During World War II, Axis diplomats in the U.S. were detained at luxury resorts, such as the Greenbrier Hotel in West Virginia. Courtesy of the Greenbrier.

In the 1930s, as the drumbeats of war in Europe and the Far East grew louder, Americans maintained their workaday lives and strived for business as usual—as did their employers. “At a traditionally famous hotel, the Greenbrier in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia,” read one ad in the April 1938 issue of Nation’s Business, “Mr. Loren Johnston, General Manager, wanted a letterhead as fine as the classic columns of his portico, as fresh and crisp as his table linens, as pleasing as the rhythm of his dinner hour orchestra. The paper he chose was Strathmore.”

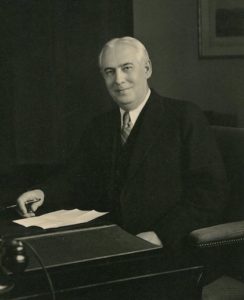

Johnston, a courtly veteran hotelier accustomed to catering to the rich and famous, might seem an unlikely choice to voice bedrock American values in dark times. But that’s exactly what he did when World War II broke out, and the U.S. government decided to house diplomats from the Axis countries of Germany, Italy, and eventually Japan at his luxurious hotel.

Thanks to the Greenbrier’s meticulous records, maintained over the last four decades by on-site historian Robert Conte, Johnston emerges as a patriot who exhorted his employees to serve America’s enemies with courtesy and respect, even when their neighbors and countrymen were vilifying them.

Loren Johnston rallied the staff of West Virginia’s Greenbrier Hotel, exhorting them to treat their diplomatic prisoners with the same consideration they’d offer any other resort guest. Courtesy of the Greenbrier.

“You may all rest assured,” he wrote his staff of several hundred shortly after the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, “that our Government has a very good reason for everything they request us to do, and it is not our privilege to question. It is our duty to serve these people for the duration of their stay in the best possible manner.” His hotel crew responded with alacrity, performing the countless behind-the-scenes jobs that guests only notice if something goes amiss. Their unstinting efforts exemplified the work so many Americans did to unite the nation in the face of crisis.

What Johnston asked his team to do was difficult because it was unpopular. For years in the U.S., a debate had raged between interventionists who wanted to confront fascist and totalitarian threats, and isolationists led by the America First Committee, who were determined to stay out of another world war. When bombs fell at Pearl Harbor in December 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared war on Japan, and days later, Germany and Italy declared war on the U.S. As a result, the isolationist argument collapsed over a matter of days, and in its stead arose another animating, if ignoble, national sentiment: hatred of a common enemy.

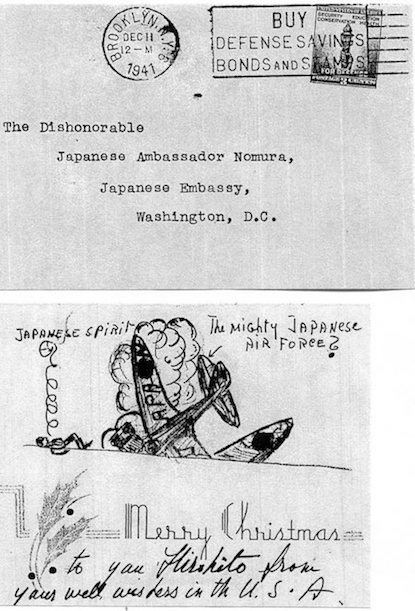

Newspapers’ vitriolic headlines, editorials, and racist caricatures of buck-toothed Japanese fanned the flames of animosity, especially against the two most reviled men in America: Ambassador Kichisaburō Nomura and Special Envoy Saburō Kurusu, who had been sitting in Secretary of State Cordell Hull’s office as the bombs rained down on Hawaii. They were two among hundreds of Axis diplomats living and working in the nation’s capital. Fearful of envoys’ ongoing communications with home, the Roosevelt administration made a controversial decision to send these foreign nationals and their families to remote luxury hotels. The primary goal of this plan was reciprocity—the hope that good treatment of enemy diplomats here would engender the same for American counterparts trapped overseas. (It did not.)

This roundup, detention and eventual repatriation of more than a thousand Axis diplomats and dependents, little remembered today, was a cause célèbre that rocked the nation and enraged many Americans. “May I ask why our government deems it necessary to pamper the delegation of Yellow Rats by housing them at one of the country’s finest winter resorts?” fumed one Washington state resident to Senator Monrad Wallgren. A railroad executive from New York wrote to Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles: “As a patriotic American for many generations, [wouldn’t] any old wooden shack be good enough? Why coddle German and Jap prisoners who are all bitter enemies of our country, and who would ruin us if they had half a chance?”

Sheltering Axis diplomats wasn’t popular among angry Americans, who flooded the Japanese Embassy with vitriolic letters after the Pearl Harbor bombing. Courtesy of the U.S. National Archives & Records Administration.

Two rural luxury hotels immediately signed on during their quiet winter off-seasons: the Homestead in Hot Springs, Virginia, tasked with housing the Japanese, and the Greenbrier in nearby West Virginia, which took in the Germans and Italians. Fay Ingalls, owner of the Homestead, recalled the government’s request as more “in the nature of a command”—but Johnston responded more enthusiastically, writing to a friend that “we immediately enlisted.”

