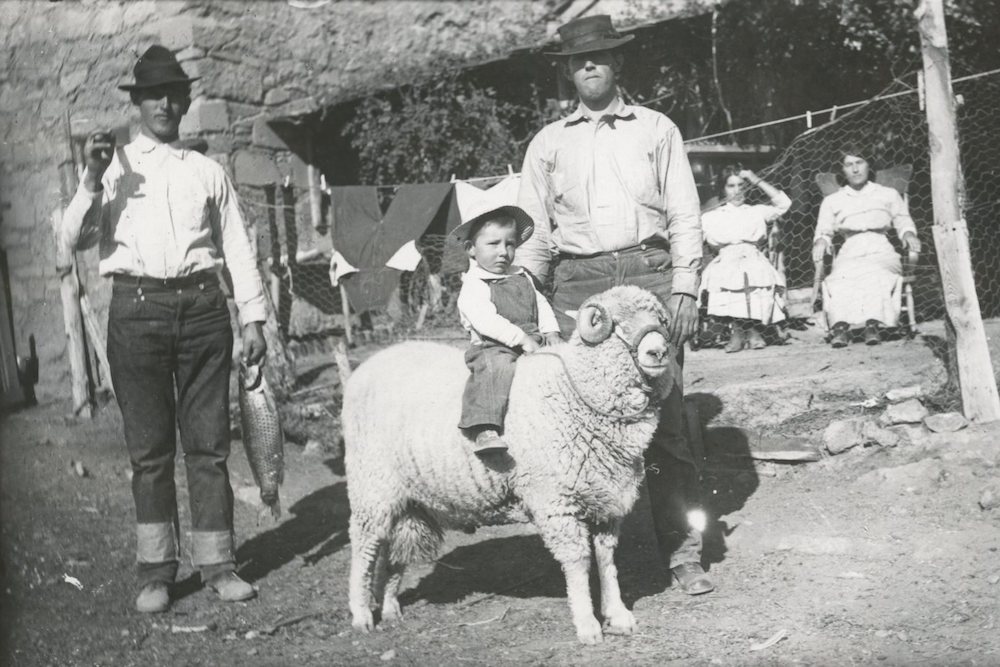

Basque residents in the Jordan Valley in Malheur County, Oregon. Courtesy of the Oregon Historical Society’s Research Library, photo by Pascual Eiguren.

One enduring myth of the American West is that people of Basque origins or ancestry came to dominate sheepherding because of the skills they brought with them from the old country.

The real story is less about sheep and more about migration, desperation—and money.

In the 1850s, some Basque families, including the Altubes and the Garats, arrived in California as its mining economy expanded. These early Basques had previously fled to South America during the problematic path of transition from the old regime to a liberal state in the early 19th century. But during the gold rush, these Basques set out again, eager to join the economic exploitation of California’s land and resources. Some stayed in the West, starting business ventures in livestock ranching and related products to feed the new state’s expanding population. Today, some Basque-Americans who inherited their immigrant fathers’ or even grandfathers’ stock businesses are still raising meat on the hoof.

Still, the original Basque immigrants were not experienced sheepherders. Perhaps some had tended a few sheep in the Basque Country, but certainly none had worked as open-range sheepherders before they immigrated to the United States. Basque immigrants took on this work because it paid relatively well—largely because it was considered undesirable—and did not require special skills or a command of the English language.

By the early 1870s, California land prices and population were increasing, and the Basque stockmen moved eastward to marginal lands in the Great Basin, which the transcontinental railroad had just connected to all the major markets. In northeastern Nevada, for example, land for grazing was still plentiful and cheap. There, in Elko County, Bernardo and Pedro Altube from Oñati, a town in the province of Gipuzkoa in Basque Country, formed the partnership called Spanish Ranch. By the late 1880s, though their numbers were relatively few, a small Basque immigrant community had created an ethnic economic niche based largely on the open-range sheep industry, paving the way for further Basque immigrants by giving them employment as ranch hands.

By the 1890s, the early Basque herders were making the pattern of the “agricultural ladder” work for them and subsequent newcomers. Basque arrivals would begin by herding as wage workers—though some were compensated in lambs. Receiving their wage in lambs enabled many to operate mixed sheep bands (of both owners’ and sheepherders’ lambs), create their own sheep operations (oftentimes forming partnerships), and purchase land and property. By the early 20th century, Basque-owned sheep operations were ubiquitous in the West.

The omnipresence of Basque herders helped create a stereotype of those immigrants as having innate skills with sheep. But it wasn’t only their abilities, but also how they fit into American concepts of racial hierarchy that contributed to this myth. By the early 20th century, Basques were often depicted by non-Basque ranchers as good sheepherders who were racially superior to other non-white ethnic groups. In September 1903, the Colorado Rocky Ford Enterprise asserted that “the class of men … in demand for herding the sheep were known as Basques or ‘Bascos’ … They naturally take to the life of solitude, as they and their ancestors have been employed in a similar occupation in the Pyrennees [sic] Mountains for many years past.” This myth, based on the false premise that Basques had been sheepherders back home, came to define Basque-Americans for many Americans.

Despite the positives of the myth, the omnipresence of Basques sparked a backlash. By the 1890s, Basque herders roaming freely on public domain lands with several thousand head of sheep were perceived by the older livestock operators as a growing menace to established ranching. They were also seen as potential environmental villains by the American Conservation Movement that would form a major aspect of Progressive reform politics in the first decade of the 20th century.

When Congress and the President moved to establish forest reserves and eventually national forests in the late 19th century, issues of rangeland governance made the presence of Basque itinerant sheepherders central to local and national debates. And those arguments turned Basques into scapegoats.

Conservationists claimed that transient sheepherders were detrimental to agricultural development because they did little to build up the land. By this argument, the Basques should not be favored at the expense of the regular occupants, large or small. Local ranch owners and the small-town business communities, which depended on the prosperity of the ranges, complained to state and federal representatives. Resentment against these transients led to the occasional roughing up of sheepherders or the killing of their dogs. And most local U.S. Forest Service officials defended the idea of keeping many Basque herders out of the national forests in favor of those who had stronger ties to the local business communities. Forest rangers, in reports to their supervisors recommending the exclusion of sheep in the national forests, typically portrayed Basques as “furtive” and selfish destroyers of the environment.

In 1910, Basque immigrant Pete Jauregui built The Star Hotel in 1910 in Elko, Nevada. Courtesy of the Northeastern Nevada Museum.

This photograph of The Star Hotel was taken in 1959. The hotel is still open today. Courtesy of Northeastern Nevada Museum.

During the years before World War I, a rising wave of anti-immigrant sentiment made acceptance and integration of the Basques even more difficult. But through the 1910s, more settled Basque communities, widely dispersed throughout the West, continued to attract further emigration of Basques. These communities, often working together, developed better collective strategies to help newcomers in the transition to living in the U.S. For example, Basque-owned boarding houses offered immigrants housing, employment, social protection, and other kinds of assistance, like health care and mail service. Such boarding houses also offered to the public some traditional foods and liquors at a reasonable price through on-site bars, paving the way for closer relations between Basques and non-Basques.

As the 20th century advanced, the reputations of sheepherding and Basque culture improved. Some old Basque boarding houses were turned into Basque restaurants, which today are among the most popular ethnic businesses in the American West. For many people, these establishments—and the myth of the Basques’ special relationship to sheep—are all that remain of a far more complex history.

Send A Letter To the Editors