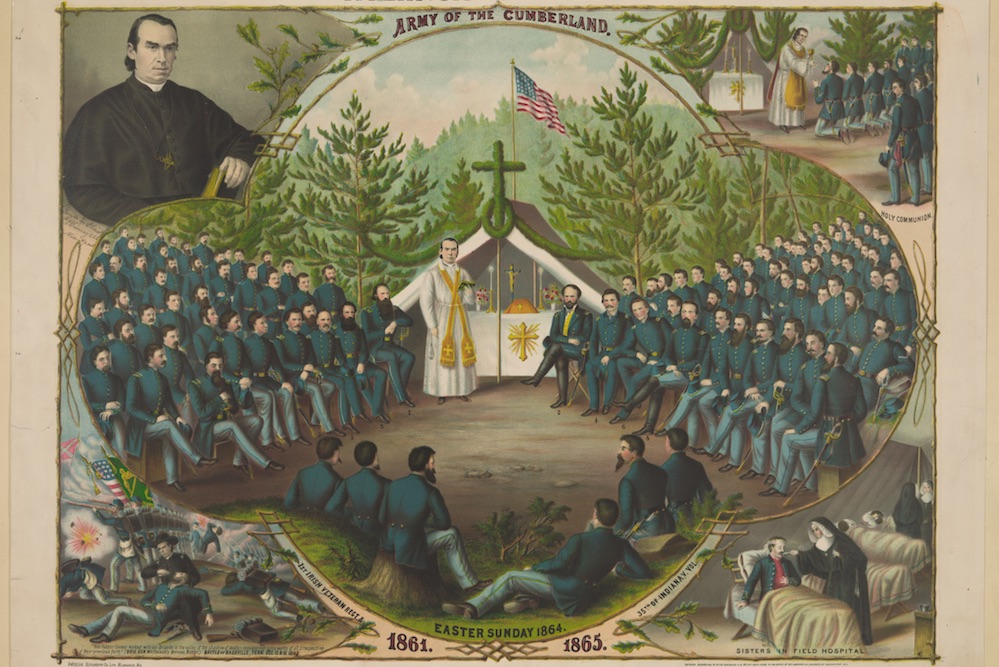

The Rev. P.P. Cooney conducted church services for Union soldiers during the Civil War’s Atlanta campaign. In hospitals and prisons throughout the war, chaplains promoted twin patriotic impulses that persist today: civil religion and religious nationalism. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Chaplain Henry S. White, of the Fifth Rhode Island Heavy Artillery, was a devout Christian—and so when he was captured by the Confederacy, he naturally led a service for his men in prison that included prayers for the U.S. government and its armies. For White’s Confederate captors, praying for the U.S. government amounted to a hostile action. One Sunday, the prison commandant, a Captain Tabb, listened in on the service and scoffed, “Well, your prayer won’t do much good,” according to Frederic Trautmann, a Union soldier who witnessed the scene.

The Civil War was a time of great discord, tearing men away from their families and routines, pitting neighbor against neighbor and countryman against countryman. But it unified Americans in at least one crucial way. As illustrated by White’s services at the Confederate prison in Macon, it forged together twin traditions that still resonate in American life today: civil religion—the celebratory, peaceful tradition that unites a chosen nation “under God” that is not linked to any specific religion—and religious nationalism, with its emphasis on blood and sacrifice as guarantees of American success.

It was during the Colonial era that civil religion took root in America. Sociologist Philip Gorski has drawn attention to its emergence in seminal documents such as John Winthrop’s “City on a Hill” speech from 1630, the Declaration of Independence, and the U.S. Constitution. All three works define a sense of this budding American civil religion. Winthrop’s speech was a jeremiad specifically intended to chasten sinful listeners, but it also emphasized God’s covenant with the Puritans and a sense that they were a chosen people. The Declaration and the Constitution suggested that what was happening in America was unique, revolutionary, and exceptional. As early as 1777, Americans were commemorating the Continental Congress’ adoption of the Declaration of Independence, as they gathered for Fourth of July celebrations.