By the end of December, the initial contingents of diplomats arrived at each hotel, infuriating many local residents. When White Sulphur residents cried foul, Mayor William Perry, who also served as the Greenbrier’s purchasing agent, addressed a town meeting. “We, and I speak for every person in our town, are happy to have this privilege of doing our part during the war crisis,” he insisted. “Our whole tradition here in White Sulphur Springs is one of patriotism and support of our government.” Outraged residents of nearby Lewisburg also demanded a public meeting, where they heard from Charlie Spruks, a top State Department official in its protocol division. Spruks expounded on the noble goal of reciprocity but changed few minds. “Over at White Sulphur Springs,” wrote the Charleston Gazette, “the regular clientele has been chased out so that the delicate bluebloods representing Hitler’s superior Nordics will not have to breathe the same air of plebian Americans whose habits of paying their bills and cussing an enemy to his face show plainly they are not born to the aristocracy. Here is a West Virginia resort … given over to as deceitful and rascally a flock of hired bravos as ever worked the doublecross.”

A native Vermonter, 64-year-old Johnston had managed high-end properties in Vermont, Pennsylvania, and Florida. At the latter he once refereed a four-man golf match that included John D. Rockefeller, Sr., then the world’s wealthiest man. Johnston was also an amateur photographer who donated all proceeds from his exhibitions to local charities. Though his establishments attracted an upscale clientele the heavyset, genial Johnston, who joined the Greenbrier in 1928, was an empathetic boss much beloved by his staff. Pronouncements from on high, no matter how well meaning, only have effect if people listen—and Johnston’s staffers took his words to heart.

Every day, bookkeepers and housekeepers, movie operators and telephone operators, painters and waiters, musicians and masseurs and others performed admirably under difficult conditions. To pass the time diplomatic guests dined on fine food, shopped, swam, and played table tennis and board games. But the diplomatic families quickly grew bored—and some took special pleasure in complaining.

In February 1942, when Italian diplomat Alberto Rossi Longhi criticized the hotel’s cleanliness, Johnston asked its chief housekeeper, 70-year-old Mary Florentina Harrington, to respond. Having been employed by the resort for nearly three decades, she had contemplated retirement previously but had stayed on to help during the detainment. She told Johnston that Rossi Longhi “has been overheard to say that we have only one vacuum cleaner for the whole house. For my part I would not feel obligated to tell him that we have many Hoovers and four large drum vacuums.” She added that “we have tried in every way to avert any unpleasantness, anything that would cause repercussions on the other side.”

It wasn’t only employees who held their tongues. On-site federal agents did too. State Department agent John O’Hanley confirmed Harrington’s stance: “Rossi Longhi said that he had a sore throat attributed to the [dirty] rugs in the lobby but, on my word of honor, I saw him walking around in all the rain that day with one of his boys. I didn’t mention this to him, of course.”

At the outbreak of World War II, the U.S. Government detained Axis diplomats at luxury resorts, hoping to limit their outside contacts. These German detainees stayed at the Greenbrier in West Virginia. Courtesy of the Greenbrier.

Just as Mussolini forever chafed under Hitler’s boot, so too did the Italians at the Greenbrier resent the arrogant Germans—and in the spring, the State Department shipped the Italians to the Grove Park Inn in Asheville, North Carolina, replacing them with the Japanese so the Homestead could reopen to the public for its spring season. But the Germans and the Japanese got along even worse than the Germans and Italians had, and the move re-inflamed local residents. Johnston got wind of a special town council meeting and immediately tipped off O’Hanley: “I very clearly stated to those who have approached me that under no circumstances is the Greenbrier to be included in any protest or any comment that may be considered or made public.” Though the council soon issued a resolution that “doth hereby protest most vigorously to the Japanese Enemy Aliens being interned in or near said Town,” the die was cast.

Once again, Johnston privately offered eloquent encouragement to his staff:

A great many millions of people are serving their governments under greater hardships than any of us have known up to this time, so I bespeak your continued loyalty and assure you of my keen appreciation … It must be remembered that this country is in a grievous war which will affect each and every one of us no matter what our work may be, and in order that we may properly perform our service we must be polite and patient, helpful to each other, and do our full duty.

The harmonious relationship between labor and management—and the cordial relations between hotel workers and their guests that it engendered—didn’t go unnoticed by on-site federal agents. “The attitude of your entire personnel reflects the love and devotion they have for you, for they have followed to the letter your instructions that these various Nationals be treated as if they are your customary guests,” wrote O’Hanley, who added that his team felt the same way. “I know that each man, like myself, will be singing the praises of the Greenbrier and the hospitality of yourself long after our present guests are returned to their native lands.” The camaraderie and graciousness even seemed to rub off on other agents. “I hate Germany and Hitler with all my might,” admitted one border guard, “but working with these people, for my life, I cannot hate them!”

Behind the scenes, tedious and often tense negotiations for the diplomats’ release dragged on for more than six months; it was the summer of 1942 before the diplomats finally sailed home. Japanese nationals traveled to Mozambique, where they were exchanged with Americans arriving from Japan. There, news correspondent Masuo Kato met up with an old friend, AP reporter Max Hill. After swapping stories of their respective confinements—Kato’s luxurious life at the Homestead and Greenbrier versus Hill’s mistreatment—Hill said, simply, “I am proud of my country.” America’s detainment of the Axis diplomats ranked as the gold standard, far kinder than the treatment afforded U.S. envoys abroad by the Italians, Germans and especially the Japanese, who imprisoned and tortured some journalists and businessmen.

The Germans sailed across the Atlantic to the exchange point of Lisbon. One evening, the young son of an embassy secretary entertained the group by singing a song he’d learned from the border guards at the Greenbrier: “Deep in the Heart of Texas.”

In the end, it was the hotel staffers who were most responsible for the top-notch service captives like that boy received, and the unlikely bonds it forged: Unsung Americans—men and women, black and white and brown, old and young, native and foreign born—pitched in to do the right thing at the right time. Taking direction from their boss Loren Johnston, their fight to do what was right demonstrated American willpower at its finest—the spirit and determination that propelled America to win the war.

Send A Letter To the Editors