pain. Our father was called to the scene, and we were made to apologize to the man, who introduced himself as Ed Koch, the mayor of Eloise’s hometown.

Technically, we were not unsupervised. In Hong Kong, my parents had hired Lau Lin, a local amah (the term means little mother), to cook, clean our apartment, and take care of us, and she bravely agreed to accompany us to Beijing. But Ah-Lin, as we called her, wasn’t always able to keep up with our hotel adventures.

She did focus on making sure we got fed—she felt I was too skinny (“Joe has no bottom,” she would complain, in English and her native Cantonese). When she wasn’t able to prepare food in the room (since it was a violation of hotel rules), she made sure we made frequent visits to the hotel dining room. The dining room was split—with Western-style meals served on one side, and Chinese food on another. We patronized both, and soon grew sick of the limited menus at each. I decided not to suffer in silence.

Then, as now, China was a country that suppressed free speech and dissent. But the authorities had foolishly left an opening: the guest book at the Beijing Hotel dining room. For most guests, it was a place to sign your name and let people know where you were from, but I seized it as a platform. Writing in block letters, I tore into the taste and warmth of the food, and the speed of the service, with a direct and undiplomatic American style. I critiqued nearly every meal in English, and a hotel staffer translated my comments into Chinese.

I got noticed. “Who is Joe Mathews?” asked one fellow diner and commenter. “This is rude,” commented another. Hotel management questioned my parents, who tried to stop me. But they had stories to file, and so I persisted. And I got results. Staffers started making dishes for me that were off the menu. They asked my opinion on changes. Not that it stopped me from criticizing. Eventually, the book was removed, and a 6-year-old future journalist learned his first lesson about democratic expression right there, in the heart of a communist dictatorship.

It would not be the last lesson.

The blond author and his redheaded brother were celebrities in central Beijing, where they used every kind of transportation to go where they pleased. Courtesy of the Mathews family.

The hotel was only one piece of my education. The streets of Beijing were quite another.

With Ah-Lin or my parents giving chase, I rode my bike all around our neighborhood, joining the thousands of Chinese on bikes (there were still relatively few cars). Before long, the capital’s center, both ancient and modern, felt utterly familiar.

I flew my kite in Tiananmen Square. My brother and I explored every inch of the nearby hutongs—the traditional alley-centered neighborhoods—and threw balls and toys against the walls of the Forbidden City. We joined the crowds lining up to visit the mausoleum that displayed Mao’s body. (“Peasant under glass,” was one expat joke I soon adopted.)

And our local playground was at the Temple of Heaven, constructed by the Yongle Emperor between 1406 and 1420. There I couldn’t help but notice the young and amorous local couples, who spent long afternoons displaying their affections publicly. What I came to understand at that playground has allowed me to brag ever since that I first learned about sex at the Temple of Heaven.