By the 1860s, Civil War hospitals and prisons provided fruitful atmospheres for civil religion, too. Chaplains and missionaries flocked to these spaces to minister to men with ample time on their hands and a keen interest in the afterlife, encouraging spiritual development by providing religious education and leading services, prayer meetings, and funeral services. Holidays, in particular, were a time when men fostered a deep connection to the Union. Confederate soldiers demonstrated a similar devotion during fast days, held periodically throughout the war. As remembered by hospital administrator Jane Woolsey in Hospital Days: Reminiscence of a Civil War Nurse, holiday sermons during Christmas (a religious holiday) and Thanksgiving (a civic celebration), filled the air with patriotic motifs such as “Rally Round the Flag, Boys” and “My Country ‘tis of Thee”. White reported that his fellow chaplain Charles Dixon delivered a Fourth of July service that included “warm and holy petitions for the President and the country” and national songs.

One might think imprisoned soldiers would not be receptive to such warm feelings for their country, but Union soldiers reveled in any chance to celebrate the Union—led, in large part, by President Abraham Lincoln, the stalwart defender, and epitome, of Union civil religion. Loved and respected by many Union soldiers when he was alive, Lincoln was revered by them in death. Special services within general hospitals after his assassination attracted large crowds of mourners. Two thousand people met in the open air to celebrate Lincoln’s life at Fort Monroe, Virginia, on the day of the president’s funeral in April 1865.

At the same time, Civil War hospitals and prisons were fertile ground for the growth of religious nationalism, an impulse that had never been a major force in U.S. civic life before. Religious nationalism’s martial undertones resonated with soldiers facing unprecedented high casualty rates, sacrifice and tribulation—including soldiers housed in Civil War prisons. Importantly, it justified the massive scale of death in this conflict, far surpassing that of any other war American had fought to date.

Union Chaplain Charles Alfred Humphreys described the transformation from purely civil religion to civil religion merged with religious nationalism in his memoir, Field, Camp, Hospital and Prison. While imprisoned in Lynchburg, Virginia, Chaplain Humphreys preached to his fellow captives on the Sabbath, reminiscing about religion at home. But instead of hearkening to feasts and celebrations and Lincoln’s comforting equanimity, Humphreys spoke to his audience about the Babylonian Captivity of the Hebrews. He emphasized the “duty of remembering still our country’s cause and serving it by patient endurance of our sufferings—as ‘they sometimes serve who only stand and wait.’” Detained at Kinston, North Carolina, the same Henry S. White who was later to be imprisoned at Macon emphasized the “sacred flag and its noble defenders,” as well as “our personal salvation and holiness.”

These messages, clearly needed in the prison environment, affirmed the reality of suffering but noted that it could be overcome. In a sense, all worldly suffering was temporary, for a Christian hoped to reach heaven. Soldiers also viewed these ideas through a more secular lens. These men were fighting to preserve the Union and their identity as American citizens.

After the Civil War, the twin ideologies continued to expand their importance in the U.S. The post-Civil War North adhered to a civil religion tied to a strong union, while the post-war South clung to the religious nationalism of the Lost Cause. Civil War battlefields became contested through monument building by Northern and Southern groups, valorizing the soldiers on their respective sides. While the North continued to industrialize at a fast rate and the South maintained much of their pre-war agricultural focus, these dueling ideologies gained adherents in the respective sections of the reunited country. By World War I, as U.S. strength was on the rise, the two regional bents unified into a single central ideology motivated by increased militarism and imperialism. Later, with the development of nuclear weapons, religious nationalism shifted away from sacrifice toward apocalypse and sacralization of the military.

While the average American seldom thinks about it today, many present-day patriotic demonstrations—from singing “The Star-Spangled Banner” at sporting events and standing for the Pledge of Allegiance in school to calls for war to protect American interests in another region of the world—share their origins in Civil War hospitals and prisons. America has become a very different place than it was in the 1860s; but the Civil War chaplains would recognize it all.

Send A Letter To the Editors