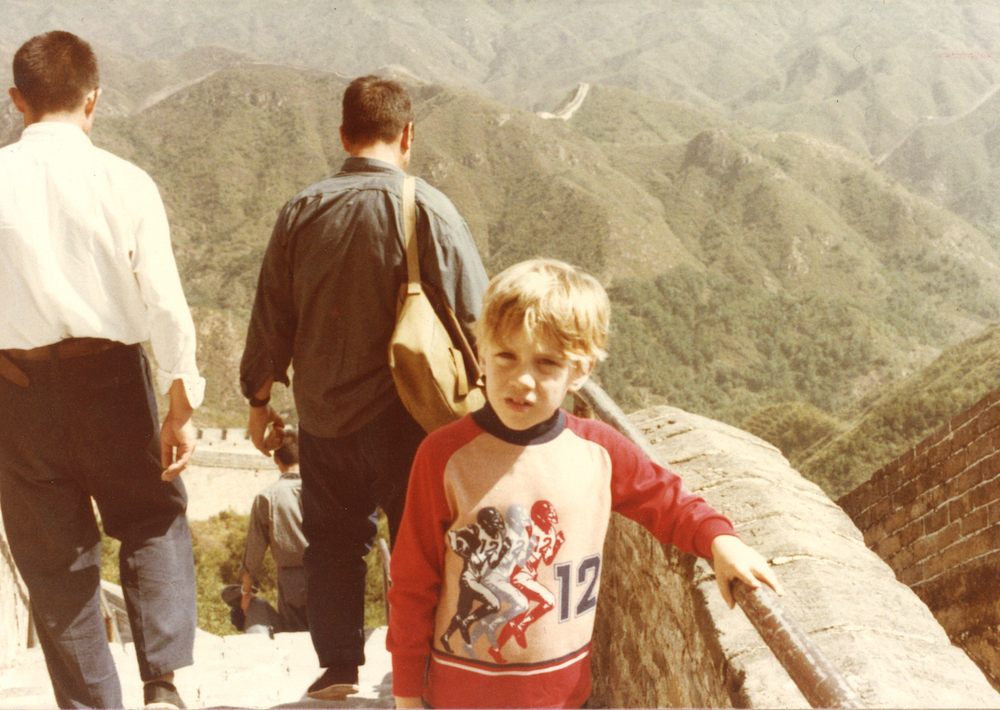

My brother and I were constantly approached by regular Chinese people. Some asked to touch our hair—I was very blonde at that age, and my brother had hair so red that it nearly matched the flag of the People’s Republic. And while Americans remember the “ping-pong” diplomacy that paved the way for Nixon’s 1972 visit to China, I practiced Wiffle ball diplomacy. My dad and I held endless games with a plastic ball and plastic bat, sometimes out at the Ming Tombs, the mausoleums that house Chinese emperors from the 15th and 16th centuries. When we played Wiffle ball in the hotel parking lot along the Avenue of Eternal Peace, hundreds of onlookers would watch, sometimes retrieving foul balls and even taking turns at bat.

Beijingers were nice to small American children, and I identified closely enough with the Chinese worldview that I made drawings of Soviet planes and rockets attacking the Great Wall, and being heroically fought off by Chinese on horseback. Deng’s anti-Soviet propaganda had thoroughly penetrated my consciousness; China fought a brief war with the Soviet-backed regime in Vietnam for less than a month in 1979.

But it wasn’t hard to find anger and conflict in the streets of the city. Fights were common. And arguments were frequent, especially in Beijing’s black markets, where Ah-Lin took me on shopping excursions. So many conversations ended in conflict, with one person declaring “I won’t stand for it” or “Wǒ bù huì zhīchí de,” that I started using the phrase myself.

Even a 6-year-old could see the link between people’s anger and their fear of authorities. So while my parents navigated China diplomatically, and my brother learned the language and customs at his Chinese government preschool, I fought back.

I refused to obey the commands of the omnipresent Chinese soldiers and police when they told me I couldn’t go here or there. I once got into trouble for banging my bicycle into the shin of a soldier who refused to let me back into the hotel. Soon, I was an unwavering opponent of tyranny, in all forms.

At my school, a converted garage at the U.S. Embassy, which I attended with 14 kids of American diplomats, I argued bitterly with the authoritarian principal. “Joe is the most insolent child I have ever known,” she wrote in a note to my parents. When they showed it to me, I replied that she too was pretty insolent—“whatever that means.”

As it turned out, I wasn’t the only person in Beijing willing to challenge dictators.

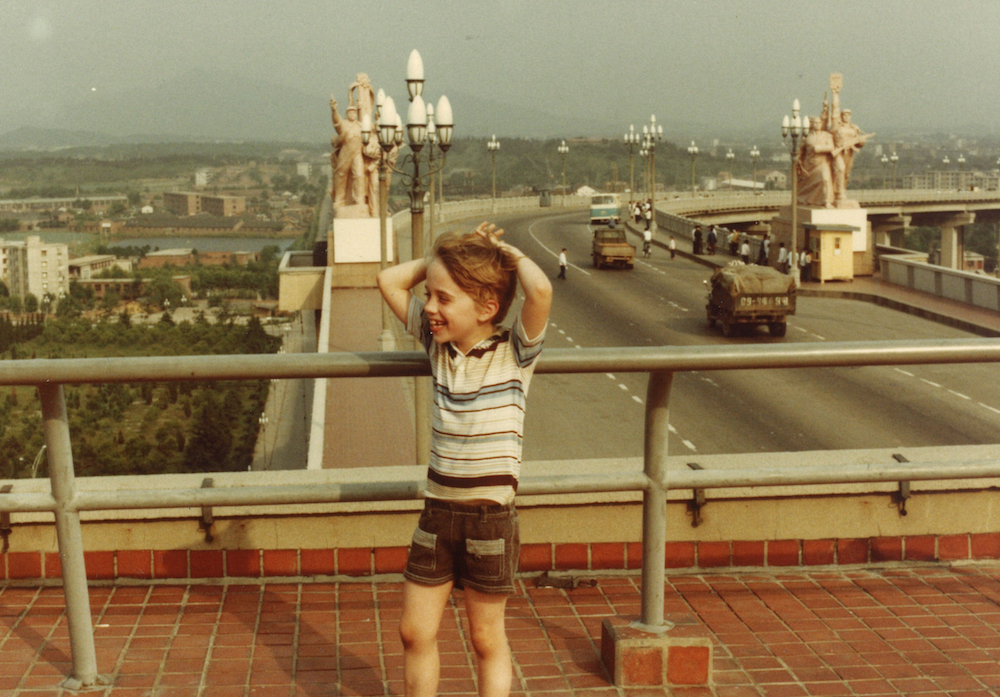

The author, age 6, in Nanjing at the Yangtze River Bridge. Courtesy of the Mathews family.

As they traveled the country reporting stories, my parents often took me along. I loved the lake in Hangzhou, a historical center of Chinese art and poetry, and the Yangtze River in Nanjing, perhaps best known to Westerners for Japanese atrocities in the 1930s. We vacationed in Beidaihe, the seaside resort favored by China’s leaders. And my dad even took me by train to Yantai, where we looked for the places where my grandmother had lived as a small child.

Sometimes, my parents used me as a decoy, hoping to avoid the Chinese government surveillance that was a fact of life. Drivers and translators who nominally worked for my parents were expected to report back to the government about their activities. So, Mom and Dad would announce they were taking me for a family outing, and instead we would visit a dissident.

I remember in particular a man named Xu Wenli, a light-fixture repairman who was publishing a pro-democracy magazine called the April 5th Forum. He had a 7-year-old daughter, Xingxing, who I liked to play with. Xu was a patriot who wanted his country to succeed. He was also cautious, and he never attacked the party’s leaders by name. But none of that saved him from being harassed and arrested by the authorities during those years.

Some of my clearest memories of Beijing involve accompanying my parents on their many visits to Democracy Wall. In 1978, at a street corner not far from the Beijing Hotel, citizens had commandeered a long wall to post messages about what had happened to themselves or their loved ones during the Cultural Revolution.

By 1979, these messages had grown more pointed, so that they included aspirations for China and democracy. I remember spending time standing there while my parents copied down the postings on the wall in their notebooks. I didn’t understand much, but I remember thinking that democracy must be something very important if people were willing to stand out in the cold to read about it, especially when wind storms flooded the air with dust from the Gobi Desert.

One man would go even further, using the wall to take on the regime directly.

Deng Xiaoping, as he ramped up his massive campaign to modernize China, had given a speech listing “four modernizations”: science, industry, agriculture, and defense. An electrician named Wei Jingsheng took to the wall to say that Deng had made a major omission: democracy, the “fifth modernization.”

“The leaders of our nation must be informed that we want to take our destiny into our own hands. We want no more gods or emperors. No more saviors of any kind,” Wei wrote. “Democracy, freedom and happiness are the only goals of modernization. Without this fifth modernization, the four others are nothing more than a new-fangled lie.”

I remember learning about Wei from my parents, and appreciating his love of challenging authority. “Dissent may not always be pleasant to listen to, and it is inevitable that it will sometimes be misguided,” he famously said. “But it is everyone’s sovereign right. Indeed when government is seen as defective or unreasonable, criticizing it is an unshirkable duty.”

To this day, I often find myself returning to the words of the essay he posted on the Democracy Wall, the “Fifth Modernization”:

What is true democracy? Only when the people themselves choose representatives to manage affairs in accordance with their own will and interests can we speak of democracy. Furthermore, the people must have the power to replace these representatives at any time in order to prevent them from abusing their powers to suppress the people. Is this possible? The citizens of Europe and the United States enjoy just this kind of democracy and could run people like Nixon, de Gaulle … out of office when they wished … In China, however, if a person so much as comments on the now‐deceased “Great Helmsman,” or “Great Man peerless in history,” Mao Zedong, the mighty prison gates and all kinds of unimaginable misfortunes await him.

There are even “certain people” who try to tell us that the Chinese people need a dictator and if he is more dictatorial than the emperors of old, it only proves his greatness. The Chinese people don’t need democracy, they say, for unless it is a “democracy under centralized leadership,” it isn’t worth a cent. Whether you believe this or not is up to you, but there are plenty of recently vacated prison cells waiting for you if you don’t.

Wei was right. In October 1979, he was convicted of publishing counter-revolutionary statements and leaking secret information. He was sentenced to 15 years in prison (and eventually released to the United States, where he still lives).

On January 16, 1980, Deng Xiaoping demanded cancelation of the constitutional right to hang wall posters and stated that the “four great” freedoms of “speaking out freely, airing views fully, holding great debates, and writing big character posters … have never played a positive role in China.”

Trips to the Great Wall and the Ming Tombs were routine in 1979 and 1980. The author played Wiffle ball at those locations, and along Chang’an Avenue, literally the Avenue of Eternal Peace, in central Beijing. Courtesy of the Mathews family.

A place so hostile to freedom is a tough place for journalists to work. Eventually, China—and hotel living—wore on my parents and their kids. By 1981, we were back in California. Since then, we have mostly watched China from afar, though my dad did go to Beijing in 1989 to report firsthand on the massacre in the very same neighborhood where I once rode my bike and played Wiffle ball.

As an adult, I’ve visited China as a tourist, even staying in the room that was our home at the Beijing Hotel. But I’m not sure I would want to work there. The place is awesome and maddening, paradoxically demonstrating both the infinite potential and the definite limits of human imagination. How could anyone who was there at the time of normalization have imagined exactly how good and how bad things would now get?

Massive advances in economic and technological growth have pulled hundreds of millions out of poverty. Today’s Beijing is literally unrecognizable. And Yantai, which had 65,000 people when my grandmother lived there and 225,000 when I visited in 1980, is now home to more than 6.5 million.

Even less conceivable is the unprecedented technological breadth of today’s Chinese police state, and the rise of another dictatorial figure, Xi Jinping, who engages in mass purges and violates norms while fashioning himself as the new Mao.

Of course, China isn’t the only place experiencing changes that once seemed unimaginable. My own country’s wealth, and power, and technology also have grown beyond expectations. And our democratic norms have withered with a mind-boggling speed and force. American government and American businesses have fashioned a surveillance state far more intrusive than the flesh-and-blood one that spied on my parents back in 1979.

Today’s conventional wisdom is that China and the United States are competitors, two very different powers fighting over control of the world. But from where I live, in California, the two countries and their leaders seem all too much alike. Xi and Trump both embrace nationalism, xenophobia, and conspiracy theories in service of extending their power. Both offer slogans and relentless propaganda. Both bully their neighbors.

And while both men talk about dreams, both wallow in false nostalgia. Trump wants to take us back to a whiter America and build his own Great Wall, while Xi suggests reviving the Zhou dynasty, which lasted 800 years, concluding two centuries before the birth of Christ.

I can’t shake the past, either. With everything going on in America now, I find myself thinking about the China I knew as a kid. The anger and bitterness in American life today feels familiar to this onetime Beijing boy. So do the plaintive pleas for democracy, scrawled on every available surface.

And so does the citizen’s conviction that challenging tyranny is an unshirkable duty that you can’t abandon until you’re absolutely sure that the tyrant is dead, dead, dead.

Send A Letter To the Editors